Executive

Summary

Changes

in The National Security Environment

The Commission

found that NRO reconnaissance satellites have had a crucially important

role during the past four decades in providing American Presidents

a decisive advantage in preserving the national security interests

of the United States. These satellites, which can penetrate hostile

and denied areas with no risk to life and rapidly deliver uniquely

valuable information, have allowed a succession of Presidents to

make informed decisions based on critical intelligence and to respond

appropriately to major crises, threats and challenges to U.S. interests.

Without them, America's history and the world's could have been

dramatically different.

For 40 years,

the NRO has pioneered technical marvels in support of space reconnaissance.

Quite literally, the NRO's achievements in space have provided the

nation its "eyes and ears" for: monitoring the proliferation

of weapons of mass destruction and compliance with arms control

agreements; tracking international terrorists, narcotics traffickers

and others who threaten American lives and interests around the

world; providing operational intelligence and situational awareness

to our armed forces in situations ranging from combat to peacekeeping;

and helping to anticipate and cope with disasters, ranging from

wildfires in the American West to volcanic eruptions in the Pacific

to humanitarian crises in the Balkans.

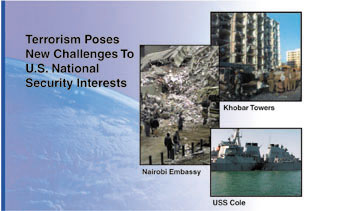

In many ways,

the risks to the security of the United States from potentially

catastrophic acts of terrorism and weapons of mass destruction and

mass disruption are more complex today than those the United States

confronted during the Cold War. The number of extended U.S. military

commitments and other U.S. interests around the globe that require

continuing support is stressing the capacity of NRO reconnaissance

systems and the Intelligence Community to detect critical indications

and warnings of potentially threatening events. Further, the NRO

does more than just build satellites. Integrating all-source intelligence

requires it to produce new technologies. Together, these and other

evolving conditions place an enormous premium on maintaining a strong

space reconnaissance capability.

NRO capabilities

have been available for the past 40 years because President Dwight

Eisenhower and his successors clearly understood the significance

of space reconnaissance to our national security. They had the tenacity

and determination to endure the many risks and failures inherent

in space technology, and they personally directed and sustained

the investment needed for its development. The United States is

far more secure today because of this prior investment, commitment

and level of personal attention.

However, the

clarity of mission and sense of urgency that led past Presidents

and Congresses to invest in the future of space reconnaissance dissipated

with the Cold War's end. The disappearance of a single large threat

has provided a false sense of security, diverting our attention

from national security issues and, for the NRO, resulting in under-investment.

Unfortunately, this false sense of security has been accompanied

by a particularly ill-timed lack of policy direction to the NRO

from senior officials. This comes at a time when the array of threats

facing the United States has never been more complex and the demands

on the NRO from new customers have never been more intense.

Users of the

intelligence provided by the NRO's satellites have long competed

for priority. But now, the number of these customers has expanded

dramatically. Advances in military technology have led military

customers to develop a voracious appetite for NRO data. At the same

time, non-military customers increasingly demand more information

from the NRO regarding a broad array of intelligence targets. Also,

dynamic changes throughout the Intelligence Community and enormous

growth in information technology are significantly affecting the

NRO. In the absence of additional resources, the NRO is being stretched

thin trying to meet all its customers' essential requirements.

We believe the

American people may assume that space-based intelligence collection

matters less today than it did during the Cold War at a time when,

paradoxically, the demand for the NRO's data has never been greater.

This Report

stresses the need for decisive leadership at the highest levels

of the U.S. Government in developing and executing a comprehensive

and overarching national security policy and strategy that sets

the direction and priorities for the NRO. Ensuring that the

United States does not lose its technological "eyes and ears"

will require the personal attention and direction of the President,

the Secretary of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence

(DCI).

There has been

and will continue to be understandably heavy pressure to maintain

current, aging capabilities rather than to bear the expense of riskier

modernization and development of advanced technologies. Without

bold and sustained leadership, the United States could find itself

"deaf and blind" and increasingly vulnerable to any of

the potentially devastating threats it may face in the next ten

to twenty years.

Overall

Finding and Conclusion

The

Commission concludes that the National Reconnaissance Office demands

the personal attention of the President of the United States, the

Secretary of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence. It

must remain a strong, separate activity, with a focus on innovation,

within the Intelligence Community and the Department of Defense.

Failure to understand and support the indispensable nature of the

NRO as the source of innovative new space-based intelligence collection

systems will result in significant intelligence failures. These

failures will have a direct influence on strategic choices facing

the nation and will strongly affect the ability of U.S. military

commanders to win decisively on the battlefield.

Summary

of the Commission's Key Findings and Recommendations

Changing NRO Responsibilities

Throughout its history, the NRO has met the challenge of providing

innovative, space-based reconnaissance solutions to difficult

intelligence problems. Since the earliest days of the Corona spy

satellites, when the NRO developed the first space-based photographic

capability, the NRO has remained on the leading edge of space

technology.

The NRO's

success at innovation has been made possible by:

-

involvement by the President and the joint Secretary of Defense-DCI

responsibility for management of the NRO;

-

its status, under the NRO Director, as the only Government

office responsible for developing space reconnaissance systems;

-

staffing by Department of Defense (DoD) and Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA) personnel;

-

adequate funding with sensible reserves;

-

a high degree of secrecy;

-

technological depth focused on developing space reconnaissance

solutions to difficult intelligence problems; and

-

experienced program managers empowered to make decisions and

requiring minimal oversight.

It is important

that the NRO remain focused on its primary space-based reconnaissance

mission. It is equally important that both the NRO's special talents

and the institutional foundation that has facilitated its success

for four decades be carefully preserved.

The NRO has

often approached its mission from an "end-to-end" perspective.

The NRO did more than build satellites to collect information.

It also built capabilities to task the satellites, process the

data collected and disseminate the information to its primary

users. By taking this comprehensive approach, the NRO was able

to develop high-performance satellite systems that better served

its customers' needs.

However,

the structure of the Intelligence Community has changed since

the NRO's earliest days. New organizations exist and many intelligence

functions are now shared. Tasking, processing, exploitation, and

dissemination (TPED) functions are dispersed throughout the Intelligence

Community. In this changed environment, some officials are concerned

that the NRO is duplicating efforts in areas for which other agencies

now have primary responsibility.

The National

Imagery and Mapping Agency, the National Security Agency, and

the Central MASINT [measurement and signature intelligence] Organization

bear primary responsibility for managing the tasking and dissemination

of information collected by NRO satellites, and processing of

intelligence data is shared among these same organizations. At

the same time, the NRO is responsible for ensuring its satellites

operate efficiently and effectively.

In developing

TPED processes in connection with its own systems, the NRO often

has developed innovative solutions to difficult problems in these

areas. To encourage development of creative solutions in the future,

the Commission believes it important that the delineation of responsibilities

for TPED be carefully and regularly evaluated by senior officials

in order to avoid duplication and enhance Intelligence Community

efficiency and effectiveness.

The Secretary

of Defense and Director of Central Intelligence must direct that

the NRO mission be updated and focused as a first priority on

the development, acquisition and operation of highly advanced

technology for space reconnaissance systems and supporting space-related

intelligence activities, in accordance with current law.

The Secretary

of Defense and Director of Central Intelligence should determine

the proper roles for the NRO, National Security Agency, National

Imagery and Mapping Agency, and Central MASINT Organization in

tasking, processing, exploitation, and dissemination activities.

NRO

Technological Innovation

Over time, the NRO has gained a well-deserved reputation as the

preeminent research, development and acquisition (RD&A) organization

in the Intelligence Community and DoD. As a result of changes

in recent years, however, some claim the NRO has lost its streamlined

acquisition and integration capability and its ability to develop

and apply new technologies rapidly.

The Commission

believes NRO leadership is doing its best in emphasizing RD&A;

in accepting new ideas, concepts and base technologies from any

source; and in applying "leap ahead" and "revolutionary"

technologies to its work. The NRO's focus is, as it should be,

on technologies that will enhance, improve, or fundamentally change

the way in which the United States engages in space-based reconnaissance.

The NRO's

development and application of new technologies has sometimes

been limited by a resource-constrained budget process. The budget

process is not well suited to making judgments about the value

of developing new technology. In these circumstances, recommendations

from the Intelligence Community, Office of Management and Budget,

or other budget staffs regarding whether or not to provide resources

for an NRO program should not be made without the benefit of clear

guidance from senior officials based upon the value of the technology

being developed in the NRO program. Decision-makers must ensure

that they are provided personally with the technical understanding

needed to assure that the decisions they make with regard to NRO

technology innovation efforts are informed decisions.

The President

of the United States, the Secretary of Defense and the Director

of Central Intelligence must pay close attention to the level

of funding and support for the NRO Director's research, development

and acquisition effort.

The Secretary

of Defense and Director of Central Intelligence should ensure

common understanding of the NRO's current and future capabilities

and the application of its technology to satisfy the needs of

its mission partners and customers.

Office

of Space Reconnaissance

From its beginning, NRO success has been based upon several special

attributes. Among these have been: the personal attention of the

President; a close partnership between the Secretary of Defense

and the Director of Central Intelligence; a single Director and

organization with technological expertise focused on space reconnaissance

on behalf of the DoD and CIA; experienced CIA and military personnel

and program managers; and a strong cloak of secrecy surrounding

its activities.

Over time,

these attributes have eroded. The Commission observes that one

of the most important changes is that implementation of the Secretary

of Defense-DCI partnership has been delegated to lower-level officials.

Also, the NRO Director is caught in the middle of an intense debate

regarding whether strategic or tactical intelligence requirements

should have higher priority in NRO satellite reconnaissance programs.

The personnel practices of other organizations are discouraging

NRO personnel from seeking repetitive assignments within the NRO.

The NRO has become a publicly acknowledged organization that openly

announces many of its new program initiatives.

These changes

are a direct response to the circumstances described earlier.

While many of the changes have been warranted, they have had a

limiting effect on the NRO's ability to attack the most difficult

intelligence problems quickly with the most advanced space reconnaissance

technology. Perhaps more importantly, they have weakened the foundation

of congressional and presidential support upon which the NRO's

success has been built.

The Commission

believes structural change is needed. A new office should be established

that, by recapturing and operating under the NRO's original attributes,

will respond more effectively to technological challenges in space

reconnaissance. The Commission suggests this office be called

the Office of Space Reconnaissance.

This would

require that the Secretary of Defense grant this Office special

exemptions from standard DoD acquisition regulations. It would

rely heavily upon the DCI's special statutory authorities for

procurement. It would be under the direction of the NRO Director,

but would operate in secure facilities separated from NRO activities.

It would create and defend a separate budget element within the

National Foreign Intelligence Program and have its own security

compartment. It would have a small CIA and military staff and

senior and experienced program managers, and would also rely heavily

upon the creativity of the contractor community for its work.

It would respond, through a special Executive Committee, to direction

from the President, the Secretary of Defense and the DCI. The

new Office would attack the most difficult intelligence problems

by providing advanced technology that will lead to frequent, assured,

global access to protect U.S. national security interests.

The Commission

emphasizes that creation of the Office of Space Reconnaissance

does not diminish the fundamental importance of the NRO and its

mission. Under this approach, the NRO would continue to serve

the broad and growing strategic and tactical customer base. It

would also continue to evaluate and apply leading edge technology

to meet the needs of those customers, and to confront and overcome

the intelligence challenges facing the Intelligence Community

and DoD.

The Secretary

of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence should establish

a new Office of Space Reconnaissance under the direction of the

Director of the NRO. The Office should have special acquisition

authorities, be staffed by experienced military and CIA personnel,

have a budget separate from other agencies and activities within

the National Foreign Intelligence Program, be protected by a special

security compartment, and operate under the personal direction

of the President, Secretary of Defense and Director of Central

Intelligence.

The

Secretary of Defense-Director of Central Intelligence Relationship

The NRO serves both the Secretary of Defense and the DCI. In the

NRO's early days, several agreements established the relationship

between the Secretary of Defense and the DCI. Today, the NRO is

operating under agreements between these two officials, all of

which are at least thirty-five years old.

Space has

proven to be the most effective means for gaining frequent, assured

access to denied areas on a global basis. The NRO's history is

filled with successes in answering intelligence questions asked

by military and civilian leaders who faced difficult national

security challenges.

The Commission

evaluated the desirability of recommending the creation of an

"NRO statute." Such a law could firmly secure the NRO's

position in the national security community. After debate, the

Commission concluded that congressional action in this regard

could make the situation worse, rather than better. It believes

senior level Executive Branch attention should be sufficient at

this time.

Therefore,

in order to achieve the most cost-effective means for gaining

global access to denied areas, the President, Secretary of Defense

and Director of Central Intelligence must work closely together

to direct the NRO's efforts.

The President

must take direct responsibility to ensure that the Secretary of

Defense and Director of Central Intelligence relationship regarding

the management of the NRO is functioning effectively.

Balanced

Response to Customer Demands

Developments in information technology have both benefited and

challenged the NRO. Because of these developments, information

the NRO collects is more readily available to tactical military

commanders and plays a significant role in gaining information

dominance. As a result, military theater and tactical commanders

increasingly expect and demand NRO support.

The NRO's

global presence also continues to provide senior strategic decision-makers

with information essential to their understanding of the international

environment. As has been the case since its earliest days, the

NRO's satellites acquire information other intelligence sources

are unable to provide. Its satellites furnish a unilateral, low

profile, zero risk, and secure means of collecting highly sensitive

intelligence. They support diplomacy, prevent war, aid the war

on drugs, monitor the development of weapons of mass destruction,

and help thwart terrorist activities.

Customer

demands, however, exceed the NRO's capabilities. As is the case

with all U.S. national security activities today, the NRO's budget

is constrained and it competes for resources with other intelligence

agencies that are also facing new challenges created by the changing

threat and the explosion in information technology.

Because it

responds to both the Secretary of Defense and the DCI, the NRO

frequently is caught between the competing requirements of both

DoD and non-DoD customers, all of whom expect to be satisfied

by NRO systems. With its systems over-taxed and unable to answer

all demands, yet attempting to be "all things to all agencies,"

the NRO often bears the brunt of criticism from all sides.

Because of

these pressures, the NRO is a strong and persistent advocate for

greater resources in an era of limited Intelligence Community

budgets. However, the Commission's recommendations are focused

on balancing competing needs because it is not possible simply

to "buy" a way out of the problem.

The Secretary

of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence must work

closely together to ensure that proper attention is focused on

achieving the appropriate balance between strategic and tactical

requirements for NRO systems, present and future.

Defense

Space Reconnaissance Program

In response to the long-standing need for the NRO to develop space

reconnaissance assets that respond to both strategic and tactical

requirements, the Defense Support Project Office was established

in 1981. The NRO Director also served as the Director of that

Office.

The Office

was responsible for the annual development of the Defense Reconnaissance

Support Program (DRSP) contained in the DoD Tactical Intelligence

and Related Activities (TIARA) Program. DRSP funds generally were

used to pay for NRO activities that were necessary to satisfy

military-unique space reconnaissance requirements.

In 1994,

DRSP funding was substantially reduced. Responsibility for satellite

acquisition and infrastructure costs was shifted to the National

Reconnaissance Program. The name of the DRSP was changed to the

Defense Space Reconnaissance Program (DSRP), which became focused

on educating military customers on how to use NRO systems more

effectively. These changes ended DoD's direct funding of NRO reconnaissance

systems and took place even as DoD's appetite for NRO information

was growing substantially in response to the military's experiences

in the Gulf War.

The debate

over which customers should have higher priority for NRO space

reconnaissance capabilities is partly the result of the need to

allocate scarce funds. Experience since 1994 suggests that certain

programs to support tactical military requirements have had increasing

difficulty competing for funds within the National Reconnaissance

Program (NRP). This is because NRP spending to address those requirements

consumes resources appropriated to the National Foreign Intelligence

Program (NFIP). Some believe those requirements should be supported

by intelligence funding taken from the DoD budget. Thus, the debate

often is not about whether the NRO should undertake an activity,

but rather how the NRO will fund it.

The Commission

believes it is time to re-establish funds within the DoD budget

that will pay for the acquisition of systems and sensors designed

to support tactical commanders. If certain NRO acquisition decisions

were made part of a DSRP budget process in this way, the military's

Unified Commands would be directly involved in setting priorities

for future space reconnaissance systems. Further, budget pressures

on the NFIP would be reduced by such direct DoD funding for NRO

systems.

The Secretary

of Defense, in consultation with the Director of Central Intelligence,

should re-establish the Defense Space Reconnaissance Program as

a means of funding tactical military requirements for NRO systems

and architectures.

Increased

Resource and Budgetary Flexibility

Budget constraints affect the entire National Foreign Intelligence

Program (NFIP). As each Intelligence Community activity strives

to meet new challenges, it competes with other NFIP activities

that have strong claims for resources. The dynamic budgetary environment

and the diffuse national security threats require flexible measures

for shifting resources to meet rapidly changing priorities.

The Director

of Central Intelligence is responsible, in consultation with the

Secretary of Defense, for the creation of the NFIP. This clear

responsibility, however, is not matched by a similar responsibility

for actual expenditure of the funds after they have been authorized

and appropriated to the NFIP by Congress. Under current law, the

Director may not shift such funds between intelligence activities

if the affected Secretary or department head objects.

The Commission's

principal concern is the potential limit that this provision of

current law places on the DCI's ability to shift resources to

match quickly changing priorities in a dynamic intelligence environment.

While the Commission recognizes this issue extends beyond the

NRO, it believes it is of such significance for the NRO that a

recommendation to remedy the situation is warranted.

The Director

of Central Intelligence should be granted greater latitude to

redirect funds among intelligence collection activities and agencies

in order to respond most effectively to the specific types of

issues that arise in NRO programs.

NRO

Technical Expertise

The NRO's historic success is directly attributable to the high

quality and creativity of its DoD, CIA and contractor workforce.

Until the recent past, many military and civilian Government personnel

served the majority of their careers as part of the NRO. Some

never returned to their parent organizations for any appreciable

length of time. This allowed a highly skilled cadre of personnel

to advance within the NRO structure, gaining relevant experience

in various positions of greater responsibility as they rose in

rank.

New personnel

assignment practices adopted by other organizations, such as the

Air Force, have had the effect of limiting the tenure of personnel

assignments to the NRO. There is a resulting concern that the

NRO could lose its ability to sustain the cadre of highly-skilled

and experienced personnel it needs to guarantee mission success

because rotational assignments back to their parent organizations

appear to be a requirement for career advancement. In some cases,

this cadre of personnel is prevented from obtaining equivalent

broad space-related experience during these rotational assignments.

While it is understandable that a parent organization may want

to exploit the special skills its personnel develop in the NRO,

the cost to NRO space reconnaissance programs may be greater than

the value of broader experience to these other organizations.

The Commission

believes there is a compelling need for a separate NRO career

path and assignment policy that provides an opportunity for selected

highly trained engineers, acquisition professionals and operations

specialists to be assigned to the NRO on a long-term basis and

progress through a broad range of NRO positions. The technical

complexity of NRO systems is unique, and it requires the continuity

of a dedicated cadre. The Commission believes the high quality

and creativity of the NRO's military, CIA and contractor workforce

must be sustained.

The Secretary

of Defense and the Director of Central Intelligence should jointly

establish NRO career paths to ensure that a highly skilled and

experienced NRO workforce is continued and sustained.

Increased

Launch Program Risks

The U.S. Government's national security space program is proceeding

along several parallel paths. At the same time the NRO is embarking

upon new satellite acquisition programs, the Air Force is transitioning

its launch program to the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV)

family of space launch vehicles. The NRO relies upon the Air Force

to provide its launch capability. Thus, all the new NRO satellites

are to be launched on the new EELV.

Historically,

spacecraft and launch vehicle development programs have failed

to meet original estimated delivery dates. In addition, the spacecraft

and launch vehicles that initially emerge from new developmental

programs carry a significantly increased risk of unforeseen difficulties.

In the past, the effects of delays and launch failures could be

mitigated because robust satellite capabilities were on orbit

or sufficient launch vehicles were available as a back-up. Today,

the fragility of the satellite and launch vehicle architectures

offers no margin for error.

The Commission

is alarmed that there appears to be no comprehensive strategy

to address the increased risks presented by simultaneously developing

new reconnaissance satellites and launch vehicles. This contributes

to an already uncertain situation where new satellites will be

launched on new boosters.

The NRO

Director, with the support of the Air Force Materiel Command and

Space and Missile Systems Center, should develop a contingency

plan for each NRO program or set of programs. These plans should

describe risks, contingency options and failure mitigation plans

to minimize satellite system problems that might result from satellite

or launch vehicle failures.

Commercial

Satellite Imagery

Rapid technological developments in the commercial space industry

are yielding capabilities that could usefully supplement U.S.

Government-developed space reconnaissance systems. Although a

National Space Policy exists that promotes the use of the products

and services of the U.S. commercial space industry, the Commission

did not find any executable plan, budget, or strategy that promotes

the use of commercial satellite imagery.

The Commission

supports Government purchases of one meter and one-half meter

resolution commercial imagery, which can meet a large percentage

of U.S. Government imagery requirements. The Commission believes

there is a need for an overall assessment--independent of the

NRO--of the utility of commercial technologies to supplement traditional

NRO missions.

NRO imagery

is provided to Government users "free of charge," while

in many cases those same users have to use current funds to pay

for commercial imagery. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that

they find commercial imagery less attractive even as their demand

constantly increases for the "free" NRO imagery. If

commercial imagery is to achieve its potential to reduce the demands

on NRO systems, decisions regarding the use of commercial imagery

must be made on an even footing with decisions about the use of

NRO-provided imagery.

The Presidential

Decision Directive (PDD-23) that establishes U.S. policy regarding

exports of remote sensing technology and data may be inhibiting

effective U.S. responses to proliferation of such technology internationally.

The Commission urges the next Administration to re-examine this

Directive in light of recent experience.

A clear

national strategy that takes full advantage of the capabilities

of the U.S. commercial satellite imagery industry must be developed

by the President, Secretary of Defense and Director of Central

Intelligence.

The strategy

must contain a realistic execution plan--with timelines, a commitment

of the necessary resources and sound estimates of future funding

levels.

NRO

Airborne Reconnaissance Responsibilities

Until the early 1990's, the NRO also developed high altitude airborne

reconnaissance systems, such as the SR-71 aircraft. In fact, a

1964 DoD Directive that remains in effect assigns responsibility

for strategic airborne reconnaissance to the NRO.

Too often,

space reconnaissance and strategic airborne reconnaissance are

viewed as mutually exclusive capabilities. In fact, they are quite

complementary and contribute unique support to a tiered concept

of intelligence collection.

To achieve

and maintain a proper balance between space-based and airborne

reconnaissance, the Commission believes the NRO needs to restore

its interest in airborne platforms and participate in engineering

studies to select the proper platform for the required mission.

The NRO

should participate jointly with other agencies and departments

in strategic airborne reconnaissance development. Specifically,

the NRO should supply system engineering capabilities and transfer

space system technologies to airborne applications.