It was a grumpy Rob Muldoon who walked across from the Beehive building to the parliamentary chamber on Tuesday, 12 June 1984. After nine years as an increasingly embattled prime minister, his rule was disintegrating. That morning the Leader of the Opposition, David Lange, had announced his party's foreign policy: New Zealand would be made unconditionally nuclear free and the ANZUS Treaty would have to be renegotiated. Later that day two National Party MPs crossed the floor in Parliament to vote for a Labour Party-sponsored Nuclear Free New Zealand Bill, almost defeating the government. Two days later, blaming these anti-nuclear defectors, a visibly intoxicated Muldoon threw in the towel and called an early general election.

That Tuesday afternoon Muldoon was on his way to the 2.30 pm session of Parliament to read a prepared ministerial statement about a quite different subject: an obscure agency called the Government Communications Security Bureau (GCSB). The GCSB had been set up secretly under Muldoon seven years earlier and had been quietly growing in size throughout his reign.

Until just two months before Muldoon's statement the public had never even heard of the GCSB. Then peace researcher Owen Wilkes publicised the existence of a secret radio eavesdropping station run by the GCSB at Tangimoana Beach, 150 kilometres north of Wellington, revealing for the first time that New Zealand was involved in this type of intelligence collection. Muldoon was delivering the government's reply to the publicity.

The brief statement he read was, and remains, the most information the government has ever been prepared to release about the GCSB and the Tangimoana station. It acknowledged that the GCSB was involved in signals intelligence " intercepting the communications of governments, organisations and individuals in other countries " and said New Zealand had collected that type of intelligence since the Second World War. It noted that the GCSB liaised closely with Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States -- the closest the government has ever come to talking about the secret five-nation signals intelligence alliance of which the GCSB is part. But much of the statement was designed to mislead.

It said that the Tangimoana station did not monitor "New Zealand's friends in the South Pacific". The big aerials at the station were right then monitoring nuclear-free Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands, Fiji and all New Zealand's other South Pacific neighbours -- everyone in the South Pacific, in fact, except for the Western intelligence allies and their territories. Large quantities of telexes and Morse code messages sent by long-distance radio in the Pacific region were being recorded at Tangimoana and sent to the GCSB in Wellington for distribution to select public servants and to the four intelligence allies.

The statement also said that Tangimoana "does not come under the direction of any Government, or external agency, other than the New Zealand Government". In fact, the communications officers in a secure room within the station were regularly receiving directions from the overseas allies and sending them back intelligence collected on their behalf.

As soon as Muldoon sat down, the Leader of the Opposition stood up to respond. Lange, who five weeks later would be Prime Minister, thanked Muldoon for removing the cause of suspicion which had surrounded the Tangimoana facility: "In particular, I am grateful that he has given an absolutely unqualified assurance, which I believe to be of paramount importance, that the facility is under the full control of the New Zealand Government".

On that same Tuesday one of the GCSB's newest employees left for work from his home in Khandallah, overlooking Wellington Harbour. He had recently moved into a key position overseeing the GCSB's policy and planning. After the GCSB director, this would be the most influential position in determining the GCSB's direction through its most important period of growth.

Glen Singleton had already made an impression on his colleagues. He was always polite and sociable, but kept his opinions to himself. Privately, he told work friends that he did not much like the top people at the GCSB. The other directors at the GCSB, mostly ex-Air Force, had little in common with his tastes for antiques, paintings and good food.

Arriving at work, Singleton took the lift to the 14th floor of the Freyberg Building headquarters. He held his magnetic security pass up to the right spot on the heavy wooden doors and an unseen black box registered that he had arrived and automatically opened the door.

In 1984 this top floor contained the GCSB's communications centre, its 24-hour link to its overseas allies, the linguists who translated intercepted messages and some of the deputy directors. Singleton's office had been positioned next to the director's, with wide views across the harbour. Staff recall that "he wandered in and out of the director's office whenever he wanted" and that he "had the director's ear".

One of the many things Lange did not know about the GCSB when he spoke in Parliament that afternoon, and would never know, even as Prime Minister, was that this new officer was not under the control of the New Zealand government at all. Paid in American dollars and living in a house rented for him by the local United States embassy, Singleton was an employee of an organisation called the National Security Agency (NSA).

The NSA is the United States' largest, most secret and probably most expensive intelligence organisation. It rings the world with intelligence stations, ships, submarines, aircraft and satellites that act as the "platforms" for its global electronic spying operations. It has immense intelligence collecting capabilities. As a remarkable expos, The Puzzle Palace by James Bamford, shows, the NSA is the big brother of all such intelligence organisations in the Western world. Its intelligence links with four especially close allies [Britain, Canada, Australia and New Zealand] are formalised in a highly secret agreement called UKUSA (pronounced "you-koo-za").

Glen Singleton, still in his early 30s, was on a three-year posting to the GCSB. He had grown up and been educated in the city of Cleveland in Ohio. After university study in international relations, he moved to Washington DC to work for the NSA. In late 1984, after settling in as a foreign officer inside the GCSB, he was formally appointed as the GCSB's Deputy Director of Policy and Plans. In this role he advised the GCSB director regularly, directed the work of other GCSB staff and showed overseas visitors around the GCSB. He visited the United States embassy often, travelled to the Defence Signals Directorate (DSD) in Melbourne for meetings and received special private communications from his Washington bosses. Between 1984 and 1987 he would help to make the plans for a period of dramatic expansion of the GCSB's operations and capabilities. Later he would return to the GCSB, having left the NSA, and move into another key role.

Having an American inside the GCSB serving as a foreign liaison officer would be one thing; allowing an officer from another country to direct policy and planning seems extraordinary.

During his first three years on the NSA posting Singleton hosted 50 or more staff from the Wellington intelligence organisations to 4 July parties at his home. But outside intelligence circles, not even the Prime Minister knew of his role. As another former Prime Minister said about the GCSB: "You don't know what you don't know. The whole thing was a bit of an act of faith."

Nineteen eighty-four was a special year for the GCSB. The directors of the five UKUSA agencies meet together once a year to plan and co-ordinate the activities of the global intelligence alliance. The agencies take turns to host the meeting; this year it was the GCSB.1

Throughout the early 1980s the GCSB had been expanding: more than doubling its staff, opening the Tangimoana station and, most pleasing to the director, establishing various new intelligence analysis sections that had given the GCSB more to offer within the alliance.

Five years before, the organisation had been squeezed into a corner of Defence headquarters. Now the flags of the five nations were out on display to greet the UKUSA agency heads to the spacious new Freyberg Building headquarters. After a special welcome for the overseas directors, they met in the 14th floor conference room attached to the director's office, looking out over the pine-clad Wellington hills and, in the foreground, the Stars and Stripes fluttering outside the nearby American embassy.

The most important visitor was Lieutenant-General Lincoln D. Faurer, head of the NSA. With him were Peter Marychurch, head of the British Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ), Peter Hunt, head of the Canadian Communications Security Establishment (CSE), and Tim James, head of the Australian DSD.

Although what was discussed at this meeting is not known, the issues facing the intelligence alliance were clear. The agenda would have included plans for new computer and communications systems, which would help to integrate GCSB operations into the NSA-controlled network, and in particular preparations for a new, super-secret global intelligence system of which New Zealand would be an integral part. It would have been made clear that, as part of the new global system, the NSA required new signals intelligence stations in the South Pacific by the end of the decade to intercept satellite communications. Over the next three years, it would be the job of the GCSB Director, Colin Hanson, and his Australian counterpart to manoeuvre their governments towards approving such a project.

The meeting may also have discussed the nuclear-free issue, which was simmering away as Lange's new Labour government settled into office.

Only a few months later, on 27 February 1985, Lange met a United States State Department official, William Brown, across the dining table of the New Zealand consul general's residence in Los Angeles. It was a short and tense meeting.

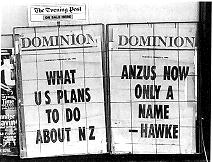

The nuclear-free issue had come to head in New Zealand. Deciding to follow public opinion rather than the advice of its officials, the Labour government had refused entry to the American nuclear-capable warship, USS Buchanan, and now Lange was being read the list of retaliatory measures that would be imposed by the United States government. These included cutting many of the military ties between the two countries; in effect the ANZUS Treaty died that day. And, as part of the reprisals, according to the then Chief of Defence Staff, Sir Ewan Jamieson, "the flow of information [from the United States], on which the New Zealand intelligence community was heavily dependent, was terminated".2

All the journalists, commentators and "well placed sources" were repeating the same message. As far as the public knew, all intelligence ties between New Zealand and the United States were severed.

This was completely untrue. While intelligence from military sources was cut considerably, most of the intelligence flow from the United States continued uninterrupted. The United States government wanted other countries to see New Zealand punished for its nuclear-free policies, but the UKUSA alliance was too valuable to be interrupted by politics.

A few days before Lange's meeting in Los Angeles, the GCSB received a call from its liaison officer at the NSA's headquarters in Washington DC. Warren Tucker, who had moved into the position a few weeks before and would later become Director of Operations back at the GCSB, told the senior GCSB staff that the announcement was coming but reassured them that his position at the NSA was secure. While other New Zealand diplomatic staff in Washington were frozen out by their United States government contacts, Tucker was envied because his position was largely unaffected.

The communications centre (the "commcen") back in the GCSB's Wellington headquarters was the first place where practical signs of the Los Angeles reprisals were noticed. Here mostly ex-Navy communications staff worked around the clock maintaining contact with the four sister agencies.

Every day, hundreds and hundreds of intelligence reports were spat out of the large sound-proofed printers, more reports than the small Wellington intelligence agencies even had time to read. In February 1985, the GCSB was receiving reports about the minute details of the Iran-Iraq War, Soviets in Afghanistan, a weekly list of all the Libyan students in Britain and a lot of other marginally interesting top secret reports. But there was nothing, among the screeds of reports on international terrorism, about the French DGSE agents who were right then on their way to New Zealand to become the first foreign terrorists in New Zealand's history: blowing up the Greenpeace ship Rainbow Warrior.

Most of the daily flood of overseas reports did not stop. But the communications staff noticed that the "routing indicators", which show the origin and destination of documents within the UKUSA system, had been removed from incoming reports. While the public condemnation of New Zealand's nuclear-free policy by the United States government increased in pitch, it seems some strategist in Washington decided there should be no tangible evidence that United States intelligence reports were still arriving in Wellington. They did not want to take the risk that one of these documents might one day be held up in public as evidence that the New Zealand had got away with its nuclear-free policy.

Later, when the public debate had cooled, the usual routing indicators quietly reappeared on the overseas reports. While governments, journalists and the public around the world were led to believe that United States-New Zealand intelligence ties had been cut, inside the five-agency network it was mostly business as usual.

The United States military was unsentimental about its decades of alliance links with the New Zealand armed forces; military exercises, exchanges and other visible links were completely cut. But New Zealand's involvement in the UKUSA intelligence alliance, first alluded to in public by Muldoon only nine months before, was too useful to the overseas allies to be interrupted by a quarrel over nuclear ships.

Notes Chapter 1

1. The meeting was during the second half of 1984, or possibly the start of 1985.

2. Ewan Jamieson, Friend or Ally: New Zealand at odds with its past, Brassey's Australia, Sydney, 1990, p.3.

Captions Chapter 1

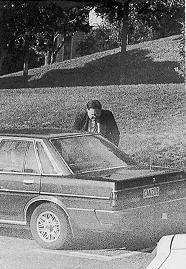

1. Glen Singleton, an American intelligence officer, was Director of Policy and Plans at the GCSB from 1984 to 1987, without government knowledge (pictured arriving at work; note number plate).

2. February 1985 news of severed intelligence links was simply untrue.