Joint Inquiry Staff Statement

Hearing on the Intelligence Community's Response to Past Terrorist Attacks Against the United States from February 1993 to September 2001

Eleanor Hill, Staff Director, Joint Inquiry StaffOctober 8, 2002

Introduction

Mr. Chairman, members of the two Committees, good morning. The purpose of today's hearing is to review past terrorist attacks both successful and unsuccessful -- by al-Qa'ida and other groups against the United States. This review focuses not only on the attacks themselves, but also on how the Intelligence Community changed its posture in response and on broader themes that demand close scrutiny by the Committees. This review of past attacks and issues is not as deep or as thorough as our inquiry into the events of September 11. Instead, it represents a more general assessment of how well the Intelligence Community has adapted to the post-Cold War world, using counterterrorism as a vehicle.

In conjunction with the Joint Inquiry Staff's (JIS's) review of the September 11 attacks, we have reviewed documents related to past attacks and interviewed a range of individuals involved in counter-terrorism in the last decade. The documents include formal and informal "lessons learned" studies undertaken by different components of the Intelligence Community and the U.S. military, briefings and reports prepared by individuals working the threat at the time, and journalistic and scholarly accounts of the attacks. Interviews included officials at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), National Security Agency (NSA), Department of Defense (DoD), National Security Council (NSC), Department of State, outside experts, and other individuals who possess first-hand knowledge of the Intelligence Community's performance or who can offer broader insights into the challenge of counterterrorism.

This Staff Statement is intended to provide the two Committees with lines of inquiry that we believe are worth pursuing with the panelists who will appear before you today. It has four elements. First, we review briefly several major terrorist attacks or plots against the United States at home and abroad. Second, we note several characteristics of the terrorism challenge that became increasingly apparent in the 1990s. Third, we identify a number of important steps taken by U.S. intelligence and other agencies to combat terrorism more effectively, steps that almost certainly saved many lives. Fourth and finally, we describe in detail several problems or issues apparent from past attacks, noting how these hindered the overall U.S. response to terrorism. Several of these issues transcend the Intelligence Community and involve policy issues; others were recognized early on by the Intelligence Community but were not fully resolved.1

-

1 This review is focused on issues that are not addressed fully in other open or closed joint Committee hearings. Thus, for example, important concerns such as information sharing and covert action are not addressed, even though they were important issues in how the Intelligence Community responded to past attacks. This Joint Inquiry Staff has prepared or will prepare assessments of these issues as separate documents.

The Joint Inquiry Staff has reviewed five past terrorist attacks or attempts against the United States as part of its inquiry into September 11: the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center (WTC I); the 1996 attack on the U.S. military barracks Khobar Towers, in Saudi Arabia; the 1998 attacks on U.S. Embassies in Africa; the 1999 "Millennium" plot; and the 2000 attack on U.S.S. Cole.

The Joint Inquiry Staff chose to review these five attacks for several reasons. First, they suggest how the radical Islamist cause grew from a disparate band of relatively unskilled amateurs to a seasoned group of skilled operators. This span of time allows the Joint Inquiry Staff to determine how the Intelligence Community adapted to meet this danger. Second, the attacks represent the major instances of international terrorism against the United States in the decade preceding September 11, 2001. Third, they represent a mix of attacks on U.S. interests at home and abroad. Finally, we included the attack on Khobar Towers to avoid drawing too many lessons from Sunni Islamic extremists linked to al-Qa'ida: as the 19 American dead at Khobar demonstrates, the Lebanese Hezbollah and other groups also threaten American interests today.

A brief review of each incident is provided below.

1993 Attack on the World Trade Center

On February 26, 1993, a truck bomb loded in the B-2 level garage of the World Trade Center in New York City, killing six people and wounding another 1,000. The vehicle was traced to Mohammed Salameh, a Palestinian with Jordanian citizenship. Salameh's arrest led investigators to his accomplices, Arabs of different nationalities who were followers of blind radical Egyptian cleric Omar Abd al-Rahman. Ramzi Yousef, the mastermind of the attack, had already fled the United States and was not apprehended until 1995. Yousef's collaborators, who were far less skilled and professional, were arrested shortly after the bombing.

Several of the radical Islamists responsible for the bombing had conducted terrorist attacks before. Members of New York's Joint Terrorism Task Force (JTTF) traced Salemeh to the home of Ibrahim el-Gabrowny, a cousin of El Sayyid Nosair. Nosair was the shooter in the 1990 assassination in New York City of Rabbi Meir Kahane, the controversial founder of the Jewish Defense League. Nosair also had assistance from Mahmud Abouhamila, who was arrested in connection with the first World Trade Center bombing.

According to FBI officials who were interviewed, the NYPD and the District Attorney's office resisted attempts to label the Kahane assassination a "conspiracy" despite the apparent links to a broader network of radicals. Instead, these organizations reportedly wanted the appearance of speedy justice and a quick resolution to a volatile situation. By arresting Nosair, they felt they had accomplished both. Nosair was shot and then arrested after the Kahane shooting, and a search of his residence uncovered a trove of information regarding his cell's members and activities. Forty-seven boxes of notes and paramilitary manuals were carted away. It would be at least two years before much of the information was actually translated. The FBI case agent says that a relative of Nosair's traveled to Saudi Arabia to obtain money to pay for Nosair's defense. He received funds from a wealthy Saudi, Usama bin Ladin. The agent told the Joint Inquiry Staff that this was the first time the FBI's New York office heard bin Ladin's name.

According to FBI agents interviewed by the Joint Inquiry Staff, intelligence on individual members of the cell who committed the attack was considerable before the World Trade Center attack. In 1989, the FBI had become aware that a number of Americans were being recruited to fight in Afghanistan in the war against the Soviets, a possible violation of the U.S. Neutrality Act. The FBI also learned that these individuals were receiving firearms and martial arts training in the New York area, and the FBI began to surveil these firearms training sessions. The FBI had an informant with access to the cell but, in essence, deactivated him shortly before the bombing. However, there was no indication of the magnitude of the attack they were planning or that they intended to kill thousands of Americans.

After the World Trade Center attack, the FBI reactivated the source who reported on the cell's plans. Drawing on this source, several weeks after the World Trade Center attack, the FBI arrested additional Islamist radicals planning a "day of terror" against several U.S. landmarks. The source enabled the eventual arrest and conviction of Shaykh Abd al-Rahman and his associates for planning the "day of terror."

A senior FBI terrorism analyst told the Joint Inquiry Staff that the lack of a state sponsor of these terrorist activities and the mixture of nationalities involved in the various plots initially confused U.S. investigators. One FBI investigator recalls that he initially suspected Serbian involvement, and later the prevailing opinion was that Libyans were behind the activity. Others thought that perhaps the Iraqis were seeking revenge for Operation Desert Storm. This theory gained support when it was discovered that Ramzi Yousef traveled with a valid Iraqi passport. Over time, however, the Intelligence Community realized that a new phenomenon was emerging: radical Islamic cells, not linked to any country, but united in anti-American zeal.

1996 Attack on Khobar Towers

On June 26, 1996, Saudi Shi'a Muslim terrorists detonated a truck bomb containing 3,000 to 5,000 pounds of explosives on the perimeter of the U.S. apartment complex called Khobar Towers at a military facility in Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. Although the truck did not pass through the base's perimeter security, the bomb's large size, which surprised U.S. officials, led to a massive explosion that destroyed much of the complex. Nineteen Americans died and 500 others were wounded. Following the attack, the United States redeployed its forces to more remote parts of the Kingdom.

A U.S. indictment brought in June 200l charged that the Saudi Hezbollah, with support from Iran, carried out the attack. According to the indictment, Iran and its surrogate, the Lebanese Hezbollah, recruited and trained the bombers, helped direct their surveillance, and assisted in planning the attack.

Warning that U.S. forces were at risk of a terrorist attack was considerable, though detailed information on exactly where or when the attack would occur was lacking. The Intelligence Community warned in a series of briefings and written products that terrorists would seek to strike U.S. forces in Saudi Arabia and that the Khobar Towers complex had been surveilled. As the Task Force led by General Downing that reviewed the attack after the fact noted:

-

Overall, the intelligence provided commanders warning that the terrorist threat to U.S. service members and facilities was increasing. As a result, those responsible for force protection at Khobar Towers and other U.S. government facilities in Saudi Arabia had time and motivation to reduce vulnerabilities.

1998 Embassy Attacks

On August 7, 1998, al-Qa'ida terrorists bombed the U.S. Embassies in Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania. The attacks, which occurred less than ten minutes apart, destroyed the facilities and killed 12 Americans and over 200 Kenyans and Tanzanians. More than 4,000 were injured, many permanently blinded. Local security forces detained several lower-level perpetrators, and others were caught as they fled, leading to important confessions. Four perpetrators were prosecuted in the United States for their role in the bombings. However, several of those who authorized and helped orchestrate the bombings went to Afghanistan or otherwise did not face justice.

Intelligence warning of the attack was limited. The Report of the Accountability Review Boards on the Embassy Bombings in Nairobi and Dar Es Salaam (known as the "Crowe Commission") found that: "[t]here was no credible intelligence that provided immediate or tactical warning of the August 7 bombings." Reporting was imprecise as to location and date, and in contrast to the steady stream of warnings before the Khobar Towers attack the Crowe Commission noted that: "[i]ndeed, for eight months prior to the August 7 bombings, no further intelligence was produced to warn the embassies in Nairobi and Dar Es Salaam." The Intelligence Community quickly determined that al-Qa'ida was responsible for the attacks after they occurred.

Interviews of Intelligence Community personnel suggest that more than any other al-Qa'ida attack before September 11, the near-simultaneous bombing of the Embassies changed how the Intelligence Community perceived the threat of terrorism from that group. Almost all terrorism analysts at all agencies the Joint Inquiry Staff interviewed appear to have recognized that the attacks clearly demonstrated al-Qa'ida's reach, ability to conduct simultaneous attacks, and determination to kill many Americans. Moreover,the attacks indicated al-Qa'ida's patience: planning for the Kenya operation began in 1993. Before these attacks, only small pockets of the U.S. Government recognized the danger al-Qa'ida posed. After the attacks, the danger was far more clearly understood. On August 20, 1998, President Clinton authorized cruise missile strikes on the al-Shifa plant in Sudan and on a terrorist training camp in Afghanistan to retaliate for the bombings. Mr. Berger also testified that the President sought to kill Bin Ladin with the missile strikes, indicating the White House's understanding that Bin Ladin was an adversary who must be eliminated.

Planned Attacks Around the Millennium Celebrations

U.S. customs, law enforcement, and intelligence officers successfully disrupted a series of attacks planned around the Millennium celebrations. On December 13, 1999, an alert U.S. Customs Inspector, pulled over an automobile driven by a 33 year-old Algerian, Ahmed Ressam. Ressam panicked and attempted to flee; he was caught, and inspectors discovered explosives in his car along with a map on which two airports in California and one in Ontario were circled, according to Through Our Enemies' Eyes (Brasseys, 2002), a book by an anonymous senior intelligence official. As Ressam was being arrested and questioned, planned attacks on tourist sites in Jordan were disrupted, and 22 Islamists were eventually convicted of terrorism charges. Ressam was convicted in the United States on terrorism charges in April, 2001.

Following these discoveries, the Intelligence Community and the FBI coordinated a worldwide disruption effort to disrupt other possible attacks. The effort involved dozens of foreign intelligence services that detained suspected radicals in the hopes of gaining confessions or at least keeping them off the streets or intimidating them into aborting any planned attacks. Louis Freeh, the former FBI Director, also related that FBI agents also arrested suspected radicals in the United States for minor violations (often linked to visa problems) and tried to disrupt planned attacks in the United States.

Following the disruption, the Intelligence Community clearly warned senior policy makers that the disruptions only bought time: they did not end the threat of future attacks. Of interest is another attack planned around the Millennium that went undiscovered -- the planned January attack on another Navy warship. The plot failed because the terrorists' boat sank, not because the Intelligence Community disrupted it, and a similar attack was carried out on U.S.S. Cole in October of 2000.

2000 Attack on U.S.S. Cole

On October 12, 2000 al-Qa'ida terrorists piloted a small boat filled with explosives next to the destroyer U.S.S. Cole in the harbor in Aden, Yemen, and detonated it, killing 17 sailors and wounding 39 more. The bombing was the first terrorist attack on a U.S. naval warship.

As with the 1998 Embassy attack, the strike on the Cole involved persistence and planning. Preparations for the attack began in 1998. As noted above, in January 2000, a group of plotters tried to attack another Navy warship. As with other terrorist attacks, several of the leading figures fled Yemen in the days before the bombing. Only the bombers themselves and several relatively poorly trained and unskilled radicals remained.

Peter Bergen, the author of Holy War, Inc. (Free Press, 2001) notes that Yemen had long been a hotbed of radical Islamist activity. Thousands of Yemenis volunteered to fight the Soviets in Afghanistan. Bin Ladin's first attack against the United States occurred against U.S. soldiers transiting Aden en route to Somalia in 1992. During the Yemeni civil war in 1994, the victorious northern regime employed Islamic radicals as shock troops in its attacks on the south. The 3tate Department's 2000 Patterns of Global Terrorism indicates that Yemen was a safe haven for several terrorist groups, including the Egyptian Islamic Jihad -- parts of which, after l998, essentially had become in essence part of al-Qa'ida.

The Intelligence Community provided a steady stream of reporting indicating the danger of a terrorist attack in Yemen, but did not offer specific, actionable intelligence about the U.S.S. Cole attack itself. Other clues -- while falling short of specific warning as to the time, place, and method of the attack -- nevertheless offered considerable information regarding the need for force protection.

A post-attack CIA review, however, found that most of the information provided was quick-turnaround reporting, commentary, and analysis, with little historical context or long-term analysis. A senior DIA terrorism analyst noted in an interview that, in general, there was little effort to question underlying assumptions, such as preconceptions that Bin Ladin would not attack in Yemen because it was an important al-Qa'ida logistics hub or that al-Qa'ida would not strike a Navy ship because of the difficulty of doing so.

A separate inquiry by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence (SSCI) also noted that although intelligence agencies "aggressively collected and promptly disseminated raw intelligence pertaining to terrorist threats," warning products lacked context and analytic depth.

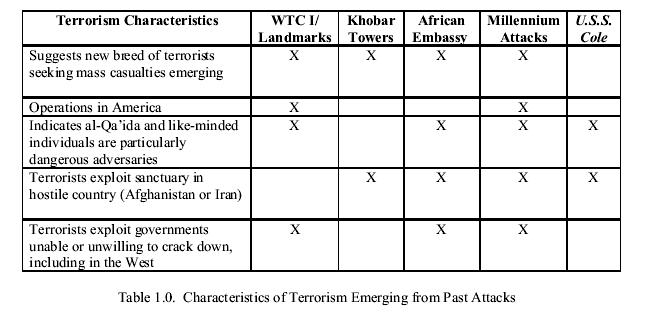

The Joint Inquiry Staff review of the five incidents suggests several important characteristics of the emerging terrorist threat. Some were obvious to all at the time and others only became clear in retrospect, but all required changes in U.S. counterrorism efforts and the Intelligence Community more broadly. The characteristics include:

- The emergence of a new breed of terrorists practicing a new form of terrorism, different from the state-sponsored, limited-casualty terrorism of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s;

- International terrorists who operated in America and were willing to conduct attacks inside America;

- An adversary, al-Qa'ida, that is unusual in its dedication, size, organizational structure, and mission;

- The existence of a sanctuary in Afghanistan that allowed al-Qa'ida to organize, train, proselytize, recruit, raise funds, and grow into a worldwide menace; and

- Exploitation of permissive environments, such as Yemen, where governments were not willing or able to crack down on radical activity.

A New Breed of Terrorism

Throughout the Cold War, radical left-wing groups or ethno-nationalist groups carried out most terrorist acts. The Palestine Liberation Organization, the Abu Nidal Organization, and the Japanese Red Army typified terrorist groups and their tactics. Moreover, many of these groups had state sponsors. Such groups shaped the U.S. government's conception of how a typical terrorist group behaved and the overall U.S. response to terrorism.

The first attack on the World Trade Center was an unambiguous indication that a new form of terrorrism --motivated by religious fanaticism and seeking mass casualties -- was emerging and focused on America. Interviews of FBI personnel who were involved in the 1993 investigation of that attack suggest their initial confusion as to the nature of their new adversary. Arabs from countries hostile to one another worked together. In addition, they had no state sponsor -- something that investigators had assumed they would eventually uncover.

Counterterrorism experts eventually recognized this change and incorporated it into their analysis. For example, a July 1995 National Intelligence Estimate noted a "new breed" of terrorist who did not have a sponsor, was loosely organized, favored an Islamic agenda, and had a penchant for violence. However, despite this recognition, neither the FBI nor the CIA assigned analysts and operators to focus exclusively on these individuals until January 1996.

An emphasis on mass casualties was another important change. Although attacks in the 1980s killed hundreds, no major terrorist group was attempting to kill thousands of civilians. However, a RAND Corporation study indicates that although the number of terrorist attacks decreased in the 1990s, overall casualties per attack increased. Terrorists proved able and willing to kill large numbers of people. This marked a significant change. Brian Jenkins, a foremost expert on terrorism, wrote in 1975 that: "[t]errorists want a lot of people watching and a lot of people listening and not a lot of people dead." Twenty years later, then-Director of Central Intelligence James Woolsey contended that: "[t]oday's terrorists don't want a seat at the table, they want to destroy the table and everyone sitting at it."

The increasing prevalence of religious terrorist organizations contributed directly to this shift. As Bruce Hoffman, a terrorism expert with the RAND Corporation, noted in a statement for the record for the Joint Inquiry: "[f]or the religious terrorist, violence first and foremost is a sacramental act or a divine duty." Ominously, al-Qa'ida began to incorporate suicide attackers -- historically rare among Sunni terrorists -- into its operations with the 1998 Embassy bombings.

This change in lethality was recognized early on within the Intelligence Community and by outside experts and communicated to U.S. government policy-makers. The DCI's December 1998 Declaration of war on al-Qa'ida is only one indication of how seriously the danger of terrorism was taken within the Community. Policymakers from the Clinton and Bush administration have testified that the Intelligence Community repeatedly warned them of the danger al-Qa'ida posed and the urgency of the threat.

However, the strategic implications of this shift in lethality do not appear to have been fully recognized. Terrorism had gone from a nuisance that, though frightening and appalling, killed only hundreds, to a menace that directly threatened the lives of tens of thousands of Americans. Although many of the individuals working on the terrorism problem feared a mass casualty attack, the resources dedicated to the effort against al-Qa'ida remained limited or focused largely on force protection.

Operations in America

The first attack on the World Trade Center in 1993, five years before Bin Ladin openly called on his followers to bring jihad to America, was a painfully clear signal that Sunni extremists sought to kill Americans on American soil. Seven years later, the arrest of Ahmed Ressam should have dispelled doubts that al-Qa'ida and its sympathizers sought to operate on U.S. soil, even though most of the masterminds remained overseas.

The United States itself was also an important location for terrorist logistics. For example, a conspirator in the 1998 Embassy bombings, Wadi el-Hage, a U.S. citizen who had served as Bin Ladin's personal secretary during Bin Ladin's time in Sudan and ran al-Qa'ida's Kenyan operations, lived in the United States over a year before he was arrested in August 1998. FBI agents and Kenyan police had hounded El-Hage from Kenya in August 1997, but he was able to settle in Texas.

Al-Qa'ida: An Unusual and Deadly Adversary

As the 1990s progressed, it became clear that al-Qa'ida was unusual, although not unique, in its skill, dedication, and ability to evolve. The 1993 World Trade Center attack and the plot against U.S. landmarks suggested a group of radical Islamic terrorists who were highly motivated but not particularly sldlled. The 1998 Embassy attack, the planned attack in Jordan around the Millennium, and the attack on U.S.S. Cole, in contrast, suggested an adversary that was highly capable. The 1993 plotters' ambition to kill thousands was frustrated because of limited organizational and financial backing. By the end of the decade, Sunni Islamic extremists had proven themselves highly skilled.

Al-Qa'ida operations before September 11 suggest several traits worthy of concern:

- Long-range planning. The Al-Qa'ida attack on the U.S. Embassies in Africa took five years from its inception. The planning for the attack on U.S.S. Cole took several years;

- Ability to conduct simultaneous operations. The Al-Qa'ida 1998 attack on U.S. Embassies in Africa and the Millennium plots demonstrate that al-Qa'ida was able to conduct simultaneous attacks,suggesting sophisticated overall planning. Hoffinan notes that simultaneous terrorist attacks are rare, as few groups have enough skilled operators, logisticians, and planners;

- Emphasis on operational security. Al Qa'ida's terrorist manuals and training emphasize that operations should be kept secret and details compartmented. Communications security is also stressed. Thus, disrupting these operations is difficult, even if low-level foot soldiers are arrested or make mistakes. Several al-Qa'ida attacks occurred with little warning. Even the successful disruption of part of a plot, as occurred during the Millennium, does not necessarily reveal other planned attacks, such as the planned attack on another U.S. Navy warship around the same time;

- Flexible command structure. As Hoffman notes, al-Qa'ida uses at least four different operational styles, including a top-down approach employing highly-skilled radicals; training amateurs like Richard Reid, the so-called "shoebomber," to conduct simple, but lethal attacks; helping local groups with their own plans, as was done with the Jordanian plotters during the Millennium; and fostering like-minded insurgencies. The tactics that can stop one type of attack do not necessarily work against other plots.

- Imagination. Most terrorists are conservative in their methods, relying on small arms or simple explosives. The attack on U.S.S. Cole, however, was a clear indication of al-Qa'ida's tactical flexibility and willingness to go beyond traditional delivery means and targets.

Although the number of highly skilled and dedicated individuals who have sworn fealty to Bin Ladin is probably in the low hundreds before September 11, the organization as a whole is much larger, with tens of thousands having gone through the training camps in Afghanistan. Its organizational and command structures, which employ many activists who are not formal members of the organization, make it difficult to determine where al-Qa'ida ends and other radical groups begin. Media reports indicate that al-Qa'ida has trained thousands of activists in Sudan and Afghanistan, and interviews of Intelligence officials indicate that al-Qa'ida can draw on thousands of supporters when raising funds, planning, and executing attacks.

The Problem of Sanctuary

The Joint Inquiry Staff review of the five attacks suggests a second characteristic that posed difficulties for the Intelligence Conmmnity and the U.S. government: terrorist exploitation of sanctuaries. Because of these sanctuaries, terrorist masterminds and leading operatives remained oitside America's reach. In addition, terrorists could create an infrastructure of camps to train and recruit, allowing the groups to perpetuate and grow. Finally, terrorists exploited countries friendly -- or at least not hostile -- to the United States to plan operations and gain recruits, and even operate on U.S. soil with limited impunity.

Over many years, the United States worked with dozens of cooperating foreign governments to disrupt al-Qa'ida activities, arrest operatives, and otherwise prevent attacks, but Afghanistan itself was largely a haven. In its Afghan sanctuary, al-Qa'ida built a network for planning attacks, training and vetting recruits, and indoctrinating potential radicals. In essence, al-Qa'ida created a terrorist army in Afghanistan with little interference. Intelligence successes such as the Millennium disruptions and arrests did little to affect this sanctuary.

Although the United States and its allies made numerous arrests following every major terrorist attack, Al-Qa'ida's senior leadership, including many of the masterminds for planning terrorist attacks, remained outside America's reach. The United States did eventually track down Ramzi Yusuf, the mastermind of the first World Trade Center attack, but several of those ultimately responsible for the Embassy bombings and U.S.S. Cole attack have thus far escaped justice.

The 1996 Khobar Towers attack, the 1998 African embassies attacks, and the 2000 U.S.S. Cole attack led the Departments of State and Defense to focus heavily on force protection, but not on meeting the challenge of Afghanistan, even though they recognized the dangers emanating from terrorist camps there. For example, the 2001 Department of Defense report on the U.S.S. Cole attack noted that the U.S. posture in general was too defensive and that "CENTCOM is essentially operating in the midst of a terrorism war."

Sanctuary for terrorists also took a less overt but more pernicious form in friendly countries. The Yemeni government, in contrast to the Taliban's Afghanistan, does not support Islamic radicalism, but terrorists exploited the country as a safe haven in planning the Cole attack due to Sanaa's unwillingness and at times inability to crack down. As became painfully clear after September 11, al-Qa'ida's network extends far beyond Afghanistan and the Middle East. London has long been a hub for Islamic radicals, and much of the planning for September 11 was done in Germany. Al-Qa'ida also raised money and recruited in Asia, Africa, and Europe and in the United States. As Deputy Secretary of Defense Wolfowitz testified, "even worse than the training camps [in Afghanistan] was the training that took place here in the United States and the planning that took place in Germany."

The Intelligence Community and concerned outside experts slowly became aware that effectively countering al-Qa'ida would require confronting the problem of terrorist sanctuary. In an interview, one Counterterrorism Center officer describes the problem of being unable to address the source and only seeing the manifestations as "trying to chopdown a tree by picking the fruit." Similarly, other outside experts warned publicly of the problem of Afghanistan and called for action prior to September 11.

Steps Forward in the Fight Against Terrorism

As these challenges emerged, the Intelligence Community, and at times the U.S. Government, adopted several important measures that increased America's ability to fight terrorism in general and al-Qa'ida in particular. Many of these measures can only be described obliquely or cannot be mentioned at all due to security strictures and rightful concerns about revealing intelligence methods.

Several counterterrorism efforts deserve mention:

- The early creation of a special unit to target Bin Ladin. Well before Bin Ladin became a household name or even well-known to counterterrorist specialists the CTC created a unit dedicated to learn more about Bin Ladin's activities. This unit quickly determined that Bin Ladin was more than a terrorist financier, and it became the U.S. Government's focal point for expertise on and operations against Bin Ladin. Later, after the 1998 Embassy attacks made the threat clearer, the FBI and the NSA increased their focus on al-Qa'ida and on Islamic extremism.

- Innovative legal strategies. In the trial of Shaykh Omar 'Abd al-Rahman, the Department of Justice creatively resurrected the civil war-era charge of "seditious conspiracy," enabling the U. S. Government to prosecute and jail individuals planning terrorist attacks in America.

- Aggressive renditions. Working with a wide array of foreign governments, the CIA helped deliver dozens of suspected terrorists to justice. These renditions often led to confessions and disrupted terrorist plots by shattering cells and removing key individuals.

- Improved use of foreign liaison services. As al-Qa'ida emerged, several CIA officials recognized that traditional U.S. intelligence techniques were of limited value in penetrating and countering the organization. They understood that foreign liaison could act as a tremendous force multiplier and tried to coordinate and streamline what had been an ad hoc process. In addition, the CIA and other Intelligence Community agencies strengthened their liaison relationships. Many al-Qa'ida cells around the world were disrupted as a result of this effort. Former National Security Adviser Berger has testified that cells were disrupted in about 20 countries after 1997.

- Strategic warning on the risk to U.S. interests overseas. After the bombings of U.S. embassies in Kenya and Tanzania in 1998, the CIA clearly and repeatedly provided warnings to senior U.S. policy makers, warnings that reached a crescendo in the summer of 2001. Policymakers from both the Clinton and Bush administrations have testified that the Intelligence Community repeatedly warned them that al-Qa'ida was both capable of and seeking to inflict mass casualties on America.

- Expansion of the FBI overseas. Director Louis Freeh greatly expanded the number of Legal Attache offices and focused them more on countries in which terrorism was prevalent or which were important partners against terrorism. By September 11, there were 44 legal attache offices up from 16 in 1992. Given the increasing role the FBI and the Department of Justice were playing in counterterrorism, these offices helped ensure that domestic and overseas efforts were better coordinated. In addition, they provided the United States with additional access to foreign law enforcement entities, which were often taking the lead on counterterrorism.

- Augmenting the Joint Terrorism Task Forces (JTTFs). The Joint Terrorism Task Force model was originally created to improve coordination between the FBI and the New York Police Department. The first World Trade Center attack led to the expansion of the JTTFs to other cities and led to the inclusion of CIA officers in several task forces.

- Improved information sharing. Intelligence officials and policy makers took several measures to improve information sharing on terrorism among leading U.S. government agencies. The National Security Council revived the interagency process on terrorism and threat warning process, resulting in regular senior policy maker meetings concerning terrorism. The NSA and CIA held regular videoconferences among analysts after the 1998 Embassy bombings. Although many weaknesses remained, the FBI and CIA took steps to increase collaboration, which was extremely poor in the early 1990s, and established rotations in each other's counterterrorism units.

- Streamlined warning at the Defense Department. After the attack on U.S.S. Cole, the Department of Defense subordinated its terrorism analysis capability under the Joint Chief of Staff/Intelligence (J2), which has overall responsibility for warning in the Department of Defense. This reduced confusion and clarified responsibility for warning.

Despite these measures to better fight terrorism, the Intelligence Community response was limited by a number of factors, including interpretations of U.S. law and overall U.S. counterterrorism policy. Among these factors were:

- Continued terrorist sanctuary. Up until September 11, al-Qa'ida raised an army in Afghanistan. In addition, it exploited the laxness of other countries' counterterrorism efforts (or the limits imposed by their legal systems).

- A "law enforcement" approach to terrorism. In part because options such as military force were not promising or deemed feasible, the United States defaulted to countering terrorism primarily through arrests and trials. The government's reliance on a law enforcement approach had several weaknesses, including allowing al-Qa'ida continued sanctuary in Afghanistan.

- Limited FBI aggressiveness at home. The FBI responded unevenly at home, with only some Field Offices devoting significant resources to Islamic extremists. An overall assessment of the risk to America was not prepared, and much of the FBI's counterterrorism effort was concentrated abroad.

- Lack of a coordinated Intelligence Community response. The main intelligence agencies often did not collaborate. In particular, the absence of an effective system for "handoffs" between the FBI, the CIA, and NSA led to a gap in coverage with regard to international threats to the United States itself, an area that should have received particular attention.

- Difficulties in sharing law enforcement and intelligence information. The walls that had developed to separate intelligence and law enforcement often hindered efforts to investigate terrorist operations aggressively.

- Limited changes in intelligence priorities. Counterterrorism became an increasingly important concern for senior Intelligence Community officials, but collection and analytic efforts did not keep pace. Several issues competed with terrorism for attention, and priorities were often not clear.

The Unsolved Problem of Sanctuary

Despite the Intelligence Community's growing recognition that Afghanistan was churning out thousands of radicals, there was little effort to integrate all the instruments of national power -- diplomatic, intelligence, economic, and military -- to address this problem. President Clinton declared after the 1998 bombing that "there will be no sanctuary for terrorists." The CIA and the FBI lacked the means to go after training camps in Afghanistan in a comprehensive manner, but little effort was made to utilize the U.S. military before September 11, with the notable exception of the August 20, 1998 cruise missile strikes.

Both the Clinton and Bush Administrations took some steps to address the problem of Afghanistan. Former National Security Adviser Berger has testified that after August 1998, "the President authorized a series of overt and covert actions to get Bin Ladin and his top lieutenants." None of these actions appear to have hindered terrorist training or al-Qa'ida's ability to operate from Afghanistan. However, Berger also testified that there was little public or Congressional support for an invasion of Afghanistan before September 11, 2001.

Deputy Secretary of State Armitage and Deputy Secretary of Defense Wolfowitz have testified that, by the time of the September 11 attacks, the Bush Administration was far along in a policy review that called for a more aggressive policy against the Taliban and al-Qa'ida in Afghanistan. They were not, however, actively using the military against terrorism before this time.

The problem of permissive environments was understood before September 11, but little was done about it. As the National Commission on Terrorism (the "Bremer Commission") reported in 1998, "[s]ome countries use the rhetoric of counterterrorist cooperation but are unwilling to shoulder their responsibilities in practice, such as restricting the travel of terrorists through their territory." The Commission explicitly mentioned Pakistan and Greece as friendly nations that presented difficulties in regard to terrorism. Although Congress in 1996 authorized the President to designate such countries as "not cooperating fully," this category was seldom applied.

Limited FBI Focus At Home

The FBI increased its focus on terrorism throughout the 1990s, but the Joint Inquiry Staff has found that it did not systematically and thoroughly make the changes necessary to fight terrorism in the United States. The FBI in 1999 made counterterrorism a separate division at headquarters. Changes in the field, however, were slower and less comprehensive.

This mixed record of attention contributed to the United States becoming, in effect, a sanctuary for radical terrorists. As General Brent Scowcroft has testified, "the safest place in the world for a terrorist to be is inside the United States as long as they don't do something that trips them up against our laws, they can do pretty much all they want."

Several observations, taken together, provide support for this contention:

- The leading NSC-level U.S. policy maker with counterterrorism responsibilities contends that, with the exception of the New York Field Office, the FBI field offices around the country were "clueless" with regard to counter-terrorism and al-Qa'ida and did not make them priorities. Former National Security Advisor Berger has testified that the FBI was not sufficiently focused on counterterrorism before September 11.

- FBI officials working on terrorism faced competing priorities, and their ranks

were not augmented. Only one FBI analyst worked strategic analysis exclusively on al-Qa'ida before September 11. The former Chief of the FBI's International Terrorism Section states that he had more than 100 fewer Special Agents working on international terrorism on September 11 than he did in August 1998.

- In the New York Field Office, the office of origin for all major Bin Ladin-related investigations, attention and effort focused primarily on investigating overseas attacks.

- According to FBI officers, FBI training on counterrorism was extremely limited, only increasing after September 11.

- Scowcroft, in testimony to the Joint Committee on September 19, contended that the best FBI agents worked criminal cases, not counterterrorism not linked to traditional criminal work. Dale Watson, former Executive Assistant Director for Counterterrorism and Counterintelligence strongly disagreed with this characterization.

- The FBI did not press the CIA or other intelligence agencies such as NSA for information that might have led to more FBI leads at home.

- An FBI agent with considerable counterterrorism experience noted that foreign governments often knew more about radical Islamist activity in the United States than did the U.S. Government because these governments saw this activity as a threat to their own power.

Attention to terrorist activity in the United States often increased after an attack when the links between radicals in the United States and overseas became better known. For example, Watson says that he only knew of three al-Qa'ida suspects in the United States before the 1998 Africa Embassy bombings, but some 200 FBI counterterrorism cases were opened after the bombing.

FBI officials argue, however, that al-Qa'ida proved a difficult target in the United States. Director Freeh notes that al-Qa'ida operations were small an were not connected to real "cells" -- a judgment echoed by several senior FBI investigators. These investigators claim that "international radical fundamentalists" operate in the United States but that real al-Qa'ida members -- those involved in planning or carrying out attacks -- avoid other radicals and stay clear of radical mosques as part of their tradecraft.

Joint Inquiry Staff investigators received mixed reports on the FBI's aggressiveness in penetrating radical Islamic groups in the United States. Sources proved invaluable in the successful prevention of the 1993 attack on New York landmarks and for the prosecution of the first World Trade Center attack. In addition, the FBI had numerous wiretaps and several human informants in its effort to target various radical Islamist organizations. However, an FBI official involved in the investigations of the first World Trade Center attack and other terrorist plots notes that the Bureau made it exceptionally difficult to handle sources (as opposed to working with cooperating witnesses), a difficulty that increased in the 1990s. The agent contends that the FBI did not want to be associated with persons engaged in questionable activities, even though they can provide solid information. In addition, he advised that individual agent performance ratings downgraded the importance of developing informants.

The FBI also did not inform policy makers of the extent of terrorist activity in the United States. Former National Security Advisor Berger has testified that the FBI assured him that there was little radical activity in the United States and that this activity was "fully covered." Although the FBI conducted many investigations, senior FBI officials and analysts did not accumulate these pieces into a larger picture.

The FBI's limited attention to the danger at home reflects a huge gap in the U.S. Government's counterterrorism structure: a lack of focus on how an international terrorist group might target the United States itself. No agency appears to have been responsible for regularly assessing the threat to the homeland. In his testimony before the Joint Committee on September 19, Deputy Secretary of Defense Wolfowitz asserted that an attack on the United States fell between the cracks in the U.S. Intelligence Community's division of labor. He noted that "there is a problem of where responsibility is assigned." The CIA and the NSA followed events overseas, and their employees saw their job as passing relevant threat information to the FBI. The FBI, on the other hand, does not have the analytic capacity to prepare assessments of U.S. vulnerability and relies heavily on the CIA for much of its analysis.

In addition, prior to September 11, FBI Field Offices usually did not initiate investigations on individuals believed to be permanently outside of the United States. There were no legal barriers that prevented such an investigation, but one FBI field agent claimed that FBI Headquarters discouraged such investigations. In such cases, it was within the discretion of the case agent whether to inform the CIA, Immigration and Naturalization Service, State Department, or other agencies about the agent's investigative interest. As a result, the agent told the Joint Inquiry Staff that the FBI often did not learn when suspects returned to the United States.

Law Enforcement: A Problematic Approach to Counterterrorism

The perpetrators of the 1993 World Trade Center plot and the attack on New York landmarks, and several of those involved in the 1998 Embassy bombing, as well as other plots were all prosecuted. This emphasis on prosecution continues a trend begun in the 1980s, when Congress and President Reagan gave the FBI an important role in countering international terrorism, including events overseas.

U.S. Government officials apparently never intended to rely exclusively on law enforcement to fight terrorism. By default, however, law enforcement tools became the primary instrument of American counterterrorism strategy. Senior Department of Justice officials including Mary Jo White, who as U.S. Attorney in the Southern District of New York prosecuted most of the most important ases against al-Qa'ida, point out that they saw their efforts as an adjunct to other means of fighting terrorism.

In addition, the law was often used to disrupt the activities of suspect terrorists in the United States. If appropriate, U.S. Attorney offices prosecuted individuals for perjury, passport fraud, and other crimes in an effort to splinter the broader terrorism support network. White favored using the law against individuals for "spitting on the sidewalk"-type of crimes if they were suspected terrorists.

Prosecutions do have several advantages in the fight against terrorism. As White noted, prosecutions take terrorists off the street. She acknowledges that this does not shut down an entire group, but some bombs do not go off as a result of the arrests. In addition, critical intelligence often comes from the investigative process, as individual terrorists confess or reveal associates through their personal effects and communications. As former FBI Director Louis Freeh pointed out, "you can't divorce arrest from prevention." White also contends that the prosecutions may deter some, though not all, individuals from using violence. Finally, the threat of a jail sentence often induces terrorists to cooperate with investigators and provide information.

Heavy reliance on law enforcement, however, also has costs. As Pillar notes, it is easier to arrest underlings than masterminds. Those who organize and plan attacks, particularly the ultimate decision makers who authorize them, are often thousands of miles away when an attack is carried out. In addition, the deterrent effect of imprisonment is often minimal, particularly for highly motivated terrorists such as those in al-Qa'ida. Moreover, law enforcement is time-consuming. The CIA and the FBI expended considerable resources supporting investigations in Africa and in Yemen regarding the Embassies and U.S.S. Cole attacks, a drain on scarce manpower and resources that could have been used to gather information and disrupt future attacks. Finally, law enforcement standards of evidence are high: making a case that meets these standards often requires unattainable intelligence and compromises sensitive sources or methods.

At times, law enforcement and intelligence have competing interests. The former head of the FBI's international terrorism division notes that Attorney General Reno leaned toward closing down FISA surveillance if they hindered criminal cases. White, however, notes that the need for intelligence was balanced with the effort to arrest and prosecute terrorists. In addition, as noted earlier, convictions that help disrupt terrorists are often on minor charges (such as immigration violations), which do not always convince Field Office personnel that the effort is worthwhile compared with putting criminals in jail for many years. As former FBI Executive Assistant Director for Counterterrorism and Counterintelligence Dale Watson explains, Special Agents in Charge of FBI Field Offices focused more on convicting than on disrupting.

The reliance on law enforcement when individuals have fled to a hostile country such as Iran or the Taliban's Afghanistan appears particularly ineffective, as the masterminds are often beyond the reach of justice. One FBI agent scorns the idea of using the Bureau to take the lead in countering al-Qa'ida, noting that all the FBI can do is arrest and prosecute. They cannot shut down training camps in hostile countries. He notes that, "[it] is like telling the FBI after Pearl Harbor, 'go to Tokyo and arrest the Emperor.'" In his opinion, a military solution was necessary because, "[t]he Southern District doesn't have any cruise missiles."

Before September 11, the United States did not regularly use military force against terrorists. However, senior policy makers have suggested that the policy community did not see a sustained military campaign against terrorist infrastructure in Afghanistan as politically feasible. Moreover, the U.S. military reportedly did not believe it should take the lead on counterterrorism before September 11.

Lack of a Coordinated Intelligence Community Response

Counterterrorism, like other transnational threats such as drug trafficking, requires close coordination among domestically and internationally focused intelligence agencies. However, each of the principal collectors of counterterrorism intelligence -- the FBI, the CIA, and the NSA -- has distinct missions, distinct sets of legal authorities and restraints, and distinct cultures that can hinder collaboration. Throughout the Cold War, it was acceptable to divide responsibilities depending on whether a threat was abroad or located in the United States. Indeed, repercussions from the collaboration between the three agencies against perceived domestic security threats associated with anti-Vietnam War protests in the 1960s and 1970s reinforced the importance of this division of responsibility.

As the 1990s progressed, coordination in general improved as the different agencies became aware of each other's requirements and limits. For example, in one late 1990s operation, information was obtained through intelligence channels and could not be used in a criminal prosecution because the chain of custody did not involve U.S. law enforcement officials. However, by 2001 greater cooperation between intelligence and law enforcement agencies better addressed such issues.

Despite several such positive steps, there was only a limited effort to act in a unified manner as a Community, rather than as a loose collection of distinct agencies. Even after the 1993 World Trade Center attack, the Millennium plot, and links to the United States in the 1998 Embassy attacks revealed that Islamic extremists had a global network that included the United States, there does not appear to have been any significant sustained attempt by the FBI, the NSA, and the CIA to work together to collect information about the contacts between foreign persons in the United States and foreigners abroad.

Several problems noted in interviews suggest a lack of integration:

- Not all JTTFs included CIA officers, hindering a thorough and smooth dissemination of information among international, national, and local agencies with counterterrorism responsibilities. Of the 35 JTTFs active on September 11, only six had CIA officers on them.

- At times, agencies did not disseminate information due to a lack of recognition of its value to other parts of the Intelligence Community. Details and fragments from communications, operations officers, FBI investigators, and others often were not passed on. This was not, in general, due to "turf" issues or a deliberate intention to hinder counterterrorism, but rather due to a failure to recognize that this information was wanted.

- Information was often shared among institutions but did not necessarily flow to those who most needed it.

- Poor information systems and the high level of classification, prevented FBI field officers from using NSA and CIA data.

- Senior management often appears unaware of information sharing problems. Former FBI Director Louis Freeh state that all intelligence was provided to the CIA and that there was no problem with the amount of such information or the level at which this transfer of information was taking place, an assertion that individuals at the working level at the CIA strongly contest; and

- When investigating radicals in the United States, the FBI faces legal and regulatory restrictions (discussed further below) on the dissemination of information to intelligence agencies obtained in the course of FBI investigations in the United States.

Even the CTC, the Intelligence Community's counterterrorism organization that was expressly designed to foster a Community-wide response, suffered from parochialism. The creation in 1986 of the DCI's Counterterrorist Center was a vital step in the United States effort against terrorism. Fifteen years after its creation, it had grown and integrated other parts of the Intelligence Community, including the FBI and NSA. Rotations to the CTC from other Agencies helped improve cooperation, as did a growing recognition of the value of different forms of reporting. Yet the CTC still remained largely a CIA organization closely tied to the Directorate of Operations. The Center's location at the CIA reinforced this perception. Interviews at the NSA, DIA, and FBI indicate that many officials there saw the CTC primarily as a CIA rather than a community organization. It was not clear whether rotational personnel from other agencies were meant to perform duties of CTC officers, act solely as liaison with their home agencies, or do both. As a result, the CTC did not always lead the Intelligence Community as a whole or foster collaboration.

The net effect of these problems was gaps in the collection and analysis of information about individuals and groups operating both in the United States and abroad. The actions of those responsible for the attacks of September 11 demonstrate why effective integration of domestic and foreign collection is critical in understanding fully the operations of international terrorists. We now know that several hijackers communicated extensively abroad after arriving in the United States and at least two entered, left, and returned to the United States. Effective tracking of their activities, which would have required coordination among the agencies, might have provided important additional information.

Priorities Often Not Updated

Starting in 1995, the Intelligence Community's strategic-level guidance for national security priorities was set by Presidential Decision Directive (PDD)-35. In an attempt to rank the myriad of post-Cold War threats facing the United States, PDD-35 established a tier system. Unfortunately, the tiers were broad and overly concentrated at the upper levels (e.g., there were both Tier 1A and Tier 1B priorities). Moreover, PDD 35 was never amended despite language that required an annual review. As certain threats, including terrorism, increased in the late 1990s, none of the "lower level" Tier 1 priorities were down-graded so that resources (money and people) could be reallocated. To much of the Intelligence Comnmnity, everything was a priority -- the U.S. wanted to know everything about everything all the time.

The vagueness of PDD-35 quickly translated into an overburdened requirements system within the Intelligence Community. For example, NSA analysts acknowledged that they had far too many broad requirements (some 1,500 formal ones) that covered virtually every situation and target. Within these 1,500 formal requirements, there were almost 200,000 "Essential Elements of Information" (EEI) that were mandated by customers. Analysts understood the gross priorities and worked the requirements that were practicable on any given day. However, several have acknowledged that, in some cases, the priority demands precluded them from delving deeply into certain areas.

The Wall

Previous Staff Statements have described a variety of situations in which significant information was not shared between personnel from different Intelligence Community agencies, or between the agencies themselves, or between those agencies and organizations outside the Intelligence Community. While some of these episodes may be traced to the press of business and the fast pace of counter terrorism operations, most have been described to the Joint Inquiry Staff in terms that relate to the many "walls" that have been built between the agencies over the past sixty years as a result of a variety of legal, policy, institutional, and individual factors. Several prominent commissions, including those led by Ambassador Bremer and Governor Gilmore, have noted the difficulties caused by the Wall and called on the Attorney General to minimize problems whenever possible by clarifying procedures and expediting information sharing.

The walls in question include those that separated foreign activities from domestic activities, foreign intelligence operations from law enforcement operations, the FBI from the CIA, communications intelligence from other types of intelligence, Intelligence Community agencies from other federal agencies, classified national security information from other forms of evidentiary information, and information derived from electronic surveillance for foreign intelligence or criminal purposes from those who are not directly involved in its collection. A brief summary of the sources and substance of several of these walls is necessary to understand the difficulties they have caused and the nature of any effort to alter them.

Following the end of World War II, the National Security Act of 1947 created the United States' first peacetime civilian intelligence organization, the Central Intelligence Agency. Two fundamental considerations shaped that act: that the United States not enable a Gestapo-like organization that coupled foreign intelligence and domestic intelligence functions; and that the domestic jurisdiction of the Federal Bureau of Investigation be preserved. In order to satisfy these two considerations, the Act provided that the CIA should have no police, subpoena, or law enforcement powers, and should not perform any internal security functions.

Generations of intelligence professionals have been trained in this distinction, the doctrine of disclosing information only to those who have a demonstrable "need to know," and the rigidities of the national security classification system. On the law enforcement side, it has long been recognized that confidentiality, protection of witnesses, and secrecy of grand jury information are essential to the successful investigation and prosecution of crimes. Thus, to both the law enforcement and foreign intelligence professions, proper security practices and strict limits on the sharing of information are second nature.

By the mid-1970s, however, the law nforcenient interest in disclosing evidence to prosecute and convict gradually came to prevail over the foreign intelligence interest in maintaining secrets. This most often occurred in the context of an espionage investigation where the mutual interest in successful prosecution would force the two sides to come together temporarily, often with great friction, and craft special procedures to limit the exposure of intelligence information in the case, but yet produce sufficient evidence to convict the defendant. This culminated in the Classified Information Procedures Act of 1980 that established a statutory framework for the use and protection of classified information in criminal proceedings.

Most of the day-to-day differences in practice and procedure were cloaked from public discussion because of the need for confidentiality on the one hand and secrecy on the other. However, the foreign intelligence/law enforcement division of authority, activity, and access over this thirty year period are best illustrated by the development of separate paths for law enforcement- and foreign intelligence-related electronic surveillance and searches, an area where Constitutional and jurisprudential factors require a firm public legal basis.

The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution requires a judicial warrant for most physical searches for law enforcement purposes. In 1967, the Supreme Court decided that law enforcement officers engaged in electronic surveillance for criminal investigative purposes also should be required by the Constitution to obtain a warrant based upon probable cause to believe a crime is being committed. Congress established such standards for obtaining such judicial warrants in 1968.

That 1967 Supreme Court decision expressly reserved the question of whether electronic surveillance for foreign intelligence purposes also required a warrant from a judge. A Supreme Court case in l972 drew the limits of this practice by holding that the activities of a domestic group could not be subjected to warrantless electronic surveillance authorized by the President or Attorney General unless the executive branch could establish a connection between the group and a foreign power. The Government's assertion that such surveillance was necessary in order to collect intelligence about the group as part of an "internal security" or "domestic security" investigation was not sufficient to override the Constitutional requirement for a warrant. The Court did not address "the scope of the President's surveillance power with respect to the activities of foreign powers within or without the country."

A few years later, Congress conducted extensive investigations into the activities of the U.S. intelligence agencies. These activities included warrantless electronic surveillance of U.S. citizens who were not agents of any foreign power and warrantless physical searches within the United States conducted in the name of protecting intelligence sources and methods. Based on these findings and the Supreme Court's 1972 suggestion, Congress and the Executive branch agreed on the enactment of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act in 1978.

The FISA established a special court that was designed to meet the various points the Government had relied upon in the past to argue that the courts were not equipped to authorize foreign intelligence-related surveillances. Also, instead of probable cause to believe a crime is being committed, the Act required the Government to demonstrate probable cause that the target is a foreign power or agent of a foreign power and is engaged in clandestine intelligence activities or international terrorism and, where the target is a U.S. person, that the person's activities involve or may involve a violation of U.S. criminal laws. Recognizing that intelligence and law enforcement interests would coincide in many cases where foreign intelligence surveillance is appropriate, such as espionage and terrorism investigations, the Act permits information produced by the surveillance to be shared with law enforcement personnel. It also provides procedures by which such information may be tested and used in prosecutions. However, to ensure that the division between foreign intelligence- and law enforcement-related electronic surveillance was maintained, the Act required a certification that "the purpose" of a proposed FISA surveillance be the collection of foreign intelligence information.

As the 1980s began, the law enforcement and intelligence communities worked together most often in the context of counterintelligence investigations and counternarcotics programs. The law enforcement agencies became more acutely aware in the course of this collaboration of the evidentiary complications that could arise as a result of using intelligence in their law enforcement efforts. For example, defense attorneys pursuing discovery of all investigative information relating to the guilt or innocence of their clients could move to have charges dismissed if information was withheld by the Government on the basis of national security classification.

This increased interaction also required that the intelligence agencies devise creative ways to disseminate intelligence for law enforcement use while protecting intelligence sources and methods. Intelligence agencies began reporting information in special formats (i.e., "tearlines") to allow less classified or unclassified versions of intelligence to be separated from the more highly classified portions and shared with law enforcement personnel. They also provided intelligence information in classified form to law enforcement organizations "for lead purposes only" so as to allow law enforcement organizations to take action on the information while preventing it from becoming entwined in criminal investigations.

In addition, individuals in the Justice Department and United States Attorneys' Offices began to be designated as focal points for intelligence reporting. These officials were given the responsibility of insulating law enforcement and prosecutive personnel from intelligence information and finding ways to allow them to benefit from it without incorporating it into their case files. These arrangements began to be generically referred to as "walls."

An additional form of "wall" was developing at the Department of Justice in connection with FISA electronic surveillances and physical searches for intelligence purposes. In order to avoid courts ruling that FISA surveillances were illegal because foreign intelligence was not their "primary purpose," DOJ lawyers began to limit contacts between FBI personnel involved in these activities and FBI and DOJ personnel involved in criminal investigations.

The Attorney General issued special procedures in 1995 regulating such contacts in FBI foreign intelligence investigations where FISA was being used and potential criminal activity was discovered. These procedures required three-way notice and coordination between the FBI, DOJ's Criminal Division and DOJ's Office of Intelligence Policy and Review (OIPR). These procedures were augmented by the Attorney General in 2000 and 2001 and were actually adopted and incorporated by the FLSA Court in FISA surveillances that it approved after November 2001.

The wall in FISA matters became thicker and higher over time, as is explained in the May 17, 2002 opinion of the FISA Court rejecting proposed changes in the procedure by the Attorney General:

-

.... to preserve ... the appearance and the fact that FISA [was] not being used sub rosa for criminal investigations, the Court routinely approved the use of information screening "walls" proposed by the government in its applications. Under the normal "wall" procedures, where there were separate intelligence and criminal investigations, or a single counter-espionage investigation with overlapping intelligence and criminal interests, FBI criminal investigators and [DOJ] prosecutors were not allowed to review all of the raw FISA [information] lest they become de facto partners in the FISA [operations]. Instead, a screening mechanism, or person, usually the chief legal counsel in an FBI field office, or an assistant U.S. attorney not involved in the overlapping criminal investigation, would review all of the raw [information] and pass on only that information which might be relevant evidence. In unusual cases . . . , [DOJ] lawyers in OIPR acted as the "wall." In significant cases,. . . such as the bombings of the U.S. embassies in Africa,. . . where criminal investigations of FISA targets were being conducted concurrently, and prosecution was likely, this Court became the "wall" so that FISA information could not be disseminated to criminal prosecutors without the Court's approval.

The consequences of the FISA Court's approach to the Wall between intelligence gathering and law enforcement prior to September 11 were extensive. FBI personnel feared suffering the same fate as the agent who had been barred. FBI personnel who were involved in FISA matters began to avoid even the most pedestrian contacts with the criminal side of the FBI or DOJ since such contacts could result in intensive scrutiny by OIPR and the FISA Court. NSA, unable to be certain that it could identify which of its reporting came from FISA authorizations and which did not, began to indicate on all its reporting that the content could not be shared with law enforcement personnel without the prior approval of the FISA Court. In addition, field agents complained that getting a FISA approved was time-consuming.

The various types of walls have had other consequences as well, including specific examples of direct relevance to this inquiry. For example, a CIA employee advised two FBI employees in January 2000 regarding what the CIA knew about the activities of future hijacker Khalid al-Mihdhar in Malaysia, but not the fact that al-Mihdhar had a multiple entry U.S. visa. The CIA officer stated in an e-mail at the time that the FBI would be brought "into the loop" immediately as soon as "something concrete" was developed "leading us to the criminal arena or to known FBI cases." Perhaps reflecting the deadening effect of the long standing wall between CIA and FBI, the FBI agents reportedly thanked the CIA employee and "stated that this was a fine approach" even though the FISA wall did not apply in this case.

Even in late August 2001, when the CIA advised the FBI, State Department, INS, and Customs that al-Mihdhar, al-Hazmi, and two other "Bin Laden-related individuals" were in the United States, FBI headquarters refused to accede to the New York field office's recommendation that a criminal investigation be opened, which would allow greater resources to be dedicated to the search for al-Mlhdhar. This was based on the reluctance of FBI headquarters to utilize intelligence information to draw the connection between al-Mihdhar and U.S.S. Cole bombing that would be necessary for a criminal investigation. FBI headquarters lawyers took the position that criminal investigators "CAN NOT" be involved and that any substantial criminal information that might be discovered would be "passed over the wall" according to proper procedures. Again, the FBI apparently applied the FISA "wall" procedures to a non-FISA case.

When the FBI contacted INS and the State Department's Diplomatic Security Bureau to seek visa information regarding al-Mihdhar and al-Hazmi, the Bureau did not share with the other organizations the intelligence information that was the basis for the request. Both the INS and the State Department say they would have been able to bring their informational and personnel resources to bear with greater chances of success if they had been told the emergency nature of the search.

The USA PATRIOT Act provided unambiguous authority for the Attorney General and other law enforcement officials to disclose to the Director of Central Intelligence any foreign intelligence collected in the course of a criminal investigation. The Act also amended the requirement that intelligence be "the purpose" of a FISA search. Since Congress emended FISA, the FISA Court rejected DOJ rules that would have allowed the Criminal Division to direct or control FISA cases -- the DOJ has appealed that ruling. This was intended to reduce, if not remove altogether, the wall that has grown up around FISA operations. The USA PATRIOT Act also amended the Rules of Criminal procedure to allow foreign intelligence developed in grand jury proceedings to be shared with non-law enforcement personnel. Another amendment permits information from law enforcement electronic surveillances to be shared with non-law enforcement personnel.

These changes to the law, and the shock of September 11 itself, have had some beneficial impacts on the ability and willingness of the Intelligence agencies and their personnel to share information with one another and with non-Intelligence Community agencies and personnel. Whether and to what extent this impact can be sustained remains to be seen.

As this review suggests, the Intelligence Community made several impressive advances in fighting terrorism since the end of the Cold War, but many fundamental steps were not taken. Individual components of the Community scored impressive successes or strengthened their effort against terrorism, but important gaps remained. These included many problems outside the control or responsibility of the Intelligence Community, such as the sanctuary terrorists enjoyed in Afghanistan and legal limits on information sharing between intelligence and law enforcement officials.

However, another major contributing factor was that the Intelligence Community did not fully learn the lessons of past attacks. On September 11, 2001 al-Qa'ida was able to exploit the gaps in the U.S. counterterrorism structure, some of which were remediable, to carry out its devastating attacks.