e-Prints

e-Prints e-Prints

e-PrintsLoring Wirbel

(719) 481-3793 or (719) 481-3698

[email protected], [email protected]

Mail: P.O. Box 829

Monument, CO 80132

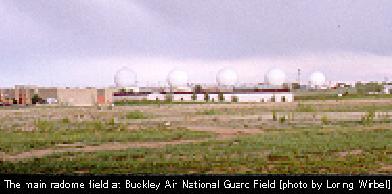

Airplanes taking a north by northwest approach into Denver's new International Airport often will fly over a cluster of eerie white objects in the suburb of Aurora that rival the eclectic nature of DIA's circus-tent architecure. Several 100-foot white domes have sprouted silently on the plains east of Denver, increasing their numbers year by year like mushrooms in a cow pasture.

In the 25 years since Buckley Air National Guard Field became a primary U.S. intelligence base, radomes have been added to the site on Sixth Avenue in Aurora with nary an outcry from the local population. Similar domes now are a regular part of the Federal Aviation Administration's air traffic control network, and there would be little reason for citizens to suspect that the Buckley "golf balls" serve anything other than a benign purpose.

But thanks to a three-year campaign by Colorado Springs-based Citizens for Peace in Space and the American Friends Service Committee in Denver, local citizens are aware that the radomes form the front line of a new direction for the U.S. intelligence community. Buckley is the primary Western Hemisphere facility in a new network of intelligence processing stations called "Regional SIGINT Operations Centers." The base is acknowledged to serve as a processing center for early-warning satellites watching for missile launches, but actually spends the bulk of its time downloading and processing communications intelligence collected by satellites.

This dual role for the secret base is analogous to the two-sided nature of the U.S. intelligence community in the 1990s -- while apparently serving stabilizing interests, agencies are regularly violating civil liberties and enabling destabilizing military doctrines. The intelligence establishment, once dominated by the covert shenanigans of the CIA, is now controlled largely by the high-tech monitoring networks created by the National Security Agency and National Reconnaissance Office.

Most U.S. citizens, including many arms control advocates, assume the missions of NSA and NRO are far more benign than those of the CIA. If the agencies' missions matched the public goals of being the "national technical means of verification" for arms control treaties, this might be true. But three years of probing by CPIS and AFSC, with the help of national organizations like the Federation of American Scientists, have convinced organizers that the agencies' primary post-Cold-War missions are coordinating war-fighting plans, and listening in on civilian and commercial communications.

"The agencies may be secret, but they make no secrets about their belligerent nature," said CPIS director Bill Sulzman. Sulzman, an ex-priest and long-time foe of Star Wars missions in the Colorado Springs area, points to the "Masters of Space" logo proudly displayed by the U.S. Space Command, based at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado Springs.

"NRO officials always talk of providing real-time intelligence for war-fighters," Sulzman said. "They openly admit to expanding their missions to include civilian monitoring, in order to keep their same bloated size now that the U.S.'s primary adversary has withered away. People only maintain myths about technical intelligence because they're not listening to what is being said very openly."

Denver AFSC organizer Tom Rauch sees many similarities between the Rocky Flats nuclear weapons plant and Buckley Field. In both cases, a federal facility grew over a 20-year period under a cloak of intense secrecy, with virtually no input or comprehension by local citizens. Buckley Field opponents in the 1990s, like Rocky Flats opponents in the early 1970s, faced citizens who had a hard time grasping the real problems represented by the facilities. With Buckley, there is the added problem of few health aspects associated with the operations of the intelligence base, unlike the very real dangers of plutonium linked to Rocky Flats. Instead, opponents need to make citizens aware of the doctrinal and civil liberties issues that make Buckley and similar facilities a concrete danger.

Global intelligence expansion by U.S. agencies has a very real impact on Colorado. Buckley is now the major employer in the Denver metro area, with the classified Aerospace Data Facility section of the base responsible for far more jobs than the public Tactical Air Command portion of the base. The Denver Business Journal estimated in April that classified intelligence spending by NSA and NRO in Colorado may exceed $3 billion annually. Support facilities for Buckley include Falcon Air Force Base east of Colorado Springs, which performs intelligence "fusion" missions; Lockheed-Martin's Waterton Canyon plant in southwest Denver, which builds spy satellites and Titan-4 rockets; Peterson Air Force Base, the headquarters of the Space Command; and the aging North American Aerospace Defense Command inside Cheyenne Mountain west of Colorado Springs. Another Air National Guard base outside Greeley, Colorado, is receiving many mobile satellite reconnaissance troops formerly housed at Holloman Air Force Base in New Mexico, part of a mission to make the Colorado Front Range a "center of excellence" for technical intelligence.

Although a continuous series of scandals have kept NSA and NRO in the media spotlight over the last five years, it is not surprising that most citizens remain unaware of their existence, due to the agencies' legacies of secrecy. The ignorance is widespread, despite the fact that both organizations are far larger than the better-known CIA.

NSA was formed by a secret executive order signed by President Harry Truman in November 1952. The agency, which evolved from the small and specialized Armed Forces Security Agency, remained a virtual unknown until 1956, when rumors of its new headquarters at Fort Meade, Md. were carried in press reports of a spy scandal. NSA's acknowledged mission of performing information security and signals intelligence does not carry great meaning for most citizens. Because the business of making and breaking secret codes involves arcane mathematical theories totally removed from most folks' daily experiences, the press was content to let NSA remain secret until 1960, when two gay NSA analysts defected to the Soviet Union with shocking reports about the real business of the agency.

While the NSA was responsible for setting most of the directions for the U.S. computer industry in the 1950s, in order to have platforms optimized for code-breaking, the primary expenditures of the agency never have involved information security. Instead, NSA spent most of the 1950s on a global mission to expand U.S. bases, following in the footsteps of representatives of the Atomic Energy Commission and Strategic Air Command.

In the same way that many nations became hosts for nuclear weapons bases without the knowledge of the local population, some of these same nations established several U.S. bases dedicated to top-secret intelligence missions. Nations on the periphery of the Soviet Union, such as Turkey, Greece, Norway, and Pakistan, were hosts to several classified antenna and radar sites.

In most cases, local parliaments and congresses had no input into the treaties establishing these bases, which were drawn up among representatives of NSA, the White House, and sympathetic presidents or prime ministers in the host nations. To this day, members of parliaments, even in industrial U.S. allies like Great Britain, usually have no right to set foot inside the bases or ask questions of the executive branch regarding their purposes.

Nearby residents of large bases would give nicknames to the more obvious facilities. The huge Circularly Disposed Antenna Arrays, known by the U.S. military as "Flare-9" systems, were dubbed "elephant cages" by neighbors, due to the vast circular area enclosed by the antennas. Early sites with multiple radomes, such as Edzell in Scotland and Menwith Hill in Great Britain, became known as "God's golf ball" sites.

NSA's goal in establishing the global network was nothing less than the maintenance of a 24-hour, worldwide intelligence system capable of intercepting any communication of interest to the U.S. government. When the United States and Soviet Union relied on a mutually-assured-destruction nuclear weapons policy, such a network might have been seen as necessary. But from its early days, the NSA interpreted its mission to include regular interception of domestic communications in the U.S., under programs with code-names such as Shamrock and Gamma. During Congressional probes of the intelligence community in 1975, the NSA promised not to intercept domestic traffic, but the promises contained loopholes big enough to make the pledges all but meaningless.

Sulzman of CPIS warns that too many civil liberties advocates in the U.S. make a distinction between domestic and foreign interception that is inherently unfair. He suggests that "while it's OK to look at what NSA is doing at home, should we automatically assume that any interception network is automatically acceptable to set up merely because it's in a foreign nation?"

For many years, NSA was the budgetary favorite in the allocation by Congress of classified budgets for the intelligence community, and its annual expenditures still tally roughly $3.7 billion a year. But the establishment of the NRO in 1960 set the stage for the new space-intelligence agency becoming the most profligate spender on the block.

NRO began as a virtual paper agency to coordinate the space missions of CIA, NSA, and the Air Force's Space and Missile Systems Organization. Even today, NRO is more of a budget manager than a true agency with thousands of people in the field. Yet it spends $6.2 billion a year on classes of satellites U.S. citizens know nothing about.

From the time President Kennedy classified all information about U.S. spy satellite missions in the early 1960s, analysts have had to make educated guesses about the evolution of photographic and radar imaging satellites. Early systems used film canisters that were ejected from satellites as they re-entered the atmosphere. The canisters had to be snagged by special planes outfitted with large nets behind them, a demanding and exacting task conducted outside any public knowledge.

Later photographic satellites turned to real-time electronic imaging of the planet, sending their information down to ground bases. As new photographic satellites like Big Bird and Keyhole were deployed, new bases such as Pine Gap in Australia were established to serve as the downlink for such satellites.

Imaging satellites played a much greater role in disproving the so-called "missile gap" with the Soviet Union, and in documenting the transfer of intermediate-range missiles to Cuba in October 1962, than was acknowledged at the time. They continued to play a primary role in crises in Vietnam and the Middle East during the 1960s. Yet the NRO acronym was never mentioned in public. The existence of the agency only began to be rumored in the mid-1980s, and its existence was not declassified until 1993.

In recent years, the NRO has gone public with a series of workshops and documents describing the early years of the imaging satellite program. In general, imaging and infrared satellites are perceived as the most defensible and stabilizing systems run by NRO, since their primary purpose is to map overt physical acts, thus providing a basis for treaty verification.

But beginning in the early 1970s, the core missions of the NRO began to turn away from imaging, and toward serving the NSA with space-based communications intelligence, something much harder to doctrinally justify as defensive. One strategy in moving many signals intelligence resources to space was to avoid turmoil in land-based facilities. It is no accident that this trend arose as developing-nation liberation movements were in their heyday. The NSA had to cope with revolts at bases in Thailand and Vietnam in the waning years of the Vietnam War. And prior to the main hostage crisis in Iran in 1979, a smaller hostage crisis had arisen in February 1979 over NSA agents held prisoner at bases in Kabkan and Klarabad, Iran.

High-tech advocates in the Ford and Carter administrations promoted the shift of signals intelligence resources to space. The program began with low-orbit satellites with short lifetimes, under the Jumpseat and Farrah/Raquel programs of the 1970s. Some listening satellites were launched as "piggybacks" to photographic spy satellites, while some were given launch vehicles of their own.

The success of early experiments convinced the Air Force and NSA that a good deal of communications intelligence could be moved to space. Plans for multibillion-dollar geosynchronous satellites (residing at 24,000-mile orbits where they "hover" over one location in synchrony with earth's orbit) were set in motion, with funds for the satellites hidden as part of Reagan's budget-busting arms buildup. Originally, these satellites were supposed to be the primary user of a special launcher to be carried in the bay of the space shuttle, a system called the Inertial Upper Stage. Under the original plans of having the shuttle serve as the key national-security platform launcher, Falcon Air Force Base east of Colorado Springs was to serve as the Consolidated Space Operations Center, the core downlink for classified programs of the shuttle.

The Challenger disaster of 1986 changed those plans. Scaling back Falcon's mission sent the Colorado Springs economy into a tailspin (and indirectly led to the proliferation of evangelical Christian organizations in the city, since the city-financed El Pomar Foundation used the excuse of the Falcon cutbacks to launch a campaign to recruit evangelical groups to "diversify" the economy). Losses for Colorado Springs meant gains for Denver, since the Air Force decided to switch large national-security payloads to the Titan-IV rocket, built by Martin Marietta in southwest Denver. It is important to recognize that the Titan-IV, this nation's largest launch vehicle, has been used solely for the purpose of classified payloads, and that the upcoming contested launch of the Cassini space probe in October 1997 will be the first time Titan-IV will have been used for an acknowledged mission.

The shift in intelligence platforms initiated during the Reagan years provided the technical intelligence community with a useful sleight of hand when the socialist world crumbled in the late 1980s. Soviet signals intelligence agencies, including the GRU and a special branch of KGB, had been overextended even prior to the fall of the Berlin Wall. Between late 1989 and the hard-line coup of August 1991, many Soviet listening posts in locations such as Cam Ranh Bay, Vietnam, and Socotra, Yemen were scaled back or closed. (The oft-cited Russian signals base in Lourdes, Cuba remains one of the few foreign signals bases still maintained in good condition by the current strapped Russian government.)

The U.S. military made a show of consolidating or phasing out certain bases in Turkey, Crete, and Germany, but most of the "drawdown" was simply a public relations gambit. In some cases, bases were shifted from one nation to the other -- when the U.S. was kicked out of Iran, for example, China allowed two new U.S. signals bases to be constructed at Qitai and Korla in Xinjiang province, while Pakistan allowed the reopening of a base dating from the 1950s. In other nations, elephant cages were closed, while satellite downlink bases were expanded to prepare for the expansion of signals intelligence satellites. Germany provided a textbook case for this trend, as the satellite base at Bad Aibling expanded even as the staff at the elephant cage at Gablingen shrunk.

A critical factor to emphasize is that the Gulf War halted any talk of a "peace dividend," particularly within the intelligence community. Longstanding congressional and executive pledges of providing the NSA and NRO with everything the agencies asked for, continued unabated in both Bush and Clinton administrations. Former CIA Director James Woolsey set the stage with his message to Congress that the dragon (Soviet Union) may have been slain, but that there were "plenty of snakes in the jungle", requiring the maintenance of a permanent global intelligence infrastructure.

When pressed, the U.S. intelligence agencies will admit to the bare-bones details of photographic imaging or infrared monitoring satellites, since these satellites have a more stabilizing justification in monitoring situations like the Iraqi and North Korean arms buildups. But NRO signals intelligence missions carried out for NSA's benefit remain the most highly secret aspect of the U.S. intelligence mission, even though they constitute the bulk of the current $28 billion annual expenditures of the intelligence community. (Simple addition of NSA's $3.7 billion annual budget and NRO's $6.2 billion budget would yield a $10 billion total. However, much of the money for space SIGINT support is hidden away in small intelligence agencies, such as the Air Force's Air Intelligence Agency, and in special inter-agency projects. TIARA [Tactical Intelligence and Related Activities], for example, consumes more than $10 billion of the total, and is used for funding "tactical" programs like the Talon missions at Falcon AFB.)

In the Clinton administration, we have entered a new era, in which multibillion-dollar satellites lofted into orbit by the Titan-IV provide unprecedented opportunity to intercept communications in a wide range of frequencies, never before attempted from space. These new classes of satellites, bearing names such as Advanced Jumpseat, Advanced Vortex, and Advanced Orion (the latter sometimes called Trumpet or Jeroboam), have been launched in the last four years with virtually no coverage from the national media. Colorado residents often get an indirect idea that a launch has occurred, when Lockheed-Martin takes out full-page ads in the daily papers to congratulate its employees on another successful Titan-IV launch -- even though no details of payloads are ever released.

While the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization bragged for several years about the move to smaller and less expensive satellites (the Star Wars programs called Brilliant Pebbles and Brilliant Eyes were based on such concepts), such thinking never registered with NRO. This might seem odd, since the Star Wars Clementine program to explore the moon was cited by NASA as a fine example of how to accomplish space missions cheaply.

Yet NRO did not establish a small satellite office until early 1996. And when it presented its five-year program to Congress in the fall of 1995, the new satellites under development -- including a photographic satellite called 8X and a signals intelligence satellite called Intruder -- were almost all billion-dollar monsters. The rationale for failing to "think small" was unclear until Robert Dreyfuss published the article `Orbit of Influence - Spy Finance and the Black Budget,' in the March-April 1996 American Prospect magazine. In it, Dreyfuss described the lobbying work Lockheed-Martin chairman Norm Augustine performed with Newt Gingrich in 1995, to insure that the NRO did not turn to small satellites. In effect, the gargantuan satellite program has become one of the military's most overt cases of corporate welfare -- the 30,000-pound satellites exist to protect jobs at Waterton Canyon and other facilities, not because they serve national interests.

In one very ugly sense, however, the big birds do indeed serve national interests -- because the national interests for space have become nakedly belligerent in the aftermath of the Gulf War. Beginning in the early 1990s, the public statements of officials of the U.S. Space Command at Peterson and Falcon Air Force Bases became notably more bellicose, promoting the concept of space domination by the U.S. as a god-given right. Falcon began touting its "Masters of Space" logo proudly, and Space Command officials like Gen. Charles Horner started suggesting that, not only could the U.S. justify maintaining 24-hour space-based reconnaissance of the planet, but it should be the only nation allowed to maintain such capabilities.

This doctrine fit with the opening of the Space Warfare Center at Falcon in late 1993. Local media representatives were perplexed, because the new center was established at a time the U.S. was supposedly phasing out Star Wars. What most analysts failed to perceive was that, as missile defense shifted from the Strategic Defense Initiative Organization to the smaller and land-based Ballistic Missile Defense Organization, the U.S. Space Command shifted its main mission from Star Wars to support of the NRO. And the spying mission was not just to fill the data storage facilities at NSA headquarters at Fort Meade and NRO headquarters in Chantilly, Va. It was meant to give any tactical commander in the field complete intelligence of an adversary's resources.

In 1994, Falcon began a highly-classified series of missions called the Talon series, involving experiments in "fusing" the intelligence collected by satellites with mapping information, photographic intelligence, and communication intelligence from ground stations. In 1996, a new Talon mission called Talon Knight even extended the program to include individual ground-based agents of the Special Forces. An accurate three-dimensional image of a particular area, with radar and communication sources identified, could then be sent to anyone in the field, such as a tank commander or fighter pilot.

The goal was to make sure every battle could be turned to a "turkey shoot," similar to the slaughter of Iraqis on the road to Basra during the Gulf War. Since the American public often demanded kill ratios of thousands-to-zero for any conflict involving U.S. troops, military leaders anticipated that any capabilities allowing potentially no casualties for the "good guys" would be immensely popular with the public. So they started bragging about it.

Jeffrey Harris, the NRO director who was ousted for fiscal improprieties in February 1996, gave one of NRO's first public speeches in Colorado Springs in April 1995, and boasted to the Space Symposium '95 audience that "we're moving terabyte-miles per second through intelligence networks in order to provide real-time intelligence to the warfighter." His comment proved so popular, that Northrop-Grumman turned "real-time intelligence to the warfighter" into a corporate slogan at the next year's Space Symposium.

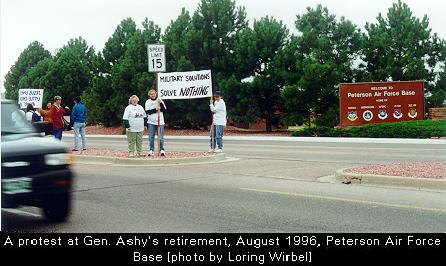

Year by year, the Space Command has gotten more up-front about using intelligence as a "force multiplier," about seeking an end to the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty to allow for any use of missile defense, and about blithely ignoring the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which supposedly bars the use of space as a platform for war preparation. In early August 1996, outgoing head of the Space Command, Gen. Joseph Ashy, told Aviation Week & Space Technology, "It's politically sensitive .... and it isn't in vogue, but - absolutely, we're going to fight in space. We're going to fight from space and we're going to fight into space." And the proactive use of intelligence to allow for pre-emptive missions is a key part of that doctrine, Ashy emphasized.

"In a sense, the heads of NRO and Space Command are our best public relations resource," Sulzman said. "They're up front about their goals, because they feel like they don't have to care."

Even some U.S. citizens who support a total battlefield dominance scenario enabled by NSA and NRO might not support the agencies' expanded missions in the field of commercial and civilian intelligence. In efforts predating the decline of the Soviet Union, members of the executive branch have prodded the technical intelligence agencies to move back into civilian monitoring -- first to monitor money-laundering, then to track drug networks, and most recently to provide U.S. transnational corporations with commercial advantages in conducting business globally. The main focus of the U.S. flap with France over intelligence abuse in February 1995, for example, was over provision of NSA and NRO information to Raytheon and other U.S. companies, allowing them to win out over French competitors in foreign contracts (though the U.S. could rightly claim that French intelligence had been doing the same thing for years).

As part of its philosophy of supporting "free trade" while creating unfair advantages for U.S.-based firms, the Clinton Administration has strongly supported this misuse of technical intelligence.

But does this abuse in commercial realms spill over into analysis of individual citizens? Circumstantial evidence would strongly suggest it does. NRO, unlike NSA, never made any promises in 1975 to avoid domestic surveillance, because most members of Congress were unaware of its existence at the time. And NSA has regularly provided "broadband intercept" information to the FBI and other agencies to help them identify the targets for wiretaps that are brought before the nation's secret "star chambers" court for wiretapping, the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act court.

The real breakout for NSA and NRO in domestic surveillance occurred with the passage of the Digital Telephony Act of 1994 and the Telecom Reform Act of 1996. The former act required that telephone companies make their digital networks capable of being tapped, and that the price of such technology be borne by taxpayers and by the phone companies' customers. While FBI Director Louis Freeh was believed to be the major proponent behind the Digital Telephony Act, its real sponsors were the NSA and NRO, according to several Washington insiders.

In early 1995, NSA and the Naval Research Labs encouraged all the major Regional Bell Operating Companies to join Project MONET (Multi-wavelength Optical Network), supposedly a coalition effort to teach telephone companies how to install optical fiber backbones for Internet traffic. But an AT&T press release issued at the time MONET was announced said that the primary purpose of the coalition was to meet "defense and security needs of the nation."

These same phone companies have been taking over the Internet switching centers originally run by the National Science Foundation, known as Network Access Points or NAPs. NAP developers freely admit that, contrary to popular belief, optical networks can be tapped through new optical packet-copying test equipment. And a source at one large optical test equipment vendor said that large orders for such equipment have been coming from Fort Meade, Maryland in recent months -- intended for delivery to the NAPs.

Does this mean all our Internet traffic is regularly monitored? There is not enough equipment, and nowhere near enough human analysts, to make such a surveillance network a reality. But in an atmosphere in which the so-called liberal president, Bill Clinton, calls for "more wire taps, many more wire taps" in his re-nomination speech to the Democratic Convention, we can be sure that all the capabilities for selective surveillance are being put in place, and few Washingtonians in positions of power are making any complaints.

In the last three years, the technical intelligence agencies' chutzpah in ignoring the democratic process has landed NSA and NRO in hot water, though widespread public knowledge of most scandals is still minimal.

The NSA has a 20-year history of trying to ban private research into secret-code theory, in order to prevent computer encryption methods the agency cannot control. The popularity of a grassroots coding method called "public-key encryption" in the last few years has alarmed the NSA, forcing the agency into taking a lead role in trying to force the use of an NSA coding program called Clipper. The heavy-handed methods employed by NSA sparked an anti-agency movement on the Internet, in which "cyber-libertarians" pledged to do everything possible to foil NSA plans.

This movement has a hint of macho unreality to it, as independent cryptographers have a naive belief that it would be easy to foil the NSA. But the movement has been useful in disrupting a tacit agreement in the past between the agency and its crypto-critics. In the 1970s and 1980s, mathematicians often criticized the computer-security missions of the NSA, while being careful not to critique the NSA's global signals intelligence network.

In recent months, the White House has tried to scare NSA critics by offering them a classified "briefing" explaining why Clipper coding programs are necessary. The efforts have angered independent cryptographers like Whitfield Diffie of Sun Microsystems, who say that it is time to raise the question of the legal base for NSA running a global reconnaissance network. It appears that many crypto-critics are ready to take on the legality of the NSA's signals intelligence mission.

Meanwhile, NRO has been battered at every turn for its free-spending, unaccountable ways. In late 1993, Congress issued a classified denunciation of NRO for ignoring a Congressional order to halt funding on a system called Wide Area Surveillance System. Apparently, NRO officials blithely ignored Congressional directives and let contracts for the system without approval.

The hand-slap was only the beginning of NRO's problems. In the summer of 1994, the agency took intense heat for planning a $350 million headquarters building in Chantilly, Va., supposedly without approval of Congress. Hearings that summer showed that Congress regularly approves NRO budgets without understanding what programs or construction projects representatives are voting on.

The Chantilly dispute involved pocket change, however, compared to problems revealed at the end of 1995. NRO admitted in November to not being able to account for more than $1 billion out of its $6 billion Fiscal Year 1995 budget. During the course of the next few months, the news got worse and worse. The amount escalated to $2.5 billion by February, when CIA Director John Deutch fired NRO Director Jeffrey Harris and Deputy Director Jimmie Hall. At last count, the NRO inspector general estimated that more than $4.5 billion in the NRO budget cannot be accounted for, due to excess secrecy in the agency's programs.

Although the technical intelligence community has had its dirty laundry washed in public for many months, it has been hard to translate the scandals into political scrutiny. Many Democrats, including defense critics serving on the Intelligence Committee like Rep. David Skaggs, accept most of the goals of NSA and NRO. In fact, the toughest criticisms have come from Republican budget hawks like John Kasich, rather than Democrats.

The shift of NSA and NRO from stabilization to provocation, however, is not new. In his 1980 book on signals intelligence bases in Australia (A Suitable Piece of Real Estate), arms researcher Desmond Ball suggested that there were similarities between missile accuracy and intelligence accuracy. Many nuclear arms analysts accept the theory that, as a missile warhead becomes more accurate, a nuclear-war doctrine automatically becomes a first-strike silo-busting doctrine, regardless of the announced intentions of those deploying the missiles.

Similarly, Ball suggests, if intelligence capabilities become global and operate in near-real-time, they encourage provocative military actions. Ball wrote that "The removal of uncertainties surrounding the strategic capabilities of an adversary is not always a good thing. Surveillance technology need not and should not have been developed to the point where strategic forces can be located to within one or a few feet of their exact positions."

This comment was made in an era when a true strategic adversary to the U.S. existed. Unfortunately, U.S. strategists not only overtly aimed at pinpoint intelligence, they preserved this strategy after the other superpower self-destructed. And they bragged about the pre-emptive, provocative purposes to which this intelligence is applied against much smaller, developing-nation adversaries. At the same time, the agencies overtly look for new targets such as drug-dealers, money-launderers, and even civilian political enemies in order to justify continued high expenditures.

President Clinton's support of a vastly expanded national security state illustrates the problems in trying to make the new intelligence structure and targets an issue for activists. Too many progressives have made compromises with government programs that leave them tacitly supporting the government, as many in the right-wing militia movement have learned.

The anti-NSA positions of cyber-libertarians on the Internet often sound more like the anti-government ramblings of the right than the intelligence critiques developed by left critics during the 1970s. Consequently, all too many arms control activists have ended up tacitly supporting the technical intelligence agencies because of their roles in monitoring arms treaties. Anti-Star Wars crusader Robert Bowman has gone so far as to suggest most NSA and NRO financing is inherently stabilizing.

There are many world citizens, from activists in Turkey and Greece to anti-base protesters in Japan and Thailand, who would argue strongly against that position. NSA, in particular, has regularly provided tacit support for coups that would protect the existence of bases on foreign soil. The agency encouraged the Turkish coup of 1980, was involved in several actions to support the Greek military in the 1960s and 1970s, and was a key player in the "constitutional coup" that removed Australian prime minister Gough Whitlam from power in November 1975.

The new moves by NSA and NRO to "serve the warfighter" would seem to be a natural area for peace organizations to get involved in opposing the agencies. But, as John Pike at Federation of American Scientists points out, most peace organizations are woefully lacking in knowledge on the intelligence community. And far too many such groups nationwide are virtual shells, with money and people drained from the organizations since the START treaties were signed in the early 1990s.

In Colorado, activists have learned that allies and enemies cannot be presumed in advance. Democrats in general have turned into defenders of larger defense budgets. Members of the Congressional Black Caucus, for example, were critical for Fiscal 1996 budgets in supporting additional Seawolf submarines and B-2 bombers in order to protect manufacturing jobs in California. And similar trends exist for intelligence budgets.

Rep. Pat Schroeder, to her credit, provided some support for raising Buckley awareness before she left Congress. But her Democratic colleague David Skaggs, who sits on the Intelligence Committee, consistently has failed to take the lead in ending the intelligence abuses of the NSA and NRO. When he met with activists in December 1995 and was asked why conservative Republicans were the first to talk of reducing the NRO budget, Skaggs defended the vast bulk of NSA and NRO missions as necessary. And too many activists in Skaggs' home district of Boulder and surrounding environs are reticent about rocking the boat, limiting the ability to challenge his position.

By contrast, some Republicans in the "budget-hawk" wing of the party have been loud and constant critics of the NSA and NRO. And awareness of the agencies' roles in Colorado has come from surprising sources. For example, the Denver Business Journal in its special April 1995 issue on `Colorado's Stealth Economy' issued a strong editorial warning against unbridled intelligence spending. The business community thus has realized the problems of NSA and NRO expansion before many in the Colorado religious and lay peace communities have caught on -- something that Colorado Springs activists have had to reiterate again and again.

Colorado activists have a long history in taking bold actions against militaristic space programs. "Marie Antoinette" was arrested in a theater action in the late 1980s, and a bison was released on Falcon Air Force Base property in 1991. But one key to making an effective challenge to NSA and NRO expansion was the formation in 1992 of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space.

At its inaugural Washington, D.C. meeting in 1992, the group was focused on documenting the shift to land-based missile-defense weapons, and on opposing deep-space plutonium-powered missions, similar to the Galileo mission which had been strongly opposed by the Florida Coalition for Peace and Justice.

But at national meetings in Colorado Springs in 1993 and Albuquerque in 1994, the group began exploring the intersection between technical intelligence agency expansion and the new bellicosity of the U.S. Space Command. National organizers like Bruce Gagnon of the Florida Coalition and Connie Van Praet of the Institute for Security and Cooperation in Outer Space, helped ground the local concerns of Buckley activists in a national perspective.

The March 1993 meeting of the Global Network created the groundswell for the first two demonstrations outside Buckley -- a small initial gathering on June 3 of that year, and a larger multi-organizational protest on Sept. 11. The latter event was noteworthy for bringing in speakers from organizations as diverse as American Indian Movement and Sisters of Loretto. Yet the blackout by area news media was virtually complete.

Activists learned the hard way during mid-1993 that news outlets simply did not want to lift the veil of secrecy at Buckley -- whether the outlet was a local television station, the Denver Post, or the "alternative" weekly Westword. Rep. Schroeder's office supplied an interesting line item from the Fiscal 1994 Military Construction budget, showing that a $39 million computer expansion project at Buckley carried the priority designation "FAD DX Brickbat" -- a strategic classification which Federation of American Scientists claims is normally reserved only for nuclear weapons projects. Yet media representatives brushed off the demonstrations and press conferences as uninteresting.

Because music, dance, and theatre have played such a critical role in recent Colorado protests, it was hard to tag the June and September demonstrations with adjectives like "uninteresting." Boulder drum and dance artist Lindy Lymon developed a special "see no evil" presentation for the September action. First Strike Theatre, Colorado Springs' award-winning progressive theatre group, presented a "Re-Press Conference" in September to poke fun at the media's shunning of the Buckley subjects.

First Strike members Mary Sprunger-Froese, Lyn Boudreau, and Buck Buchanan penned several songs on Buckley secrecy, including "We Don't Talk About That." First Strike also supported a continued Buckley interest in the general community by using several references in its "Star Whores" theatre program, and by making a Buckley slide show a primary focus of its 1995 "War's Own - Piece de Resistance" performance.

Despite being ignored by mainstream powers, Colorado groups made special efforts to reach out to other community organizations in Denver, Boulder, and Colorado Springs in late 1993. This groundwork sent Citizens for Peace in Space to Albuquerque in good spirits for the January 1994 meeting of the Global Network. Keynote speaker Michio Kaku later decided to make NSA and NRO trends a feature of his weekly radio show on WBAI in New York. A feature in The Progressive magazine also gave CPIS some national awareness.

But 1994 proved a year of disappointment and retrenchment. Several new geosynchronous satellite systems had their maiden launches on Titan-IV rockets in 1994, with no coverage from the media. President Clinton, under fire from conservatives destined to take Congress, made clear that he supported larger defense and intelligence budgets. The NSA and NRO announced the creation of several global joint bases, called Regional SIGINT (Signals Intelligence) Operations Centers, or RSOCs. In addition to Buckley, domestic RSOCs were planned for Medina Annex in San Antonio and Fort Gordon in Georgia, yet it was difficult to spur local organizers in those areas.

In a series of meetings in late 1994 and early 1995, Colorado groups decided to turn up the heat on Space Command facilities. A series of actions, both legal demonstrations and direct-action civil disobedience, were planned for 1995. The activists set 1996 as the year to take on Space Command headquarters at Peterson directly.

CPIS public information forums try to draw a balance between factual presentations and discussions of moral issues. Mary Lynn Sheetz, a graphic designer and long-time community activists involved in several direct actions, likes to bring in the uninitiated by making the analogy of a weapon.

"One need not be aware of the caliber and firepower of a pistol to understand that it is wrong to point that pistol at a child," she has said at several workshops.

A still-unfulfilled goal of the groups is to aim more attention at defense contractors, particularly Lockheed-Martin. Since Lockheed took over the Martin-Marietta spy satellite facility in Waterton Canyon south of Denver, and since the merged company acquired Loral Federal Systems and Loral's important intelligence operations in Colorado Springs, the company has become the undisputed leader in black-budget support operations. Yet the levels of security at Waterton have discouraged protests at that facility to date.

Legal demonstrations in 1995 at Buckley, held on May 20, June 5, and July 3, generated the usual low levels of interest in Denver. But a June 19 civil disobedience action represented a breakthrough. Air Force Military Police elected to take a surprisingly hard line when six protesters tried to walk into the cordoned-off Aerospace Data Facility area. Two protesters were tackled to the ground, water cannons were trained on the group, and a photographer from the Rocky Mountain News had his film confiscated. This rash action helped the activists' cause, as it was one of the factors that convinced Rocky Mountain News editors to publish an expose of Buckley Field that ran in an October Sunday edition.

Activists tried hard to draw links between Colorado facilities. On July 16, 1995, the 50th anniversary of Trinity, demonstrators bannered Falcon Air Force Base to alert the public that one of the secret Talon experiments was going "live."

Project Strike, initiated at Falcon on July 19, fed information from spy satellites and NSA ground stations directly into the cockpits of B-1B and F-15E planes flying from Ellsworth AFB, South Dakota.

Space Command reaction was inconsistent, to say the least. When activists again tried to enter Buckley in October, they were gently expelled from the base perimeters several times, no doubt in an effort by base officials to avoid the negative publicity generated in June. But when six activists entered Peterson on Feb. 12, 1996, to deliver an inquiry letter to Space Command head Gen. Joseph Ashy, the Space Command asked the city of Colorado Springs to act against the protesters, and encouraged a hard line during prosecution.

Media reaction was just as inconsistent. The Rocky Mountain News and Denver Business Journal belatedly recognized the profound role Buckley plays locally. Interest on the Internet is high, as well. However, TV media in all major Colorado markets, and other daily newspapers throughout the state, including the powerful Denver Post, could not be more disinterested.

Even as Colorado groups recognized the importance of carrying out continued local actions, they also made new efforts to link up with international movements. Since early 1993, a women's peace camp at the Menwith Hill NSA station in England has raised the bar for overt actions at bases. Women have maintained a constant series of blockades and "invasions" at the base, which has expanded tremendously in the 1980s and 1990s, carrying out such new missions as the STEEPLEBUSH series of missions to spy on European civilians.

Because the status of Menwith Hill as a sovereign base is uncertain, women have been bold in their actions, going into radomes directly to grab classified documents, and to spray-paint radome surfaces with slogans such as "Stop the NSA War Criminals." In most cases, the women have been found innocent, or have received light sentences because magistrates are unconvinced that Menwith Hill is a legal facility under British law. The BBC carried a documentary on the women of Menwith Hill in 1994, narrated by Duncan Campbell, the journalist who initially exposed Menwith Hill in 1979. Colorado groups have used this video as an organizing tool, and have remained in regular contact with the women's peace camp.

Important movements in the Pacific Rim also are challenging the NSA and NRO. Australian protesters have targeted the Pine Gap and Nurrungar intelligence bases for the last 15 years, and Okinawan protesters made the Sobe Communications Station "elephant cage" a particular target of their anti-bases ire in Japan.

The latter half of 1996 and early 1997 are anticipated to bear fruit in the campaign to internationalize the anti-bases efforts. In May, members of the Global Network met near Cape Canaveral, Florida, after a 16-month hiatus, to revitalize space peace campaigns. Colorado activists prepared a list of intelligence support facilities in Florida to indicate to locals the spread of NSA's and NRO's reach.

John Pike of Federation of American Scientists indicated the ways the Internet can be used to increase information on intelligence bases. The FAS Web site is a source for much emerging information on intelligence base facilities. Pike and Steve Aftergood of FAS also have initiated a "Check it out!" campaign on Usenet newsgroups, in which newsgroup subscribers swap information about mysterious facilities in local neighborhoods.

"This not only helps us understand where employees of the intelligence agencies go to work every day, but also makes it very real for people about where all those billions of dollar go every year," Pike said. "We're in pretty good shape for the Washington area and for Colorado, but where are our amateur agents in the Los Angeles area? Where is the work in San Antonio? We need to make this a broader effort."

In February 1997, the Global Network hopes to broaden its efforts further with an international meeting in Germany. In addition to making it more likely to bring in a Menwith Hill contingent, Global Network organizers looked to Germany because of the location of Bad Aibling, a satellite base that appears to be Buckley's sister facility for Europe. Activists also hope to bring in representatives from Australia, where Pine Gap and Nurrungar are slated to expand under a revitalized U.S.-Australian treaty signed in July 1996; and from Okinawa, where activists are outraged over a Japanese Supreme Court ruling in August 1996 that allows the U.S. government to do what it wishes at its Okinawa bases.

The anti-bases effort continues to be an uphill struggle. Because the American economy remains so much stronger than any other regional economy, many U.S. allies not only expect, but demand, U.S. hegemony over military policies. Since many rebellious actions take place from an arch-conservative right wing, both in the U.S. and abroad, many liberals support a stronger national security state. And U.S. citizens enjoy the concept of a "Masters of Space" doctrine which would guarantee the U.S. military absolute control of a battlefield.

Nevertheless, members of the Colorado groups remain both hopeful of initiating discussion and change, and convinced of the necessity of working for such change. Sulzman said that "a multibillion-dollar budget which citizens cannot question or find out details about is simply irreconcilable with a democratic society."

One admittedly difficult, but unavoidable, subject that has slowed the Global Network's ability to build coalitions is the network's insistence on the hazards of using plutonium-based radioisotope thermal generators (RTGs) to build space probes. After the Challenger disaster, plutonium opponents like Bruce Gagnon of the Florida Coalition for Peace and Justice, and New York physicist Michio Kaku, were sure that the arms-control and anti-nuclear community would be united in their opposition to the use of RTGs carrying several tens of pounds of plutonium-238.

The Florida groups conducted a vigorous but ultimatelty unsuccessful campaign in the late 1980s against the Galileo space probe, aided by speeches from Kaku and articles from journalism professor Karl Grossman. The work in opposition to Galileo was crucial in forming the Global Network in 1992.

Yet several important groups have refuted the Global Network's former opposition to Galileo, and its present opposition to Cassini, a probe slated to be launched in October 1997. The Federation of American Scientists, which has been of immense help in aiding intelligence-reform projects, is reticent about formal work with Global Network, because FAS founders Carl Sagan and Jeremy Stone believe nuclear-powered probes may be necessary to explore the outer planets.

This did not hinder FAS' unofficial participation in the May conference, even though the focus of the conference was anti-Cassini organizing. The highlight of the Memorial-weekend conference was a May 26 demonstration at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station, where several groups united to call for an end to Cassini planning.

Colorado activists pointed out that Cassini will represent the first so-called commercial use of the Titan-IV, a rocket used only for national security launches up to the time of the planned Sept. 1997 launch. Gagnon and Kaku firmly believe that plutonium is used in NASA missions to prepare the American public psychologically for larger nuclearization of space. The Colorado groups have begun using the slogan, "If we consider the MX a weapon of war, if we consider the THAAD missile a weapon of war, we must consider the Titan-IV a weapon of war."

Some proponents of deep-space exploration think that Kaku, Grossman, and others may focus on too many unlikely scenarios when discussing the possibility of an explosion of Cassini during its launch, or during the "slingshot" maneuver in earth orbit which carries the probe to the outer planets. In the first place, launch accidents should not seem unlikely, after we have seen both Challenger and an early Titan-IV, carrying Navy intelligence satellites in 1993, involved in catastrophic explosions. Any repeat of this type of explosion with Cassini could lead to widespread plutonium dispersal.

But a larger issue was raised in a recent front-page article in the Santa Fe New Mexican. A July 29, 1996 study of accidents at Los Alamos National Labs shows a 22 percent increase in radiological accidents in the period of 1993 to 1995. The bulk of those accidents can be attributed to work on the Cassini space probe. A Cassini launch not only carries the potential of harming thousands of citizens -- it is already harming real people in its pre-launch phase.

-30-

| (Source - Jonathan's Space Report (Jonathan McDowell) No. 267 1995 Dec 8 Cambridge, MA; AP reports) | |||||

| Serial | Date | Model | Pad | Upper stage and payload | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Titan 4 launches from Cape Canaveral | |||||

| K-1 | 1989 Jun 14 | 402 | 41 | IUS/ USAF Defense Support Program (DSP) 14 early warning infrared system | |

| K-4 | 1990 Jun 8 | 405 | 41 | Navy Advanced PARCAE | (1) |

| K-6 | 1990 Nov 12 | 402 | 41 | IUS/ USAF DSP 15 early warning | |

| K-10 | 1994 Feb 7 | 401 | 40 | Centaur TC-12/Milstar 1 comsat | |

| K-7 | 1994 May 3 | 401 | 41 | Centaur TC-10/NRO Advanced JUMPSEAT | (1) |

| K-9 | 1994 Aug 27 | 401 | 41 | Centaur TC-11/NRO Advanced VORTEX | (1) |

| K-14 | 1994 Dec 22 | 402 | 40 | IUS/ USAF DSP 17 early warning | |

| K-23 | 1995 May 14 | 401 | 40 | Centaur TC-17/NRO Advanced ORION | (1) |

| K-19 | 1995 Jul 10 | 401 | 41 | Centaur TC-8/NRO Advanced JUMPSEAT | (1) |

| K-21 | 1995 Nov 6 | 401 | 40 | Centaur TC-13/Milstar 2 comsat | |

| ? | 1996 April 24 | Centaur/Advanced VORTEX | |||

Titan 4 launches from Vandenberg AFB: | |||||

| K-5 | 1991 Mar 8 | 403 | 4E | NRO LACROSSE 2 | (1) |

| K-8 | 1991 Nov 7 | 403 | 4E | Navy Advanced PARCAE | (1) |

| K-3 | 1992 Nov 28 | 404 | 4E | TPA/Improved CRYSTAL 2 | (1,2) |

| K-11 | 1993 Aug 2 | 403 | 4E | Navy Advanced PARCAE | (1,3) |

| K-15 | 1995 Dec 5 | 404 | 4E | TPA/Improved CRYSTAL 3 | (1) |

| ? | 1996 May 12 | Navy Wide Area Surveillance System | |||

Notes: | |||||

| (1) Classified payload, true name unknown. 'Advanced X' indicates a new generation replacing the series which had codename X. PARCAE was a US Navy intelligence spacecraft. JUMPSEAT and VORTEX were USAF/NSA electronic and signals intelligence payloads. ORION was a CIA signals intelligence spacecraft. LACROSSE is a radar imaging satellite. Improved CRYSTAL is an optical and near infrared imaging satellite. All of these missions are classified and my analysis is based on guesses from information in the open literature. | |||||

| (2) Titan model 404 may possibly carry the Titan Payload Adapter (TPA) designed to support payloads originally built for Shuttle launch. | |||||

| (3) Launch failure | |||||

Resources

Ball, Desmond, A Suitable Piece of Real Estate. Sydney: Allen & Unwyn, 1980.

Bamford James. The Puzzle Palace. NY: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1983. (A new edition is scheduled for early 1997 release, in which co-author Wayne Madsen adds several critical features on NSA's use of the Internet.)

Bunn Dina. "Schroeder Protests Guards' Acts at Buckley." Rocky Mountain News, p. 14A, June 20, 1995.

_______. "The Secret of Buckley Field." Rocky Mountain News, p. 1, Oct. 15, 1995.

_______. "4 Protesters Fail to Enter Buckley Base." Rocky Mountain News, p. 5A, Oct. 24, 1995.

_______. "More Golf Balls at Buckley Bring Expansion to the Fore." Rocky Mountain News, p. 18A, Jan. 15, 1996.

Campbell, Duncan. The Unsinkable Aircraft Carrier. London: Michael Joseph Ltd., 1984.

Hager, Nicky. Secret Power. Nelson, New Zealand: Craig Potton Publishing, 1996.

Olgiersen, Ian, Aldo Svaldi, et. al. "Colorado's Stealth Economy." Denver Business Journal (special issue), April 11-15, 1996.

Pike, John. "Spies in the Skies: The National Reconnaissance Office and the Intelligence Budget." Covert Action Quarterly, Fall 1994, p. 48.

Richelson, Jeffrey and Desmond Ball. The Ties That Bind. Cambridge, Mass: Allen & Unwyn/Unwyn-Hyman Inc., 1990.

Richelson, Jeffrey. The U.S. Intelligence Community. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press, 1995.

Wirbel, Loring. "Undisguised Spies." The Progressive, Aug. 1993, p. 15.

On the Internet: John Pike of the Federation of American Scientists manages a wonderful and informative home page for the FAS's Intelligence Reform Project. The FAS general Web site and introductory home page is at the URL http://www.fas.org, while the IRP's home page is at http://www.fas.org/irp/. (Compare this with the National Reconnaissance Office's paltry home page, at URL http://www.nro.odci.gov/.) For updates in Usenet newsgroups, check alt.politics.org.nsa.

-30-

Loring Wirbel has studied signals intelligence networks for nearly 20 years, and has prepared reports on Colorado facilities for Citizens for Peace in Space and the Pikes Peak Justice & Peace Commission in Colorado Springs. He is communications editor for Electronic Engineering Times, and is working on a book about foreign bases and their role in signals intelligence strategies.