South Asia

In 1999 the locus of terrorism directed against the United States continued

to shift from the Middle East to South Asia. The Taliban continued to provide

safehaven for international terrorists, particularly Usama Bin Ladin and his

network, in the portions of Afghanistan they controlled. Despite the serious

and ongoing dialogue between the Taliban and the United States, Taliban leadership

has refused to comply with a unanimously adopted UNSC resolution demanding that

they turn Bin Ladin over to a country where he can be brought to justice.

The United States made repeated requests to Islamabad to end support for elements

harboring and training terrorists in Afghanistan and urged the Government of

Pakistan to close certain Pakistani religious schools that serve as conduits

for terrorism. Credible reports also continued to indicate official Pakistani

support for Kashmiri militant groups, such as the Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM),

that engaged in terrorism.

In Sri Lanka the government continued its protracted conflict with the Liberation

Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

Afghanistan

Islamist extremists from around the world--including North America; Europe;

Africa; the Middle East; and Central, South, and Southeast Asia--continued to

use Afghanistan as a training ground and base of operations for their worldwide

terrorist activities in 1999. The Taliban, which controlled most Afghan territory,

permitted the operation of training and indoctrination facilities for non-Afghans

and provided logistic support to members of various terrorist organizations

and mujahidin, including those waging jihads in Chechnya, Lebanon,

Kosovo, Kashmir, and elsewhere.

Throughout the year, the Taliban continued to host Usama Bin Ladin--indicted

in November 1998 for the bombings of two US Embassies in East Africa--despite

US and UN sanctions, a unanimously adopted United Security Council resolution,

and other international pressure to deliver him to stand trial in the United

States or a third country. The United States repeatedly made clear to the Taliban

that they will be held responsible for any terrorist acts undertaken by Bin

Ladin while he is in their territory.

In early December, Jordanian authorities arrested members of a cell linked

to Bin Ladin's al-Qaida organization--some of whom had undergone explosives

and weapons training in Afghanistan--who were planning terrorist operations

against Western tourists visiting holy sites in Jordan over the millennium holiday.

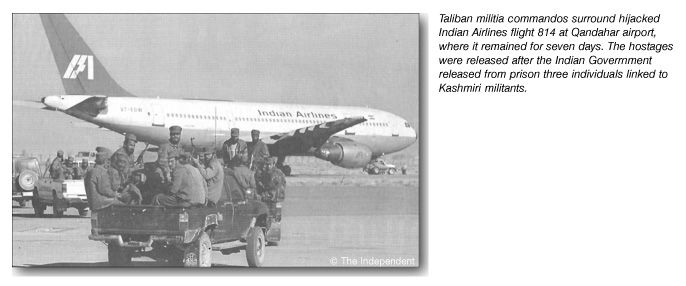

On 25 December the Taliban permitted hijacked Indian Airlines flight 814 to

land at Qandahar airport after refusing it permission to land the previous day.

The hijacking ended on 31 December when the Indian Government released from

prison three individuals linked to Kashmiri militant groups in return for the

release of the passengers aboard the aircraft. The hijackers, who had murdered

one of the Indian passengers during the course of the incident, were allowed

to go free. The Taliban stated that the hijackers, who reportedly are Kashmiri

militants, would leave Afghanistan even if they were unable to obtain political

asylum from another country. Their whereabouts remained unknown at yearend.

India

Security problems persisted in India in 1999 from ongoing insurgencies in

Kashmir and the northeast. Kashmiri militant groups continued to attack Indian

Government, military, and civilian targets in India-held Kashmir and elsewhere

in the country. The militants probably bombed a passenger train traveling from

Kashmir to New Delhi on 12 November, killing 13 persons and wounding 50. Militant

groups operating in Kashmir also mounted a grenade attack against a wedding

in Srinagar, Kashmir's summer capital, which wounded at least 20 wedding participants.

In the northeast, Nagaland's Chief Minister escaped injury on 29 November when

a local extremist group attacked his convoy. The attack killed two of his guards

and injured several others.

The Indian Government took a number of steps against terrorism at home and

abroad. In August the Indian cabinet ratified the international convention for

the suppression of terrorist bombings. New Delhi also introduced a convention

on the suppression of terrorism at the UN General Assembly meeting. Indian law

enforcement authorities continued to cooperate with US officials to ascertain

the fate of four Western hostages--including one US citizen-- kidnapped in 1995

in Indian Kashmir, although the hostages' whereabouts remained unknown. New

Delhi announced in November 1999 the establishment of a US-India Counterterrorism

Working Group, which aimed to enhance efforts to counter international terrorism

worldwide.

Pakistan

Pakistan is one of only three countries that maintains formal diplomatic

relations with--and one of several that supported--Afghanistan's Taliban, which

permitted many known terrorists to reside and operate in its territory. The

United States repeatedly has asked Islamabad to end support to elements that

conduct terrorist training in Afghanistan, to interdict travel of militants

to and from camps in Afghanistan, to prevent militant groups from acquiring

weapons, and to block financial and logistic support to camps in Afghanistan.

In addition, the United States has urged Islamabad to close certain madrasses,

or "religious" schools, that actually serve as conduits for terrorism.

Credible reports continued to indicate official Pakistani support for Kashmiri

militant groups that engage in terrorism, such as the Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM).

The hijackers of the Air India flight reportedly belong to one of these militant

groups. One of the HUM leaders, Maulana Masood Azhar, was freed from an Indian

prison in exchange for the hostages on the aircraft in the Air India hijacking

in December and has since returned to Pakistan.

Kashmiri extremist groups continued to operate in Pakistan, raising funds and

recruiting new cadre. The groups were responsible for numerous terrorist attacks

in 1999 against civilian targets in India-held Kashmir and elsewhere in India.

Pakistani officials from both Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif's government and,

after his removal by the military, General Pervez Musharraf's regime publicly

stated that Pakistan provided diplomatic, political, and moral support for "freedom

fighters" in Kashmir--including the terrorist group Harakat ul-Mujahidin--but

denied providing the militants training or materiel.

On 12 November, shortly after the United Nations authorized sanctions against

the Taliban, but before the sanctions were implemented, unidentified terrorists

launched a coordinated rocket attack against the US Embassy, the American center,

and possibly UN offices in Islamabad. The attacks caused no fatalities but injured

a guard and damaged US facilities.

Sectarian and political violence remained a problem in 1999 as Sunni and Shia

extremists conducted attacks against each other, primarily in Punjab Province,

and as rival wings of an ethnic party feuded in Karachi. Pakistan experienced

a particularly strong wave of such attacks across the country in August and

September. Domestic violence dropped significantly after the military coup on

12 October.

In the wake of US diplomatic intervention to end the Kargil conflict that broke

out in April between Pakistan and India, several Pakistani and Kashmiri extremist

groups stridently denounced US interference and activities. Jamiat-e-Ulema Islami

leaders, for example, reacted to US diplomacy in the region by harshly and publicly

berating US efforts to bring wanted terrorist Usama Bin Ladin, who is based

in Afghanistan, to justice for his role in the 1998 US Embassy bombings in Nairobi

and Dar es Salaam. The imposition of US sanctions on 14 November against Afghanistan's

Taliban for its continued support for Bin Ladin drew a similar response.

Sri Lanka

The separatist group Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), which the

United States has designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization, maintained a

high level of violence in 1999, conducting numerous attacks on government, police,

civilian, and military targets. President Chandrika Kumaratunga narrowly escaped

an LTTE assassination attempt in December. The group's suicide bombers assassinated

moderate Tamil politician Dr. Neelan Tiruchelvam in July and killed 34 bystanders

at election rallies in December. LTTE gunmen murdered a Tamil Member of Parliament

from Jaffna representing the Eelam People's Democratic Party and the leader

of a Tamil military unit supporting the Sri Lankan Army.

Over the year, LTTE attacks against police officers killed 50 and wounded 77.

Bombings of buses, trains, and bus terminals in March, April, and September

killed four persons and injured more than 80, and Sri Lankan authorities attributed

several bombings of telecommunications and power facilities to the LTTE. In

July an LTTE suicide diver bombed a civilian passenger ferry while it was in

Trincomalee port, and the group's Sea Tigers naval wing attacked a Chinese vessel

that had come too close to the Sri Lankan coastline. The LTTE allegedly massacred

more than 50 civilians in September, apparently retaliating against a Sri Lankan

Air Force bombing that killed 21 Tamil civilians. The LTTE is suspected in the

shooting death in Jaffna of a regional military commander for the progovernment

People's Liberation Organization of Tamil Eelam (PLOTE) and may be responsible

for bombings at a PLOTE office and a camp in Vavuniya that killed three and

injured seven.

LTTE activity against the Sri Lankan Government centered on the continuing

war in the north. The Sri Lankan military's offensive to open and secure a ground

supply route through LTTE-held territory suffered a major defeat when the LTTE

fought a series of intense battles in early November and regained control of

nearly all land the government had captured in the past two years. The battles

resulted in thousands of casualties on both sides.

There were no confirmed cases of LTTE or other terrorist groups targeting US

citizens or businesses in Sri Lanka in 1999. Nonetheless, the Sri Lankan Government

was quick to cooperate with US requests to enhance security for US personnel

and facilities and cooperated fully with US officials investigating possible

violations of US law by international terrorist organizations. Battlefield requirements

forced Sri Lankan security forces to cancel their participation in a senior

crisis management seminar under the Department of State's Anti-Terrorism Assistance

Program in 1999.

East Asia

The scorecard for terrorism in East Asian nations in 1999 was mixed, with

some countries enjoying significant improvements and others suffering an upswing

of attacks. The most positive development occurred in Cambodia, where the Khmer

Rouge's once-deadly threat all but ended with the group's dissolution as a viable

terrorist organization.

Political disagreements frequently were the inspiration for terrorist acts

in East Asia. In Indonesia the overwhelming East Timor vote in favor of independence

provoked violent reprisals by militias on that island as well as in Jakarta.

In addition, a US-owned oil company's facilities were targeted in Aceh, Sumatra.

Japan's Aum Shinrikyo, which was redesignated a Foreign Terrorist Organization

(FTO) in October, admitted to and apologized for its sarin attack on Tokyo's

subway in 1995. Facing increasing public pressure, the Japanese Government instituted

legal restrictions on the group. In response, the Aum announced plans to suspend

its public activities as of 1 October. The Government of Japan also continued

to seek the extradition of Japanese Red Army (JRA) members from Lebanon and

Thailand.

Several groups in the Philippines engaged in or threatened violent acts. The

Communist Party of the Philippines New People's Army (CPP/NPA) broke off peace

talks in June in retaliation for the government's Visiting Forces Agreement

with the United States that provides for joint military training exercises.

While the CPP/NPA only threatened to attack US forces, it targeted Philippine

security forces in numerous incidents. Both the separatist group Moro Islamic

Liberation Front (MILF), as well as the redesignated FTO Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG),

were blamed for various attacks and kidnappings for ransom.

In Thailand five prodemocracy students staged a takeover on 1 October of the

Burmese Embassy in Bangkok, holding 32 persons hostage, including one U.S. citizen.

The incident ended without violence.

Cambodia

The Khmer Rouge (KR) insurgency ended in 1999 following a series of defections,

military defeats, and the capture of group leader Ta Mok in March. The KR did

not conduct international terrorism in 1999, and the US Government removed it

from the list of designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations. Former KR members,

however, still posed an isolated threat in remote areas of the country. Suspected

ex-KR soldiers, for example, attacked a hill tribe in northeastern Cambodia

in July in an apparent criminal incident.

The Cambodian Government worked on drafting a law for the United Nations to

assist in establishing a court to try former KR members who were senior leaders

of the regime responsible for the deaths of up to 2 million persons in Cambodia

during the 1975-79 period. A former KR official warned in September, however,

that unrest would resurface if the Cambodian Government put the KR on trial.

Indonesia

The ballot results on 30 August favoring East Timor's independence sparked

prointegration militias--armed East Timorese favoring unity with Indonesia--to

mount a violent campaign throughout September against proindependence supporters.

A number of militia members accused the United Nations of manipulating the ballot

results, leading some militia units to seek foreign targets in the province.

Incidents included the serious wounding of a US police officer working for the

UN Assistance Mission to East Timor, an attack against the Australian Ambassador's

vehicle, and an assault against the Australian Consulate in Dili, East Timor's

capital. Militiamen also allegedly killed a Dutch Financial Times reporter

in a Dili suburb on 21 September after his motorcycle driver tried to flee six

armed men. In a separate incident the same day, prointegrationists ambushed

a British journalist and a US citizen photographer in Bacau, east of Dili, but

Australian troops later rescued the two.

A prointegration militia leader told former Indonesian Armed Forces Commander

General Wiranto in early September that he would have no regrets about killing

nongovernmental organization or UN persons who supported the proindependence

side. Militia threats and attacks against foreigners, however, dropped dramatically

after late September, when the situation began to stabilize.

Indonesian nationalists, mostly in Jakarta, responded to the referendum and

the subsequent deployment of the International Force for East Timor with protests

and low-level violence against perceived interference in their country's internal

affairs. In late September the Australian Embassy in Jakarta was the target

of almost daily demonstrations that included petrol bombs and stone throwing.

Gunmen fired shots at the Australian Embassy on three separate occasions in

apparent anger over Canberra's role in the international peacekeeping mission.

In addition, unidentified assailants threw Molotov cocktails at the Australian

International School in Jakarta on 4 October, but no injuries resulted. As of

25 October, pursuant to a UN Security Council resolution, the United Nations

Transitional Administration in East Timor assumed all legislative and executive

authority in East Timor and responsibility for the administration of justice.

Separatist violence flared in other parts of the country, particularly in Aceh,

Sumatra, where the Free Aceh Movement and its sympathizers clashed with Indonesian

security forces throughout the year. The separatists, demanding a referendum

on Aceh independence, primarily attacked Indonesian targets, but US interests

in the province suffered collateral damage. Unidentified assailants, for example,

fired at a Mobil Oil bus and burned a Mobil-operated community health clinic

on two separate occasions in late September. Free Papua Movement separatists

located in Irian Jaya did not attack foreign interests but conducted some violent

protests and low-level attacks against Indonesian targets in 1999.

Several small-scale bombings of undetermined motivation also occurred in Indonesia

during the year, including the attack against the National Istiqlal Mosque in

Jakarta that injured six persons on 19 April. In addition, unidentified assailants

conducted other bombings that injured several Indonesians in Jakarta's city

center following the presidential election in October.

Japan

Aum Shinrikyo, the Japanese cult that conducted the sarin attack on the Tokyo

subway system in March 1995, continued efforts to rebuild itself in 1999. The

group's recruitment, training, fundraising--especially a computer business that

generated more than $50 million--and property acquisition, however, provoked

numerous police raids and an extensive public backlash that included protests

and citizen-led efforts to monitor and barricade Aum facilities.

In an effort to alleviate public pressure and criticism, Aum leaders in late

September announced the group would suspend its public activities for an indeterminate

period beginning 1 October. The cult openly pledged to close its branch offices,

discontinue public gatherings, cease distribution of propaganda, shut down most

of its Internet Web site, and halt property purchases beyond that required to

provide adequate housing for existing members. The cult also said it would stop

using the name "Aum Shinrikyo." On 1 December, Aum leaders admitted

the cult conducted the sarin attack and other crimes--which they had denied

previously--and apologized publicly for the acts. The cult made its first compensation

payment to victims' families in late December.

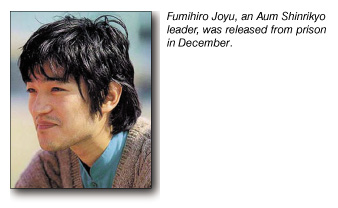

Japanese courts sentenced one Aum member to death and another to life in prison

for the subway attack, while trials for other members involved in the attack

remain ongoing. The prosecution of cult founder Shoko Asahara continued at a

sluggish pace, and a verdict remained years away. Japanese authorities remained

concerned over the release in late December of popular former cult spokesman

Fumihiro Joyu--who served a three-and-a-half-year jail sentence for perjury--and

his expected return to the cult as a senior leader. The Japanese parliament

in December passed legislation strengthening government authority to crack down

on groups resembling the Aum and allowing the government to confiscate funds

from the group to compensate victims. The Public Security Investigation Agency

stated that it would again seek to outlaw the Aum under the Anti-Subversive

Activities Law. Separately, the Japanese Government continued to seek the extradition

of members of the Japanese Red Army (JRA) from Lebanon and Thailand.

Philippines

The Communist Party of the Philippines New People's Army (CPP/NPA) broke

off peace talks with the Philippine Government in June after the ratification

of the U.S.-Philippine Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA), which provides a legal

framework for joint military training exercises between Philippine and US armed

forces. The CPP/NPA continued to oppose a U.S. military presence in the country

and claimed that the VFA violates the nation's sovereignty. Communist insurgents

did not target U.S. interests during the year, but a Communist member told the

press in May that guerrillas would target U.S. troops taking part in the joint

exercises. Press reporting in September alleged CPP/ NPA plans to target US

Embassy personnel at an unspecified time.

The CPP/NPA continued to target Philippine security forces in 1999. The organization

conducted several ambushes and abductions against Philippine military and police

elements in rural areas throughout the country. The CPP/NPA released most of

its hostages unharmed by late April but still was holding Philippine Army Major

Noel Buan and Philippine Police Official Abelardo Martin at yearend.

The Alex Boncayao Brigade (ABB)--a breakaway CPP/NPA faction--claimed responsibility

for a rifle grenade attack on 2 December against Shell Oil's headquarters in

Manila that injured a security guard. The attack apparently protested an increase

in oil prices.

Islamist extremists also remained active in the southern Philippines, engaging

in sporadic clashes with Philippine Armed Forces and conducting low-level attacks

and abductions against civilian targets. The groups did not attack US interests

in 1999, however. The Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)--redesignated in 1999 as a Foreign

Terrorist Organization--in June abducted two Belgians and held them captive

for five days before releasing them unharmed without ransom. The ASG still was

working to fill a leadership void resulting from the death of Abdurajak Abubakar

Janjalani, who was killed in a clash with the Philippine Army on 18 December

1998.

The Philippine Government and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the

largest Philippine Islamist separatist group, marked the opening of peace talks

on 25 October. Nonetheless, both sides continued to engage in low-level clashes.

MILF chief Hashim Salamat told the press in February that the group had received

from Usama Bin Ladin funds that it used to build mosques, health centers, and

schools in depressed Muslim communities.

Distinguishing between political and criminal motivation for many of the terrorist-related

activities in the Philippines was difficult, most notably in the numerous cases

of kidnapping for ransom in the south. Both Communist and Islamist insurgents

sought to extort funds from businesses or other organizations in their operating

areas, often conducting reprisal operations if money was not paid. Philippine

police officials, for example, said that three separate bomb attacks in August

against a bus company in the southern Philippines may have been the work of

extortionists rather than terrorists.

Thailand

Five prodemocracy students armed with AK-47s and grenades seized the Burmese

Embassy in Bangkok and held 32 hostages on 1 October. The hostages included

20 individuals applying for visas, one of whom was a US citizen. The terrorists

demanded that the Burmese Government release all political prisoners in Burma

and recognize the results of a national election held in 1990. No injuries occurred,

and the situation was resolved the next day after the Thai Deputy Foreign Minister

offered himself as a hostage in exchange for the safety of the hostages inside

the Burmese Embassy. The five terrorists and the Deputy Foreign Minister were

taken by helicopter to a remote jungle area on the Thai-Burmese border. The

Burmese fled into the jungle. (At least one and perhaps three of the five were

shot to death by Thai security forces on 25 January 2000 after participating

in the seizure of a Thai provincial hospital.)

Some low-level bombings and hoax bomb threats also occurred in Thailand during

the year, although no US interests suffered damage. Most of the incidents were

directed against Thai interests, including the bombing of the Democratic Party

headquarters in Bangkok on 14 January. Thai authorities suspect that a bomb

found and defused at the construction site of a new post office in the south

on 15 April was planted by members of the separatist New Pattani United Liberation

Organization to avenge government operations against the group.

[end of text]

Report Index

|