|

Preparing

The NRO For The Future

The

NRO must constantly engage in the most advanced research, development

and acquisition efforts so that it can continue to place the latest

and best reconnaissance capabilities in orbit.

Timely, high

quality space reconnaissance based on technological innovation

is of crucial importance to both strategic and tactical decision-makers.

To provide this, the NRO must constantly engage in the most advanced

research, development and acquisition efforts so that it can continue

to place the latest and best reconnaissance capabilities in orbit.

The Commission concludes that significant actions must be taken

to enable it to do so, and that these actions should reflect those

qualities, characteristics and attributes, as summarized below,

that enabled the NRO to achieve its great past successes.

Engineering

Creativity. While new NRO systems have responded to the

desires of external customers, NRO engineers have also been

free to pursue "the art of the possible" and to develop

new technological solutions to solve intelligence problems whenever

feasible. This has allowed NRO engineers to focus on improving

system performance, rather than being limited by rigid, consensus-driven

customer requirements. Given wider latitude, they have been

more creative. Thus, the NRO is accustomed to delivering first-of-a-kind

satellites.

Performance

First. In making design choices for new NRO systems and

upgrades, superior satellite performance has been considered

more important than constraining costs. Budget constraints have

not been ignored, but sufficient funds have been made available

to the NRO to pursue promising new technologies.

End-to-End

Systems Approach. The NRO's distinctive approach has included

end-to-end development of space reconnaissance systems. While

developing a concept of operations for a future satellite system,

NRO program developers considered how, by whom and under what

conditions the system would be tasked. While determining how

raw satellite data would be transformed into a useful product,

they considered mission ground station operations. In some cases,

they actually developed TPED tools and techniques to be used

in conjunction with the new satellite system. Understanding

the entire process permitted the development of break-through

satellite systems and the capabilities required to support them.

Cradle-to-Grave

Perspective. In some cases, NRO engineers have also operated

the satellites they designed and built, thus developing unique

and important insights into possible future capabilities. Among

other things, solving on-orbit anomalies, watching and understanding

the changes in intelligence targets, and incorporating new hardware

and software upgrades have contributed to a thorough NRO understanding

of space reconnaissance systems and the targets they must attack.

Senior

Level Attention. One of the most important reasons for the

NRO's success has been the partnership between the Secretary

of Defense and the DCI, explained in further detail in this

Report, that has permitted the creation of a single vision for

space reconnaissance and allowed the NRO to operate differently

than other activities in the national security community.

From its

earliest days, the NRO collected information essential to strategic

and tactical decision-makers. Part of the DCI's contribution

to the partnership has been advocacy, on behalf of the Intelligence

Community, for crucial strategic intelligence collection that

can only be conducted from space. As the President's primary

intelligence advisor, the DCI requires substantial amounts of

such information. At the same time, the Secretary of Defense,

representing the other half of the partnership, requires NRO

information to ensure global situational awareness and battlefield

information dominance for his military commanders.

Special

Authorities. The Secretary of Defense-DCI partnership also

has provided the NRO with the authority to use extraordinary

policies and procedures to advance its efforts. Among these

are the NRO's exemption from normal DoD procurement policies,

procedures and regulations. The NRO has also been allowed to

use the DCI's special statutory procurement authorities under

Title 50 of the U.S. Code. These authorities helped provide

the foundation for the NRO's unique acquisition process and

its exceptional relationships with contractors.

Unified

Direction. The Secretary of Defense and DCI agreed to establish

a single NRO Director with a single vision based upon a single

space reconnaissance budget. Internal disagreements involving

competing demands for constrained NRO resources are settled

by one Director within one organization, based upon an understanding

that space reconnaissance is essential for the success of DoD

and the Intelligence Community.

Special

Security Protections. Until 1992, the NRO was surrounded

by a wall of secrecy. This environment kept foreign intelligence

services from gaining a comprehensive understanding of U.S.

space reconnaissance capabilities. The absence of information

on NRO spacecraft attributes, sensors and its approach to the

development of new technology hampered those who intended to

use cover and denial and deception techniques to counter U.S.

space reconnaissance. As a result, knowledge of the NRO was

limited.

Experienced

Program Managers. NRO program managers have been experienced

military and CIA acquisition officers. Many have spent almost

their entire careers within the NRO working in many different

capacities. Because they were highly qualified acquisition professionals

and understood NRO activities so well, they required little

supervision and were empowered to make decisions not normally

made at their level in other parts of the U.S. Government. They

could reallocate funds to meet unforeseen circumstances and

could take advantage of opportunities to adopt new technologies.

With clear guidance from senior Government officials and sufficient

resources, they were able to make decisions in technically risky

programs and produce very successful, advanced space reconnaissance

systems.

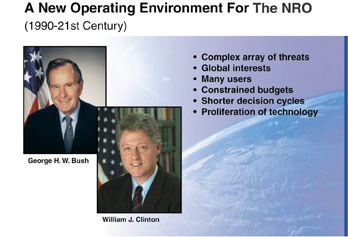

The

Impact of Change. The current environment within which the

NRO must operate has had an unfortunate effect on these characteristics,

which have been so important for the NRO's past successes. For

example, the integration of NRO information into many day-to-day

decision-making processes has made many national security professionals

very familiar with NRO programs. Many have come to expect the

NRO to adapt to standard procedures in order to accommodate

the needs of a wide array of customers.

The NRO

now must respond to rigid requirements for new reconnaissance

systems, based on extensive negotiations among a wide variety

of strategic and tactical customers. Because resources are constrained

across the Intelligence Community, cost constraints have become

an increasingly important element in decisions on new NRO programs.

There have

been other important changes. The Secretary of Defense-DCI partnership

is being managed to a large extent by subordinates or staffs.

The NRO is now a publicly acknowledged organization. Some of

its latest space reconnaissance initiatives are well-publicized

and NRO systems are analyzed and discussed on the Internet.

Thus, the

NRO is operating under very different conditions from those

under which it achieved its greatest successes. Nonetheless,

new, extremely difficult intelligence problems will continue

to arise that will require frequent, assured, global access

to denied areas. This is the NRO's unique contribution to intelligence

and should be the driving force behind its efforts.

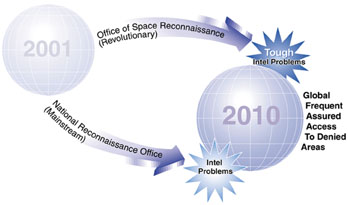

The

Office Of Space Reconnaissance

Because

of the NRO's changed circumstances, the Commission concludes

that the NRO Director must free his most advanced research,

development and acquisition efforts from processes that inhibit

his ability to place the latest and best reconnaissance capabilities

on orbit quickly. The Commission believes the best way to do

this is to create a new office that builds on the sources of

the NRO's past successes and reflects the characteristics of

its successful programs. It suggests the new office be called

the Office of Space Reconnaissance (OSR).

The first

and foremost premise in establishing this Office must be that

it responds only to requirements from the President, Secretary

of Defense and DCI through an Executive Committee (EXCOM) and

to congressional oversight. By implication, the Office's budget

would be relatively small and it would focus only on the most

significant problems confronting the three principal decision-makers

and that require space-based reconnaissance solutions. Because

these officials would give the new Office their personal attention,

they would exempt the Office from normal DoD acquisition regulations

and allow it to use, when appropriate, the DCI's special authorities

under 50 U.S.C. 403j. Further, their personal involvement and

support would give important impetus to the Office's programs

as they wind their way through the complicated budget and oversight

process.

Second,

the Office would focus narrowly on high technology solutions

to the most difficult intelligence problems based on the requirement

to gain frequent, assured, global access to denied areas. This

could produce space collection systems at least two generations

ahead of the rest of the world. The President, Secretary of

Defense and DCI would personally identify the problems and approve

the new Office's proposed solutions.

The third

premise for the new Office is that it should be under the control

and direction of the NRO Director. A single overall vision for

space reconnaissance must be retained, and that vision is best

vested in the NRO Director.

Fourth,

the Office must be staffed by both military and CIA personnel.

They bring the separate perspectives of strategic and tactical

customers to the program level of decision-making. The Commission

anticipates they would be senior grade officers with broad backgrounds

in space reconnaissance and with extensive experience in program

management and acquisition. Their experience and background

should be sufficient to give their supervisors and those with

oversight responsibilities, including the Congress, confidence

in the Office's program management. As a result, Office managers

would have the power to make risky technical decisions that

are often needed.

Fifth,

the Office would approach space reconnaissance programs from

end-to-end and cradle-to-grave perspectives. Its solutions would

be comprehensive, beginning with effective and efficient tasking

of a space reconnaissance system and ending with at least a

plan for the dissemination of its products.

Sixth,

the Office would operate from facilities separate from other

space reconnaissance activities, and it would be covered by

a new security compartment. The purpose would be to establish

effective secrecy to shield the technologies and collection

techniques under development. Accordingly, the Office would

have a greater likelihood of defeating adversary attempts to

employ cover and denial and deception techniques.

The Office

also would have a separate budget element included in the National

Foreign Intelligence Program. The Commission envisions that

funds for the new budget of the Office of Space Reconnaissance

would come initially from the National Reconnaissance Program.

The Commission has taken this approach so as to avoid simply

recommending that more funds be committed to space reconnaissance.

It believes the creation of the new Office will focus senior

level attention on high-end space reconnaissance solutions to

the most difficult intelligence problems. Further, the Commission

believes that, by having the new Office create and defend its

own budget, its advanced research, development and acquisition

programs would succeed or fail based on their own merits.

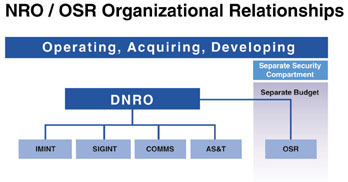

The Office

of Space Reconnaissance would be separate from the NRO in many

aspects. It would have a separate budget, separate facilities,

a separate security compartment, and separate program managers.

However, the NRO Director's (DNRO) relevant corporate structure

should be sufficient to support its activities.

The Commission

believes a new Office operating under the specific guidance

of the President, Secretary of Defense and DCI would be better

postured to place the most advanced reconnaissance capabilities

into space than would the current NRO operating mechanisms.

Those who oversee and supervise space reconnaissance activities,

including those in Congress, should have greater confidence

in the importance of programs personally supported by the President,

Secretary of Defense and DCI.

Additionally,

a smaller budget supporting fewer programs should enable supervisors

and those with oversight responsibilities to have a more thorough

understanding of each program and the significance of the technology

involved. This in turn should give them greater assurance that

technical decisions made at the program level are correct and

further reduce tendencies to hold back technology development

solely for cost reasons.

Finally,

the Office's new security compartment would permit access only

to those with oversight responsibilities who have an absolute

need-to-know. A proper balance must be struck, however, in which

secrecy is sufficient to frustrate adversaries using cover and

denial and deception techniques, while at the same time care

is given to protect only essential information.

The Commission

emphasizes that creation of the Office of Space Reconnaissance

does not diminish the fundamental importance of the NRO and

its mission. As noted throughout this Report, the Commission

finds the NRO is responding appropriately to the changed circumstances

confronting it. The Commission believes the NRO must continue

along the path it is following in order to serve a broad strategic

and tactical customer base.

The NRO

must continue to evaluate and put into place leading edge technologies

to improve space reconnaissance and to meet the needs of its

broad customer base. It also must develop and operate space

reconnaissance systems to overcome the intelligence problems

confronting this same customer base. It must acquire and operate

high-technology spacecraft on behalf of the Secretary of Defense

and DCI to gain frequent, assured access to denied areas on

a global basis.

Recommendation

-

The

Secretary of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence

should establish a new Office of Space Reconnaissance under

the direction of the Director of the NRO. The Office should

have special acquisition authorities, be staffed by experienced

military and CIA personnel, have a budget separate from other

agencies and activities within the National Foreign Intelligence

Program, be protected by a special security compartment, and

operate under the personal direction of the President, Secretary

of Defense and Director of Central Intelligence.

The

Secretary of

Defense-Director of Central Intelligence Relationship

The

tri-cornered arrangement among the Secretary of Defense, DCI

and NRO Director has at times provided great strength to the

NRO because it has allowed the NRO Director to draw on the resources

and benefit from the advocacy of the two major forces in the

Intelligence Community and DoD.

The Commission

has emphasized the need for the Secretary of Defense and DCI

to be fully aware of, and engaged in, NRO program decisions.

In that light, the Commission has reviewed the Secretary of

Defense and DCI responsibilities regarding the NRO.

The NRO

Director is the head of an agency of DoD that is also a major

component of the Intelligence Community. In addition, he serves

as the Assistant Secretary of the Air Force for Space. Under

four agreements dating back to the 1960s, the Director of the

NRO is responsible for reporting to both the Secretary of Defense

and the DCI. According to the NRO's General Counsel, all four

agreements are considered by the NRO to be still in effect,

although more recent statutory and Executive Order provisions

have added significant structure to the relationship. (See box

on facing page, "Summary of Secretary of Defense--DCI Agreements

Pertaining to the NRO." Also, a more detailed explanation

of the agreements and the historical development of the Secretary

of Defense-DCI relationship regarding the NRO is included in

Appendix D.)

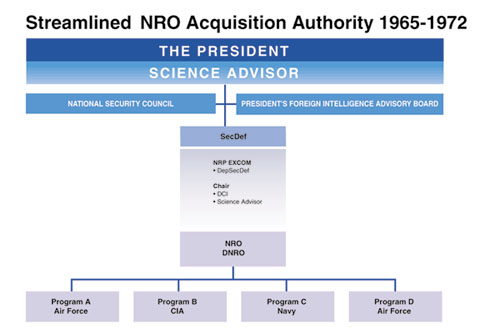

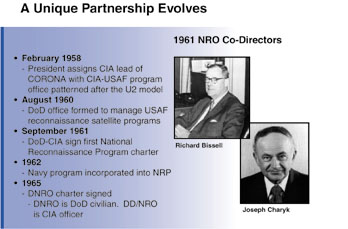

Summary

of Secretary of Defense--DCI Agreements Pertaining to

the NRO

The

first agreement (1961) created the NRO to manage a DoD

National Reconnaissance Program (NRP) that included all

overt and covert satellite and over-flight reconnaissance

projects. The NRO was to function under the joint direction

of the Under Secretary of the Air Force and the CIA's

Deputy Director for Plans. Major NRP program elements

and operations were to be subject to regular review by

a National Security Council group.

A second agreement (1962) provided that the NRO Director

would be designated by both the DCI and Secretary of Defense

and be responsible directly to them for management of

the NRP. DoD and CIA personnel were to be assigned to

the NRO and DoD and CIA were to provide funds for the

NRO projects for which they were responsible.

In 1963, a third agreement superseded the prior version

and identified the Secretary of Defense as the Executive

Agent for the NRP and the NRO as a separate operating

agency within DoD. The NRO Director was now to be appointed

by the Secretary, with the concurrence of the DCI. A Deputy

NRO Director was to be appointed by the DCI, with the

concurrence of the Secretary. NRO budget requests were

to be presented by the NRO Director to the Secretary and

DCI, the Bureau of the Budget and congressional committees.

The NRO Director was to report directly to the Secretary

of Defense, while keeping the DCI currently informed.

The last agreement (1965) made clear the Secretary of

Defense had "ultimate responsibility" for the

NRO and eliminated the requirement for DCI concurrence

in the selection of the NRO Director. The DCI retained

authority for appointing the Deputy NRO Director, but

with the concurrence of the Secretary. This agreement

also provided that the Secretary was the final decision-maker

for the NRP budget and all NRP issues. It created an NRP

Executive Committee (EXCOM)--consisting of the Deputy

Secretary of Defense, DCI and the Assistant to the President

for Science and Technology--to "guide and participate"

in NRP budget and operational decisions, but the Secretary

of Defense was responsible for deciding any EXCOM disagreements.

|

The tri-cornered

arrangement among the Secretary of Defense, DCI and NRO Director

has at times provided great strength to the NRO because it has

allowed the NRO Director to draw on the resources and benefit

from the advocacy of the two major forces in the Intelligence

Community and DoD. To some degree, however, the uncertain situation

in which the NRO finds itself today--requirements rising, budgets

level or falling, and customers and mission partners demanding

greater roles in the NRO's decision-making process--can be traced

to the ambiguity and recent inadequacy of the Secretary of Defense-DCI

relationship as a means of resolving disputes relating to the

NRO.

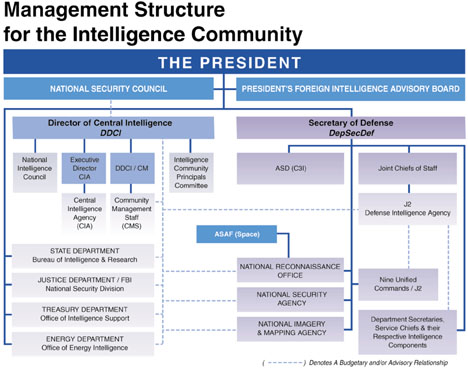

The Commission

believes history has shown it is possible for the NRO Director

to be responsive to both the Secretary of Defense and DCI and

that the dual reporting arrangement is valuable for the NRO

Director and should be continued. In previous years, for example,

the Secretary of Defense and DCI held weekly meetings that allowed

intelligence-related issues to be raised and resolved quickly

without having to percolate through the many layers of bureaucracy

that have come to separate the two officials from the NRO Director.

(See graphic, "Management Structure for the Intelligence

Community.") However, the Commission recognizes the relationship

is not self-executing and that its success requires the active

participation of both parties.

The Secretary

or the DCI may choose not to pursue this relationship. Successively

lower levels of officials may then be left to "manage"

the NRO on behalf of the two principals. Friction among the

NRO, the Intelligence Community and DoD has developed in such

periods. The Commission believes that the Secretary of Defense

and DCI must be involved in managing the NRO and that a close

working relationship must be established between them for this

purpose.

The Secretary

of Defense-DCI relationship with regard to the NRO could be

embodied in a comprehensive statute, as there is for NIMA, or

it could be established by statute mandating its completion

by a date certain. Alternatively, relatively minor amendments

could be made to the existing statutory scheme that would have

significant impact on the relationship. The relationship also

could be established by Executive Order or some other form of

Presidential Directive, a combination of statutory and Executive

Branch provisions, or a new agreement between the Secretary

of Defense and the DCI that would take account of the many changes

in the relationship that have occurred since 1965, the date

of the last of the previous agreements.

The Commission

evaluated the desirability of recommending the creation of an

"NRO statute." Such a law could firmly secure the

NRO's position in the national security community. After debate,

the Commission concluded that congressional action in this regard

could make the situation worse, rather than better. It believes

senior level Executive Branch attention should be sufficient

at this time.

Recommendations

-

The

President must take direct responsibility to ensure that the

Secretary of Defense and Director of Central Intelligence

relationship regarding the management of the NRO is functioning

effectively.

-

The President should direct the development of a contemporary

statement defining the relationship between the Secretary

of Defense and Director of Central Intelligence with regard

to their management of the NRO.

Balanced

Response to Customer Demands

Ensuring

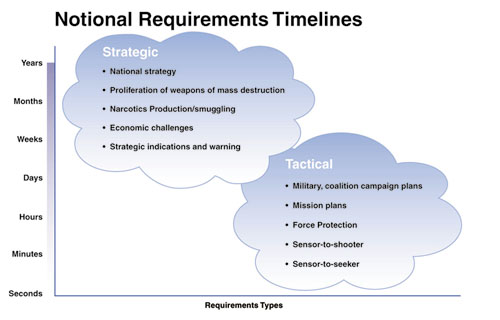

a proper balance between strategic and tactical requirements--in

terms both of the use of current NRO systems and in the design

of future NRO systems--is a matter of utmost national security

importance.

Strategic

and tactical intelligence requirements determine the targets

against which current NRO systems collect every day. They also

have a direct and substantial impact on the design parameters

of future NRO systems.

Tactical

requirements include those generated by the Defense Intelligence

Agency, the military departments of DoD and the commanders of

the various U.S. military commands. They are generated in furtherance

of the U.S. military's responsibility to cope with contingencies

in any area of the world, to support the worldwide deployment

of U.S. armed forces and to organize, train and equip forces

for future military operations.

Strategic

requirements, on the other hand, include those generated by

the National Security Council, CIA, DoD, State Department, and

other civilian departments and agencies. These requirements

support U.S. Government policy officials, including those in

the White House and throughout the various departments and agencies

of the U.S. Government who participate in the development of

U.S. foreign, defense, military, economic, and technology policies.

An extensive

debate has been underway for some time over whether NRO collection

resources are being properly allocated between strategic and

tactical intelligence requirements. The Jeremiah Panel, referred

to earlier, reviewed the state of the NRO and reported in 1996

that both strategic and tactical customers of the NRO were frustrated

with the requirements processes for both future systems and

daily operations. According to the Panel report, tactical customers

believed there was an insufficient NRO commitment to satisfying

their needs, while strategic customers believed that overhead

systems were being used, and future systems designed, primarily

for tactical customers and to the detriment of strategic customers.

The NRO

Director identified this tension between the NRO's strategic

and tactical customers as the first issue the Commission should

address because there is a belief that the NRO is responsible

when requirements are not satisfied. Substantial as the NRO's

present collection resources are, they cannot satisfy all requirements

all the time. Nor will future NRO systems, including the Future

Imagery Architecture, be able to satisfy all the needs of both

strategic and tactical customers. The NRO is thus caught in

the middle of the debate over the respective extents to which

strategic and tactical requirements should be satisfied by its

current systems and over the influence of those requirements

on the design of its future systems.

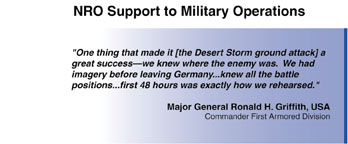

The classification

level of much of the data produced by NRO systems was lowered

during and after the Gulf War in response to congressional and

military pressure to make it more readily available to military

commanders in the field. As explained earlier, this action removed

the veil of compartmented secrecy from the NRO. In addition,

following the Gulf War, Congress emphasized the need to expand

the use of NRO systems to support military operations.

These developments

have brought a substantial increase in NRO collection requirements.

But there has been no corresponding increase in NRO funding.

As has been explained elsewhere in this Report, the program

for providing additional funds to the NRO from the DoD budget

through the Defense Space Reconnaissance Program for activities

related to military-unique requirements was eliminated in 1994.

Without such compensating resources, the shift toward expanded

support for military operations has stressed the capacities

of NRO systems to satisfy strategic, longer-term intelligence

needs.

The Commission

believes that ensuring a proper balance between strategic and

tactical requirements--in terms both of the use of current NRO

systems and of the design of future NRO systems--is a matter

of utmost national security importance. Factors that have made

this an issue include the growing expectations of the NRO's

expanding customer base and the lack of an effective policy

structure to clarify the NRO's mission and the allocation of

its resources in the face of these competing demands.

There also

appears to be no effective mechanism to alert policy-makers

to the negative impact on strategic requirements that may result

from strict adherence to the current Presidential Decision Directive

(PDD-35) assigning top priority to military force protection.

That Directive has not been reviewed recently to determine whether

it has been properly applied and should remain in effect.

It also

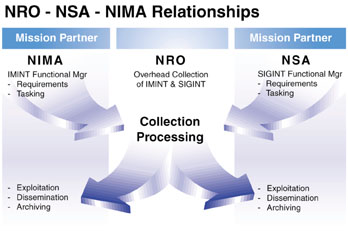

is significant that the interagency committees and components

that consider requirements for NRO systems were moved out of

the DCI's Intelligence Community management structure in the

early 1990s. These are now managed by the agencies with functional

responsibilities for the management of signals intelligence

(SIGINT) and imagery intelligence (IMINT), NSA and NIMA, rather

than being directed by officials with a broader view of the

needs of the Intelligence Community.

Day-to-day

collection requirements for current NRO IMINT systems are managed

by NIMA through an interagency process that includes representatives

of both the national and military customers. This process allocates

tasking of NRO imagery systems according to standing requirements

based on predetermined intelligence priorities. It allocates

daily tasking of these NRO systems in response to ad hoc requirements,

driven by current events, that may warrant a higher collection

priority. A similar, but somewhat more complicated, process

regarding collection requirements for NRO SIGINT systems is

managed by NSA.

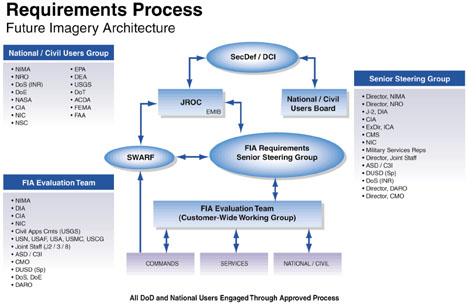

Requirements

that will affect the design of future NRO IMINT and SIGINT systems

must be developed, presented and justified prior to the design

of those systems. This is a more technical and detailed process

than that for current requirements, and it may take months or

years. It also requires a sophisticated assessment by the NRO

and others of the cost and feasibility of providing the technology

needed to satisfy the various requirements set forth by the

customers. The most recent example was the 18-month requirements

process for the NRO's Future Imagery Architecture (FIA).

In the

FIA requirements process, the DoD customers benefited from a

well-established and systematic DoD requirements review process.

To aid non-DoD customers in developing and justifying such requirements

in the future, a Mission Requirements Board has been created

under the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence for Community

Management. If this Board functions properly, it should allow

strategic customers to compete on a more even footing with the

tactical customers.

It is clear

to the Commission that, in this area as well, it is up to the

President, Secretary of Defense and DCI to ensure that the priority

needs of both the strategic and tactical customers of intelligence

from NRO systems are satisfied now and in the future. The Commission

believes that direct and sustained attention by the Secretary

of Defense and the DCI is needed to resolve the current debate

in a way that ensures sufficient and proper coverage of both

strategic and tactical intelligence requirements by current

and future NRO reconnaissance systems.

In any

event, the President has assigned the highest current priority

to collection of intelligence in support of deployed U.S. military

forces. So long as this is the case, the needs of the strategic

customers will continue to be given secondary priority whenever

the two types of requirements conflict and the NRO systems cannot

accommodate both.

Recommendations

-

The

Secretary of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence

must work closely together to ensure that proper attention

is focused on achieving the appropriate balance between strategic

and tactical requirements for NRO systems, present and future.

-

The Presidential Decision Directive (PDD-35) that establishes

priorities for intelligence collection should be reviewed

to determine whether it has been properly applied and should

remain in effect or be revised.

-

The imagery intelligence and signals intelligence requirements

committees should be returned to the Director of Central Intelligence

in order to ensure that the appropriate balance and priority

of requirements is achieved each day.

-

The Secretary of Defense and Director of Central Intelligence

should undertake an educational effort to ensure that Intelligence

Community members and customers are properly trained in the

requirements process, the cost of NRO support, and in their

responsibilities in requesting NRO support.

Defense

Space Reconnaissance Program (DSRP)

Pressures

on the National Foreign Intelligence Program to address requirements

that are uniquely military in nature are increasing and there

is no longer a DoD budget program element to offset the rising

cost to the NRO of meeting those requirements.

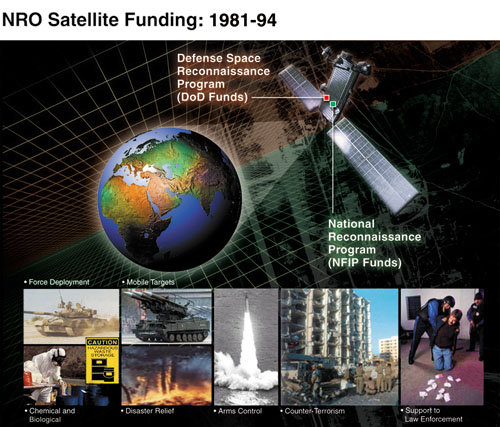

In the

1970s, the NRO's satellite collection capabilities and products

began to be made more broadly available to the military. The

expanded use of this data spawned the creation in 1981 of the

Defense Support Project Office (DSPO) within the NRO. DoD established

the Defense Reconnaissance Support Program (DRSP), under the

management of the DSPO, and used it as a mechanism to provide

additional funds from DoD to the NRO for systems development

and operations that directly contributed to the support of tactical

military users. Congress later authorized and appropriated specific

funding to the DSPO within the DRSP budget to ensure that military

warfighting requirements were addressed in the design and operation

of NRO satellites.

The DRSP

funds were generally used to meet unique military requirements

for NRO satellite reconnaissance systems. These funds, on the

order of several hundreds of millions of dollars, paid for additional

satellites or military-specific systems. The DRSP budget was

managed by the DSPO. The NRO Director also served as the Director

of the DSPO, thus ensuring that NRO program offices were responsive

to the needs and requirements of both the Intelligence Community

and the military departments.

Between

1981 and 1994, the NRO was authorized and appropriated annual

funds from both the National Reconnaissance Program (NRP) element

of the National Foreign Intelligence Program budget (NFIP) and

the DRSP element of the Tactical Intelligence and Related Activities

(TIARA) program budget. The NRP was used to pay for Intelligence

Community requirements for development, operation and maintenance

of NRO satellite reconnaissance systems, as well as NRO innovative

technology activities. Supplemental funding for NRO efforts

to satisfy military requirements was provided from DoD's DRSP

budget.

A 1994

agreement between the Deputy Secretary of Defense and the DCI

transferred all of the satellite acquisition and infrastructure

funding into the NRP. As a result, DRSP funding was reduced

to tens of millions of dollars per year to be spent on helping

military customers learn how to use collection and processing

systems effectively. The DRSP was renamed the Defense Space

Reconnaissance Program (DSRP).

The effect

of this 1994 agreement is that NRO efforts to support both Intelligence

Community and military requirements are now paid for out of

the NRP budget. In 1999, Congress directed the abolition of

the DSPO and its functions were transferred to the NRO Deputy

Director for Military Support.

As explained

earlier, military requirements have continued to grow and contention

for NRO satellite resources has increased. The number of extended

U.S. military commitments and other U.S. interests around the

globe that require continuing support is also stressing the

capacity of NRO reconnaissance systems to detect critical indications

and warnings of potentially threatening events.

Pressures

are increasing, as a result, on the NRP and NFIP to address

these requirements--even those uniquely military in nature.

Yet there is no longer a DoD budget program element to offset

the rising cost of meeting those requirements as there was when

the DRSP competed against other DoD budget requirements to provide

the needed funds.

Experience

since 1994 suggests that adaptations of NRO systems for tactical

purposes have met with increasing difficulty competing within

the NFIP budget and that NRP spending on tactical needs is seen

as a drain on the Intelligence Community and the NFIP. Military

influence toward improving the tactical support capabilities

of future satellite systems is limited because the Intelligence

Community believes that many of the proposed improvements are

DoD-unique and should not be paid for by the NFIP.

The Commission

believes it is time to reinstitute DSRP funding for NRO programs.

Besides easing the budget pressures, this would help sensitize

military users to the costs associated with added requirements

and reduce the current tendency to view NRO products as a "free"

commodity with no value attached and no cost-benefit measurement

against competing demands.

The Commission

supports the language in the report accompanying the Fiscal

Year 2001 DoD Authorization Act that parallels the findings

of the Commission. That report states that the DSRP has served

an important role in providing direct interactions among the

NRO and operational military commanders and other elements of

DoD. It also states that the Secretary of Defense needs to evaluate

the overall role of the NRO in supporting tactical military

forces.

This evaluation

is to include a review of, among other things, whether a revitalized

DSRP would be the best mechanism for giving the Unified Commands

a role in determining future space intelligence and reconnaissance

capability requirements and raising the visibility of space

reconnaissance matters within the DoD program planning and resource

allocation process. The evaluation also is to include the role

of a revitalized DSRP in funding NRO system developments to

satisfy unique military requirements. The Authorization Report

directs the Secretary of Defense to provide the congressional

defense and intelligence committees a report by May 1, 2001

on his assessment and recommendations in these regards.

Recommendation

-

The

Secretary of Defense, in consultation with the Director of

Central Intelligence, should re-establish the Defense Space

Reconnaissance Program as a means of funding tactical military

requirements for NRO systems and architectures.

Increased

Resource and Budgetary Flexibility

The

DCI should have greater latitude to redirect funds among intelligence

collection areas and agencies in order to respond most effectively

to the specific types of program issues that arise at the NRO.

The provisions

of the 1997 Intelligence Authorization Act were intended, among

other things, to enhance the authority of the DCI in regard

to the annual NFIP budget. Thus, the DCI is required to approve

any reprogramming of NFIP funds by any Intelligence Community

element.

The DCI

was also given authority to transfer funds or personnel within

the NFIP budget to meet unforeseen and higher priority intelligence

requirements. However, that authority is conditional on the

agreement of the "Secretary or head of the department which

contains the affected element or elements...." This requirement

for agreement could negate the DCI's ability to move personnel

and financial resources around the Intelligence Community, including

to or from the NRO, to deal with unexpected contingencies and

technological or other developments.

In this

respect, the Commission notes that Section 105 of the FY 2001

Intelligence Authorization Act has ameliorated this situation

somewhat in favor of the DCI. That section provides that only

the Secretary or head of an agency has the authority to object

to a transfer of funds within the NFIP and that such objections

must be in writing. The Act further provides that, within the

Department of Defense only, the Deputy Secretary of Defense

may be delegated the authority to object for the Secretary and

that the Deputy Director of Central Intelligence for Community

Management may be delegated the DCI's authority to transfer

funds.

Recommendations

-

The

Director of Central Intelligence should be granted greater

latitude to redirect funds among intelligence collection activities

and agencies in order to respond most effectively to the specific

types of issues that arise in NRO programs.

-

Transfers greater than $10 million would continue to require

the concurrence of the affected Secretary or agency head.

This could be coupled with a provision to allow a Secretary

or agency head who has objections to such transfers the opportunity

to appeal the Director of Central Intelligence's decision

to the President.

-

The requirement that such transfers be made known to the appropriate

congressional committees should not be altered.

NRO

Technical Expertise

The

Commission believes there is a compelling need for an NRO career

path and assignment policy that provides the opportunity for

highly trained engineers and acquisition and operations specialists

to be assigned to and progress through a broad range of NRO

positions.

The NRO's

success is directly attributable to the high quality and creativity

of the DoD, CIA and contractor workforce that has been dedicated

to supporting the NRO. The overwhelming majority of the U.S.

Government personnel who work at the NRO are employees of the

CIA or DoD who have been assigned to the NRO for some portion

of their careers and who have the technical expertise needed

for complex NRO programs. A substantial number of these are

active duty military personnel.

Until recently,

many of these personnel served the majority of their careers

with the NRO, transferring among its acquisition, development,

launch, and operating elements. Some never returned to their

parent organization for any appreciable length of time. This

allowed a highly skilled cadre of personnel to advance within

the management structure of the NRO, gaining experience at various

levels of its technical, financial and acquisition programs

along the way. Promising young military and CIA officers were

groomed to become the NRO program managers of the future. Long

tenure and accomplishment at the NRO were valued by their parent

organizations and these personnel were promoted along with,

and sometimes ahead of, their peers who followed more traditional

career paths within their agency or military service.

With the

transition from separate programs to a functionally-based organization,

there is no longer a unique career path for many of the personnel

assigned to the NRO. For example, in the past when there were

independent Air Force, CIA and Navy elements called Programs

A, B, C, and D, Air Force personnel in Program A were assigned

to the Secretary of the Air Force Office of Special Programs

(SAFSP). They were hand-selected for assignment to the NRO and

their careers were managed by SAFSP. This Air Force element

was directly tied to the strategic mission of the Air Force

to monitor the Soviet Union's nuclear forces. As a result, there

were clear incentives for the Air Force to contribute to the

NRO mission, promote Air Force identity and mentor and care

for its people efficiently.

Likewise,

Program B, which was staffed by personnel from the CIA's Directorate

of Science and Technology (DS&T), had its own unique identity

and career path within the DS&T Office of Development &

Engineering. Those personnel also were hand-selected for a career

within the NRO. They were tied directly to the CIA's strategic

intelligence mission and the requirements generated by the DS&T

and had very clear objectives and career paths to become managers

of the NRO's Program B systems.

New personnel

assignment practices adopted by the parent organizations have

had the effect of limiting the tenure of personnel assignments

to the NRO. Because rotational assignments back to these organizations

appear to be a requirement for career advancement beyond a certain

grade, there is a resulting concern that the NRO could lose

its ability to sustain the cadre of highly-skilled and experienced

personnel it needs to guarantee mission success. In some cases,

this cadre is prevented from gaining equivalent broad space-related

experience during the rotational assignments. While it is understandable

that a parent organization may want to exploit the special skills

their personnel develop in the NRO, the cost to NRO space reconnaissance

programs is likely to be greater than the value of broader experience

to these other organizations.

In fact,

serving too much time supporting the development and acquisition

of our nation's most sensitive and unique space reconnaissance

systems is often seen as detrimental to one's career. Also,

there are no longer any separate military service elements (Air

Force, Navy, and Army) within the NRO to monitor personnel assignments

or career progression.

The Commission

believes there is a compelling need for an NRO career path and

assignment policy that allows highly trained engineers and acquisition

and operations specialists to be assigned to and progress through

a broad range of NRO positions. In this respect, the Commission

notes that Section 404 of the FY 2001 Intelligence Authorization

Act enables the DCI to detail CIA personnel to the NRO indefinitely

on a reimbursable basis and to hire personnel for purposes of

detailing them to the NRO.

The Commission

recognizes that there may be assignment possibilities within

other U.S. Government space or technical programs that could

contribute to the professional development of these personnel.

However, the technical complexity of NRO systems is unique,

and mission success requires the continuity of a dedicated cadre

of personnel skilled in the development, acquisition and operation

of those systems.

Recommendation

-

The

Secretary of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence

should jointly establish NRO career paths to ensure that a

highly skilled and experienced NRO workforce is continued

and sustained.

Increased

Launch Program Risks

There

appears to be no national strategy or effective and engaged

National Security Council-level mechanism to provide the guidance

and oversight needed to ensure a robust national space reconnaissance

architecture. This has led to a situation in which failures

in existing or new spacecraft and launch vehicles could result

in significant gaps in the intelligence coverage that is available

from NRO systems.

The Commission

believes the current status of the NRO satellite and launch

program dramatically highlights the need for active participation

and leadership by the Secretary of Defense and DCI in managing

the nation's space reconnaissance program. Because the NRO is

managed jointly by the Secretary of Defense and DCI, it is essential

that its operating responsibilities be clear and allow for sufficient

review of program decisions by other affected agencies. Such

reviews are consistent with the responsibilities of the Secretary

of Defense and DCI to assure global access through space reconnaissance.

Without such senior involvement, there is a real risk that NRO

program decisions will be made without a full appreciation of

their consequences for overall national security.

The Commission

is alarmed that one particular potential vulnerability in the

NRO's programs has arisen that might have been avoided with

proper foresight, leadership and review at the national decision-making

level. The NRO is now on a path that leads toward a future period

of unprecedented risks inherent in concurrent satellite and

launch vehicle development and transition. It is developing

new spacecraft that will be launched by new launch vehicles.

Today, the fragility of the satellite and launch architectures

offers no margins for error.

Historically,

spacecraft and launch vehicle development programs have failed

to meet their original estimated delivery dates. In addition,

the initial spacecraft and launch vehicles that emerge from

new development programs have often experienced failures because

of design flaws that were not discovered prior to their first

flights. In the past, such delays and failures could usually

be mitigated because the NRO either had robust satellite capabilities

in orbit, or had satellites or launch vehicles in production

that could be accelerated to fill any gaps.

Today,

however, sufficient NRO contingency capability does not exist

and has not been budgeted. The number of current launch vehicles

that remain available to the NRO until the U.S. Government-sponsored

Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) program is completed

is strictly limited to those necessary for planned NRO launches.

In addition, the NRO has adopted more optimistic assumptions

for the operational lifetimes for its current satellite systems

than it has in the past.

The NRO

believed that a significant number of commercial and other U.S.

Government launches would demonstrate the reliability of EELV

launch vehicles long before the NRO would be required to launch

its newly developed satellites on them. This has not happened

and current launch projections indicate NRO satellites are scheduled

to fly on very early EELV launch vehicles.

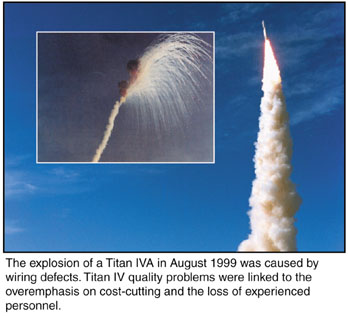

In addition,

the EELV and some NRO satellites under development are now using

an acquisition reform management approach that may cut costs,

but has proven to be controversial since it involves less participation

by skilled U.S. Government and contract personnel in overseeing

the work of satellite and launch vehicle manufacturers. NASA

has acknowledged that some of its recent satellite problems

directly correlate with programs involving less Government participation

and use of acquisition reform techniques. The application of

these new acquisition reform techniques and commercial practices

to the EELV, and to some NRO programs, may add additional risks

and uncertainty relative to technical, schedule and cost success.

The Commission

is vitally concerned about the implications of this unprecedented

period of concurrent satellite and launch vehicle development

and transition that could have major impacts on the U.S. space

reconnaissance program. The decisions that have brought about

this situation have been based upon resource constraints and

NRO assessments. The decisions have not been adequately reviewed

at the highest levels of the U.S. Government to assess their

overall implication for the national security posture.

The Commission

notes the painful lesson of the 1980s that grew out of the decision

to launch all NRO satellites from the Space Shuttle. Following

the Challenger disaster and the suspension of Space Shuttle

flights, the NRO was forced to reconfigure its satellites for

other launch vehicles. This cost billions of dollars and placed

U.S. national security at risk during the period when replacement

satellites could not have been launched if circumstances had

so required.

There appears

to be no national strategy or effective and engaged National

Security Council-level mechanism to provide the guidance and

oversight needed to ensure a robust national space reconnaissance

architecture. This has led to a situation in which failures

in existing or new spacecraft and launch vehicles could result

in significant gaps in the intelligence coverage that is available

from NRO systems.

Recommendations

-

The

NRO Director, with the support of the Air Force Materiel Command

and Space and Missile Systems Center, should develop a contingency

plan for each NRO program or set of programs. These plans

should describe risks, contingency options and failure mitigation

plans to minimize satellite system problems that might result

from satellite or launch vehicle failures.

-

The Secretary of Defense and Director of Central Intelligence

should establish independent teams to conduct pre-launch assessments

of non-traditional areas of risk. These teams should be made

up of recognized space launch experts and be granted whatever

special authorities and accesses are required to perform their

duties.

-

The Commission to Assess United States National Security Space

Management and Organization should evaluate the need for an

improved organization structure to provide launch capability

and operations for the deployment and replenishment of NRO

and DoD satellites.

Commercial

Satellite Imagery

The

U.S. Government could satisfy a substantial portion of its national

security-related imagery requirements by purchasing services

from the U.S. commercial imagery industry.

Background.

The NRO's future could be affected significantly by the degree

to which it is able to exploit the ongoing development of a

competitive commercial space imagery industry. That industry

is in an embryonic stage in the United States and abroad, but

the technology available to it is already mature. According

to a recent classified U.S. Government study, the U.S. Government

could satisfy a substantial portion of its national security-related

imagery requirements by purchasing services from the U.S. commercial

imagery industry.

The National

Space Policy promulgated by Presidential Decision Directive-49

in September 1996 includes Commercial Space Guidelines to promote

the development of a competitive U.S. commercial space imagery

industry. The stated goal of the Policy is to enhance U.S. commercial

space activities while at the same time protecting U.S. national

security and foreign policy interests.

The Policy

further directs U.S. Government agencies to purchase "commercially

available" space goods and services to the fullest extent

"feasible" and not to conduct activities with commercial

applications that deter commercial space activities, except

for reasons of national security or public safety.

|

| One-meter

pan-sharpened color image of the U.S. Capitol, collected

by Space Imaging's Iknoos satellite. This image demonstrates

current, first-generation commercial space imagery capability. |

The 1996

Space Policy also explains that the U.S. Government will not

provide direct federal subsidies to the commercial space industry.

It should, however, facilitate "stable and predictable"

U.S. commercial sector access to appropriate Government space-related

hardware, facilities and data to stimulate private sector investment

in and operation of space assets.

Over the

last several years, NRO and NIMA officials have considered the

means by which the commercial imagery industry could complement

U.S. Government collection, analysis and dissemination capabilities

to support Government needs. Substantial Government purchases

of commercial imagery were promised. As a result, there were

high expectations in the private sector.

However,

such purchases have been relatively insignificant. Questions

have been raised about the effectiveness of the Government's

plan for buying imagery products and services. Criticism has

been directed at the process for transferring Government technologies

that will be needed if the U.S. commercial imagery industry

is to be successful. How these issues are resolved will have

a great impact on the long-term viability of the industry and

its ability to generate products and services of use to the

U.S. Government.

Space

Imagery as a "Commodity." The basic technology

for collecting and processing high-resolution images from

space has become available to an increasing number of nations.

Ally or adversary, all nations that have developed or are

developing a space-based imagery capability have expressed

an intention to serve civil sector needs and, in most cases,

to offer the images to the commercial market.

Government

Acquisition of Commercial Imagery. Over time, the Government

has clearly tended toward greater dependence on private sector

sources for many of its needs. This has included an extraordinary

range of technologies, components, subsystems, and services,

as well as integrated systems ranging from microelectronics

to space launch vehicles.

A decision

to rely on commercial imagery to supply some portion of U.S.

Government imagery needs necessarily raises questions about

whether the private sector can be relied on to provide services

of sufficient quality and timeliness. Further questions relate

to how best to structure Government procurement of commercial

imagery.

Of no less

importance is the question of whether domestic or international

sale of high-resolution images will adversely affect the interests

of the U.S. Government. These interests include ensuring the

security of U.S. and allied military deployments and operations

and preventing U.S. adversaries from acquiring information that

will aid them in conducting denial and deception operations.

The U.S.

commercial imagery industry has made substantial investments

in current first-generation space imaging systems and it proposes

to make even larger investments in planned second-generation

systems. It is also making additional investments to improve

the quality, accuracy and timeliness of these systems. Many

of these improvements respond to earlier U.S. Government assessments

that were skeptical of the utility of commercial imaging systems

to the Government.

The commercial

imaging industry has received mixed signals from the U.S. Government.

While the NRO and NIMA have publicly expressed support for the

commercial imaging industry, only minimal Commercial Imagery

Program funding has been made available to the industry and

future funding has not been added.

The lack

of U.S. Government commitment to acquire commercial imagery

is further demonstrated by managerial problems that have emerged

in NIMA's Commercial Imagery Program. There is no continuity

in the Program and the program manager has been changed frequently.

The Commission

supports Government purchases of one meter and one-half meter

resolution commercial imagery, which can meet a large percentage

of U.S. Government imagery requirements. Because of the lack

of demonstrated commitment, the Commission believes there is

a need for an overall assessment--independent of the NRO--of

the utility of commercial technologies to supplement traditional

NRO missions.

Assuming

that imagery of the required resolution and timeliness is available

from both the NRO and the commercial imagery industry, under

present procedures NIMA will have a natural preference for NRO

imagery over commercial imagery. NIMA does not have to purchase

NRO imagery; it is "free."

To deal

with similar tendencies in determining whether to use military

or commercial airlift capabilities, DoD has created an industrially

funded account. The manager of this account determines for the

customer whether military or civilian airlift best meets the

customer's needs within the budget resources available. Thus,

the use of a C-17 aircraft for a routine peacetime cargo flight

to a modern European airport is unlikely since a commercial

aircraft could perform the same task far more cheaply. The military

aircraft would be chosen when circumstances (e.g., unprepared

runways) justify doing so.

With regard

to U.S. Government imagery requirements, a number of critical

national security interests can only be met by Government systems.

However, a large number of targets can be covered by commercial

capabilities. Through an approach to imagery analogous to DoD's

military/civilian airlift practice, Government systems would

be focused on targets where their unique capabilities in resolution

and revisit times are important, while commercial systems would

be used to provide processed "commodity" images.

In the long

term, such a division of labor between the public and private

sectors will allow the commercial sector to develop without

a U.S. Government subsidy. A predictable market will be created,

and private sector investors will be able to establish an infrastructure

to meet predictable U.S. Government needs. Current Government

acquisition practices for commercial imagery have helped create

an unpredictable market. This substantially increases the risk

to investors and diminishes the ability of the commercial imagery

sector to meet U.S. Government needs.

Government Licensing of Commercial Imagery Systems. In March

1994, President Clinton signed Presidential Decision Directive

(PDD)-23 establishing a policy permitting U.S. firms to obtain

licenses to market imagery products and systems commercially.

Its stated goal was to enhance U.S. competitiveness in space

imagery capabilities, while protecting U.S. national security

and foreign policy interests.

Delays

in the U.S. Government licensing approval process, along with

several recent failures in commercial satellite ventures and

the mixed signals on purchases by the U.S. Government described

earlier, are causing investors to reevaluate their financial

support for the U.S. space imagery industry. This financial

environment, coupled with the decline in the scale and pace

of U.S. Government satellite programs, is weakening the portion

of the U.S. industrial base that provides the foundation for

the NRO's space programs. The skilled workforce on which both

the NRO and the commercial imagery industry rely has been eroding,

while research and development investment that leads to the

technological change necessary for the United States to maintain

its global dominance in space has been falling.

In some

cases, particularly those involving "first time" applications

for licensing of newer technologies, U.S. commercial imagery

firms report having faced delays of more than 30 months in getting

responses to licensing applications. This is far longer than

even the processing time now needed for an export license for

defense products.

Planning,

building and placing a commercial satellite in orbit requires

approximately three to five years to meet required launch and

replenishment schedules. In the private sector, strict adherence

to these schedules is essential to persuade customers and investors

that services will be provided as advertised and that earnings

projections will be met. Obviously, a wait of three years for

the needed license approvals is not consistent with a commercial

space imagery initiative on a five-year development schedule.

The way

in which U.S. policy on licensing of commercial imagery initiatives

is being implemented is likely to have an adverse effect on

the long-term security, commercial and industrial interests

of the United States. The present impediments to acquisition

and development of commercial imagery will diminish the industrial

base available to support U.S. Government space-based imagery

needs.

Meanwhile,

foreign competitors in the commercial imagery industry enjoy

relative freedom from U.S. export and licensing controls. These

foreign firms could dominate the global remote sensing market

in the 2005 timeframe if their U.S. counterparts are stymied

by an ineffective national strategy and a U.S. Government bureaucracy

that cannot keep pace with the global marketplace. The United

States is in danger of losing an opportunity to develop this

market, while stimulating foreign investment in it.

U.S. Defense

and Intelligence Community officials are justly concerned that

such high-resolution imagery could give adversaries of the United

States the ability to monitor U.S. intentions and capabilities,

particularly during future crises involving tactical military

operations. While this risk certainly exists, current law allows

the United States to exercise "shutter control" over

U.S. commercial space imagery vendors and systems where necessary

for national security or foreign policy reasons. This authority

alleviates the risk to some extent.

More significantly,

however, impeding the access of U.S. industry to this market

is more likely to increase, rather than diminish, this risk

by creating incentives for investors to create a capability

outside the United States. Several countries are likely to possess

high-resolution imagery satellites by 2005. As a result, whether

or not U.S. companies are granted licenses to proceed with such

systems, it appears that high-resolution imagery eventually

will be available on the open market to anyone who can afford

the price.

Report

of the National Imagery and Mapping Agency Commission. As

the Commission was in the final stages of preparing this Report,

the Commission to Review the National Imagery and Mapping Agency

(NIMA) made its report available. The Commission is pleased

to note that the findings and recommendations of both reports

are in close agreement in the area of commercial imagery. The

Commission also joins the NIMA Commission in applauding the

National Security Council's recent decision to approve two license

applications for a one-half meter resolution commercial imagery

satellite.

Recommendations

-

A clear national strategy that takes full advantage of the

capabilities of the U.S. commercial satellite imagery industry

must be developed by the President, Secretary of Defense and

Director of Central Intelligence.

-

The strategy must contain a realistic execution plan--with

timelines, a commitment of the necessary resources and sound

estimates of future funding levels.

-

The strategy also should remove the current fiscal disincentives

that discourage use of commercial imagery when it is technically

sufficient to meet user needs.

-

The NRO should work with NIMA to develop a new acquisition

model for commercial imagery that will help create the predictable

market necessary for the industry to become a reliable supplier

to the U.S. Government. The acquisition model should include

provisions for the pricing of imagery to the user from either

the commercial or Government sources that reflect the cost

of acquiring such images to the U.S. Government.

-

The Secretary of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence

should develop a strategy that recognizes the threat posed

to the United States by the likely availability of commercial

space imagery to opponents of the United States.

NRO

Airborne Reconnaissance Responsibilities

Too

often, space reconnaissance and strategic airborne reconnaissance

are viewed as mutually exclusive capabilities.

Strategic

airborne reconnaissance requires serious attention. The earliest

NRO reconnaissance successes included strategic airborne, as

well as space, platforms. Examples include the U-2 and SR-71

aircraft. Although the NRO still has responsibility for such

systems according to a 1964 DoD Directive still in effect, the

Commission is unaware that any strategic airborne reconnaissance

systems are being considered for further development by the

NRO.

Too often,

space reconnaissance and strategic airborne reconnaissance are

viewed as mutually exclusive capabilities. In fact, they are

quite complementary and contribute unique support to a tiered

concept of intelligence collection.

Space-based

reconnaissance can monitor the entire globe in an unobtrusive,

non-threatening way. However, satellites cannot supply long-term,

uninterrupted, focused, multi-intelligence coverage of a limited

area of interest. Airborne reconnaissance can supply excellent

coverage of limited areas, but can be threatened by hostile

action and affected by over-flight restrictions.

Aircraft

payloads can be changed for specific missions and updated as

technology improves. Satellite payloads are fixed in design

early and flown for the life of the vehicle with limited ability

to update functions. If a tiered collection management scheme

were used to combine satellite "tip off" and "deep

look" capabilities with aircraft flexibility and dwell

capabilities, national strategic and tactical requirements would

be well served.

In the

early 1990's, the Defense Airborne Reconnaissance Office (DARO)

was established. This was intended in part to provide a comprehensive

approach to all strategic and tactical airborne reconnaissance

platforms. When DARO was abolished, responsibilities for the

development of airborne reconnaissance systems passed to the

military services. The Intelligence Community therefore has

to depend on the military services for intelligence from airborne

platforms.

Very high

altitude, long range airborne reconnaissance systems provide

strategic value and accessibility. These systems merit continued

examination by the NRO in light of the features they share in

common with space systems.

To achieve

and maintain a proper balance between space-based and airborne

reconnaissance, the Commission believes the NRO needs to restore

its interest in airborne platforms and participate in engineering

studies to select the proper platform for the required mission.

Recommendation

-

The NRO should participate jointly with other agencies and

departments in strategic airborne reconnaissance development.

Specifically, the NRO should supply system engineering capabilities

and transfer space system technologies to airborne applications.

|