The need for intelligence and for a capability within the U.S. government to collect, produce, and disseminate it remains critical. The end of the Cold War has not ushered in an age of peace and security. Nor is the need for intelligence eliminated by new sources of open information. There are still important but hard to learn facts about targets-including the intentions and capabilities of rogue states and terrorists, the proliferation of unconventional weapons, and the disposition of potentially hostile military forces-that can only be identified, monitored, and measured through dedicated intelligence assets.

The ultimate purpose of U.S. intelligence is to enhance U.S. national security by informing policymakers and supporting military operations. Toward these ends, one of the most important functions of the intelligence community is to provide analysis gleane d from all sources (open and secret) and to package it in a timely and useful manner. Only the intelligence community performs this essential integrative function.

A large budgetary"peace dividend" in the intelligence area is unlikely. Although there should be opportunities for savings-reducing redundancies within and between agencies, introducing efficiencies, restraining over-tasking, devoting less effort to the f ormer Soviet Union and Eastern Europe-modern systems for collection remain expensive. Moreover, the need to collect and assess information for a wide array of tasks is not fading. Accurate intelligence significantly enhances the effectiveness of diplomati c and military undertakings; while good intelligence cannot guarantee good policy, poor intelligence frequently contributes to policy failure. The United States will have to continue to devote significant resources if it desires a significant capability.

Last, it is important to keep in mind that no amount of redesign or regulation can compensate for poor leadership. It will fall upon current and future senior officials of the intelligence community to make the development of management skills a priority and promote a culture in which excellence is rewarded, talent is developed, quality is valued, legitimate risk-taking is encouraged, and respect for the law is unquestioned. Those entrusted with oversight are responsible for fostering such an environment.

The recommendations of this Task Force fall under three headings: measures to improve the intelligence product, suggestions for internal reorganization, and steps to build or rebuild relationships with important external constituencies.

Improving the Product

The process by which intelligence requirements and priorities are established warrants overhaul. Requirements for both collection and analysis should be heavily influenced by the needs of policymakers, an imperative that argues against suggestions to isol ate the collection agencies further or increase their autonomy. At the same time, some sort of market constraint, under which intelligence consumers can only receive so much free intelligence before their own agency has to find resources to support a grea ter intelligence effort, should be introduced.

Prioritization is a must. The highest priorities for U.S. intelligence collection-and, in most cases, analysis-for the foreseeable future include the following: the status of nuclear weapons and materials in the former Soviet Union; developments in Iraq, Iran, and North Korea; potential terrorism against U.S. targets in the continental United States and overseas; unconventional weapons proliferation; and political and military developments in China. Other targets could be added to this list temporarily if , for example, U.S. forces were to be deployed in significant numbers.

There is also a need for economic intelligence, although the Task Force could not agree on how aggressively the United States should collect information on its major economic partners or on how much to emphasize analysis of economic issues. There was agre ement that economic intelligence should not be used offensively to help a U.S. firm win a contract against foreign competition, but should be used defensively to alert policymakers when bribes or other unfair practices are being used against an American f irm. Counterintelligence was deemed appropriate to help protect U.S. firms from the espionage efforts of foreign firms and governments.

The need to insulate intelligence from political pressure is a powerful argument for maintaining a strong, centralized capability and not leaving intelligence bearing on national concern up to individual policymaking departments. Competitive analysis of c ontroversial questions can also help guard against politicization, as can Congress and the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board (PFIAB). Competitive or redundant analysis needs to be carried out and conveyed to policymakers in those areas where being wrong can have major consequences. The leaders of the intelligence community must reinforce the ethic that speaking the truth to those in power is required-and defend anyone who comes under criticism for so doing.

The best way to ensure high-quality analysis is to bring high quality analysts into the process. Analysis would be improved by increasing the flow of talented people into the intelligence community from outside the government. Greater provision should be made for lateral and mid-career entry of such analysts as well as for their short-term involvement in specific projects. Closer ties between universities and the intelligence community is desirable in this regard. Careerists would benefit from greater opp ortunities to spend time in other departments and nongovernmental organizations, including those involved in commerce and finance.

Emphasis on long-term estimates of familiar subjects and broad trends should be reduced, given the lack of customer interest and the low comparative advantage of the intelligence community in this realm. Any such estimates ought to be short, written by in dividuals, and have sources identified where they lead to major conclusions. Areas of consensus and disagreement alike should be highlighted in group projects.

The intelligence community should make maximum use of open sources, but it should not become an all-purpose source of information or think tank for either the executive branch or Congress. Individual agencies and departments should try to fulfil their own information needs by developing an in-house capability or exploiting what is available in the private sector.

Internal Changes

The position of the Director of Central Intelligence should be strengthened so that the DCI can wield greater influence over the various components of the intelligence community. Greater centralization promises to bring about high-quality, coordinated ana lysis and make resource decisions that reflect national priorities, not choices driven largely by those who oversee the technical collection programs or who are concerned with military programs alone. The Task Force believes the dangers of such a reform c an be offset by establishing an appeals mechanism for serious disagreements over budget and policy and by instituting sufficient oversight.

The Task Force does not favor appointing the DCI for a fixed and lengthy term. What is most important is that a president respect and feel comfortable with his principal intelligence adviser. If that is not the case, there is a risk that intelligence will be ignored.

The most important function for the clandestine services is the collection of human intelligence, that is, espionage. Such intelligence can complement other sources and, especially in closed societies, be the principal or sole source of information. In so doing, it will at times prove necessary to associate the United States with unsavory individuals, including some who have committed crimes. This is acceptable so long as the likely benefits for policy outweigh the moral and political costs of the associa tion.

The capability to undertake covert action is an important national security tool, one that can provide policymakers a valuable alternative or complement to other policies, including diplomacy, sanctions, and military intervention. Building a capacity for both espionage and covert action takes time and resources; nurturing such a clandestine capability ought to be one of the highest priorities of the intelligence community. Constraints on clandestine activity need to be reviewed periodically to ensure that they do not unduly limit the effectiveness of this tool.

The leadership of the CIA must strive to oversee the Directorate of Operations without stifling initiative. Oversight should require that the DO is performing quality work consistent with policy priorities; senior officials are kept informed of activities ; the activities are consistent with the law and relevant regulations; the DO is treating its employees responsibly; and analysts outside the directorate have full access to the DO's product. In return, those in the DO should know that risk-taking will be supported (and officers will be politically protected) so long as what they do is authorized and legal under U.S. law at the time.

The secretary of Defense, working closely with the DCI and the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, should undertake a full review of existing arrangements and implement necessary reforms as soon as possible to bring about a clearer division of labor am ong the military services, the JCS, the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA), the commanders in the field, and the office of the secretary of Defense so that unnecessary redundancies are avoided.

The president and the DCI should consider creating an intelligence reserve corps for dealing with unanticipated crises in low priority areas so that constrained resources can be concentrated on the most important targets. Such a corps could consist of for mer intelligence professionals, academics, and others with particular geographic and/or functional expertise.

Building and Rebuilding Critical Relationships

The president, drawing on his principal policy advisers, and working closely with the DCI and other members of the intelligence community, the bipartisan leadership of Congress, and members of both the Aspin-Brown Commission and the PFIAB, needs to make r eform of the intelligence community a major national security priority. A steering group ought to be established once the Aspin-Brown Commission has completed its work to coordinate reform.

Intelligence sharing is an important tool that can enable others, be they friendly governments or U.N. agencies, to be more effective actors and partners. Such sharing of intelligence ought to be maintained and even expanded so long as the United States d erives clear benefits and security is not compromised.

Foreign policy normally ought to take precedence over law enforcement overseas. FBI and Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) agents operating abroad should not be allowed to act independently of the ambassador or the CIA lest pursuit of evidence or individuals f or prosecution causes major foreign policy problems or complicates ongoing intelligence and diplomatic efforts. The complex subject of relations between intelligence and law enforcement agencies is a good candidate for additional review and reform.

Congressional oversight of the intelligence community is essential in a democracy. Such oversight is more constructive when it focuses on policy initiatives, such as reorganizing the intelligence community, and evaluation of existing programs and policies , rather than on attempting to manage current operations. Merging relevant committees for briefings and hearings would reduce the burden on administration officials without weakening oversight. Limits on how long any member can serve on an intelligence co mmittee should be removed to deepen congressional expertise.

Annual funding for the intelligence community should be declassified, as should information on basic elements of the intelligence program. Even more than is the case with the U.S. defense budget, however, large areas of spending will need to remain classi fied to protect sensitive undertakings and to avoid discouraging other intelligence services from working with the United States.

The Council on Foreign Relations Task Force on the Future of U.S. Intelligence was established in early 1995 with the purpose of assessing the need for intelligence in the post-Cold War world and how the U.S. government should go about meeting it. All Tas k Force members realized that this goal was a moving target given the changes now underway throughout the intelligence community, the appointment of a new Director of Central Intelligence, the existence of the Aspin-Brown Commission on the Roles and Capab ilities of the United States Intelligence Community, and legislation being drafted by the House and Senate committees entrusted with oversight. The goal of the Task Force is to contribute to those efforts and bring about a more informed public debate over the future of U.S. intelligence.

The Council Task Force was comprised of 25 members who met regularly during 1995. A few were professionals, who had direct experience in the world of intelligence. Several were former policymakers, whose roles made them consumers of intelligence. Quite a few members had no direct experience with intelligence but brought to bear insights and lessons from careers in other realms, notably business.

The Task Force did not request access to classified information. As a result, it could not delve into detailed budget questions or specific actions. Nor could it evaluate the past performance of the intelligence community. The Task Force also elected no t to look closely at counterintelligence in light of the several damage assessments and executive and legislative inquiries generated by the Ames scandal.

The Task Force approached this study cognizant that the future of U.S. intelligence is a subject as controversial as it is important. American democracy, with its presumption of openness, has never been comfortable with the unavoidable secrecy of intellig ence and espionage. The legacy of U.S. Secretary of State Henry Stimson, that gentlemen do not read other gentlemen's mail, is still with us.

Moreover, the intelligence community is not without its detractors, both for what it is and what it is not. For some, intelligence agencies are dangerous and prone to scandal, illegality, or both. Others argue the intelligence community lacks competence, citing its failure to predict critical events and its ostensibly lax policing of itself in the Ames scandal and other recent controversies. For still others, the principal question is whether an intelligence community is still necessary in a post-Cold War world in which there is no clear and present danger to U.S. security and in which technology has made information readily available as never before.

The purpose of this effort is straightforward although far from easy: to examine the issues raised in these debates and provide judgments and recommendations about what sort of intelligence capacity this country requires and how the government can best or ganize itself for this purpose.

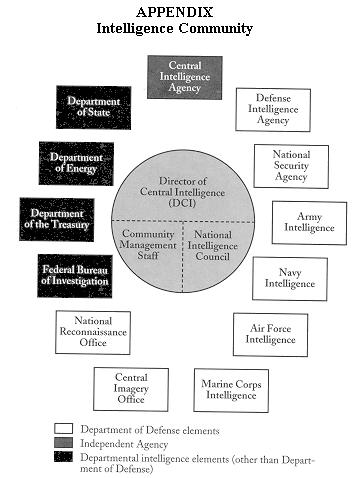

The intelligence community is less a community than a collection of more than a dozen largely autonomous components spread throughout the Washington, D.C. area and the world. The Central Intelligence Agency is but one of these. The others are mostly affil iated with the Department of Defense-the Defense Intelligence Agency, the National Security Agency (NSA), the Central Imagery Office, the National Reconnaissance Office, and the intelligence arms of the four military services-or other government agencies, including the FBI and the Departments of Treasury, Energy, and State. A chart depicting the principal elements of the intelligence community is appended to this report. Loosely overseeing the intelligence community is the Director of Central Intelligence . By law, the individual occupying this post has always worn a second hat, that of Director of the CIA. The DCI is the president's principal adviser on intelligence as well as someone possessing limited ability to affect budgets and programs of the indivi dual intelligence organizations.

The total amount spent each year on intelligence for the U.S. government is classified but has been reported to be approximately $28 billion. The CIA is one of the smaller components, receiving roughly $3 billion or just over ten percent of the resources the United States spends on intelligence. The lion's share of the financial and human resources devoted to intelligence comes under Defense Department programs devoted to intelligence collection in general and support for military operations in particular .

The collection of intelligence can be accomplished in a variety of ways, the most important being the interception of communications and other signals (SIGINT), satellite photography or imagery (IMINT), and reports from human sources (HUMINT). There is al so measurement and signature intelligence, or MASINT, which enhances understanding of physical attributes of intelligence targets. Intelligence analysis reflects conclusions or judgments reached by individuals with access to information from many sources, of which secret information made available by intelligence community collection systems is only part.

Intelligence is not an end in itself Its ultimate purpose is to inform policymakers or military operators. Intelligence can do this in several ways. Intelligence supplements information that is available from open sources (newspapers, speeches, broadcasts ) or diplomatic contacts. The contribution can be raw (a field report, a transcript of a conversation, a photograph) or refined (an analysis from secret as well as open source materials). Indeed, one of the most important functions of various components o f the intelligence community is to provide analysis gleaned from all sources, open and secret, and to package it in a timely and useful manner to policymakers and other U.S. government or even nongovernmental actors.

Covert action is fundamentally different from intelligence collection and analysis. It is intelligence used as an instrument of foreign policy. Such actions seek to influence the political, economic, or military situation in a foreign country without reve aling American involvement in the activity. AS a result, the CIA is divided into several directorates, the two principal ones being for the production of analysis and for conducting clandestine operations, including intelligence collection, counterintelli gence abroad, and covert action.

A number of divergent forecasts of the world to come have been put forward: relative harmony dominated by democracies and market economies, in which the use of military force shrinks as a factor in international relations; rising economic, political, and military competition along the boundaries of major civilizations or cultures; increasing breakdown of order as empires and states implode, protectionism increases, rogue states arm themselves with unconventional weaponry, and/or governments lose control t o criminal gangs or various groups defined by ethnicity, religion, or tribe; or multiple great power competition akin to much of pre-Cold War international relations.

Complicating matters is a lack of consensus over the consequences of these various futures for the United States, that is, how much they would threaten U.S. interests and how much the United States could and should try to affect them. Here again there is a wide range of thinking, from those who advocate a minimalist approach because they discount the importance of most international developments or believe that domestic matters merit the bulk of U.S. attention to those who advocate a more active orientati on in response to necessity, opportunity, or both.

One other development deserves mention as a major influence on the setting for U.S. intelligence: the abundance of information and of communication technologies. Information is now available to policymakers on an immediate ("real time") or nearly immediat e basis through telephones, fax machines, the Internet and other computer links, radio, and television. Accurate and relatively detailed satellite imagery can be purchased. Vast amounts of information are compiled and analyzed by universities, think tanks , and businesses. Transportation improvements make it easier to dispatch someone to get a first-hand impression of a situation with little loss of time. In the military realm, new battle management systems provide combatants with near-instantaneous data o n the disposition of both friendly and hostile forces and targets. The result is that policymakers and other actors now have more information at their disposal-and the intelligence community now has more competitors in providing information to civilian an d military officials and users.

Nor is the need for intelligence eliminated by new sources of information. There are still important but hard to learn facts about targets, including the intentions and capabilities of terrorists and criminal groups, unconventional weapons proliferation e fforts carried out secretly by unfriendly governments, and the disposition of hostile military forces. Such information is rarely available on the "information superhighway" or through commercial satellite imagery; it is certainly not available with enoug h detail and timeliness to serve policymakers and combatants. To the contrary, there are a number of threats to U.S. interests and well-being that can only be identified, monitored, and measured adequately by using dedicated intelligence assets.

This continuing and, in some areas, growing need for intelligence should come as no great surprise. The U.S. government's creation of a modern intelligence capacity predated the Cold War. More than anything else, the desire to avoid another Pearl Harbor l ed to the creation of a centralized intelligence apparatus in 1947. The need to avoid surprise from hostile countries or groups still exists; indeed, the post-Cold War world is one in which the threats to U.S. safety promise to be more in number and type, if less in scale.

Moreover, the utility of intelligence collection and assessment transcends the continuing need to learn about secrets. It also involves the importance of sorting out mysteries, of analyzing events and trends. Indeed, intelligence can often be of greatest use in increasing a policymaker's understanding, rather than in trying to predict individual events. The cadre of analysts maintained by or available to the intelligence community constitutes an important resource for policymakers trying to manage an enor mous stream of information. By default as much as by design, the intelligence community is increasingly the locus within the U.S. government where all sorts of information is integrated and related to policy. If this task were not done by the intelligence community, it would have to be performed elsewhere.

The United States enjoys a position of unique power and, as a result, great opportunity in the post-Cold War world. Intelligence not simply the knowing, but the sharing-is an important tool. Intelligence enables others, be they friendly governments, allia nces, or the International Atomic Energy Agency and other U.N. agencies, to be more effective in dealing with common challenges. Many multilateral efforts will succeed only if the United States possesses and is willing to share the necessary means. Intell igence can be a critical tool in this effort so long as adequate safeguards can be built into the relationships in order to protect classified information and how it was acquired.

The net result of all these considerations is that there is unlikely to be a large budgetary "peace dividend" in the intelligence realm. True, there will always be opportunity for introducing operating efficiencies and reducing redundancies, and there is much less need to monitor and assess developments in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe. But modern systems for intelligence collection are expensive, and the demands on the intelligence community from policymakers and the military to collect and assess information for a wide array of tasks are growing. Accurate intelligence significantly improves the effectiveness of diplomatic and military undertakings; while good intelligence cannot guarantee good policy, poor intelligence frequently contribute s to policy failure. The United States will have to continue to devote significant resources to this area if it wants an enhanced capability.

Intelligence collection priorities, while reflecting both national interests and broader policy priorities, need to be based on other considerations. First, there must be a demonstrated inadequacy of alternative sources; except in rare circumstances, the intelligence community does not need to confirm through intelligence what is already readily available. Second, devoting resources to intelligence can be justified more easily when the efforts of the intelligence community are likely to produce a specific benefit or result for the policymaker or consumer. In short, collection priorities must not only be those subjects that are policy-relevant but also involve information that the intelligence community can best (or uniquely) ascertain.

Throughout most periods of the Cold War, the intelligence community had the responsibility (one might almost say luxury) of focusing the bulk of its resources and efforts on collecting and analyzing information related to the Soviet Union and Eastern Euro pe. This emphasis was both understandable and necessary given the nuclear and conventional military strength of the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies and their ability to threaten the United States and vital U.S. national interests anywhere in the w orld.

In the post-Cold War world, the intelligence community will need to adjust to the reality that the United States faces a less structured world, one in which power in all its forms-economic, political, and military-is more diffuse. It will also have to con tend with a world that not only is more open and transparent than ever but also one that contains large and important areas that remain virtually closed to those dependent on normal means of transportation and communication.

What, then, are the higher priorities likely to be for intelligence collection-but not necessarily for national security policy-in the foreseeable future? We would list the status of nuclear weapons and materials throughout the former Soviet Union; politi cal and military developments in Iraq, Iran, and North Korea; potential terrorism against U.S. targets in the continental United States and overseas; unconventional weapons proliferation; and political-military developments in China. A second category of important but somewhat lower priority intelligence targets would include political developments in Russia and relations between Russia and the former Soviet republics; Mexican stability; the stability of Egypt and Saudi Arabia; Indo-Pakistani relations; d evelopments affecting Middle East peace negotiations; and the activities of international criminal organizations. Political and military developments in Bosnia and the Balkans would necessarily be a high priority if the U.S. military were involved signifi cantly. We would not include on this list such subjects as environmental protection, population growth, or general political and economic developments where open sources are normally sufficient.

The above list (or any such list) is necessarily illustrative, as near-term priorities can change at any moment. Recent experience has shown that unexpected developments in areas of low inherent significance to U.S. national security can suddenly assume c onsiderable but still temporary importance to policymakers. The correct response to such cases is not to expect the intelligence community to be prepared for everything, everywhere. This would waste resources, leave high-priority targets with inadequate c overage, and still not be enough given the unlimited potential for the unexpected. Instead, the president and the DCI should consider creating a formal intelligence reserve corps for dealing with so-called "pop-up" issues. Such a corps could consist of fo rmer intelligence professionals, academics, and others with particular geographic and functional expertise. Working with a point of contact in the intelligence community, they would be asked to collect data, provide reports, and be available to work full time if a crisis suddenly developed in their area and if their expertise were required.

Still, it is worth making an effort to overhaul the process by which requirements and priorities are established. The resources involved are considerable, and there is an opportunity cost in the sense that the intelligence community chooses to cover or is directed to cover some targets at the expense of collecting information about others. Currently, the staff of the National Security Council (NSC) oversees an interagency process that annually lists priorities that are too numerous to be meaningful. Moreo ver, the reality is that few senior policymakers in years past have participated in such formal efforts. As a result, intelligence requirements are most often set by intelligence producers or by relatively junior officials in the policymaking departments.

It should be possible to empower a committee composed of mid-level officials (or aides to senior officials) from the intelligence and policymaking communities to convene regularly to determine and revise priorities. The key is to try to get policymakers t o provide guidance for both collection and analysis, to communicate not just what they want but also what they do not. The intelligence community ought not be an all-purpose source of information for either the executive branch or Congress. Individual age ncies and departments should fulfill their own general information needs, either by developing an in-house capability or by exploiting what is available in the private sector.

Some market constraint, under which consumers can only receive so much free intelligence before their own agency has to find resources to support a greater intelligence effort, could be introduced. Alternatively, new requirements for intelligence could be added only if the requesting agency specifies what existing requirements it is willing to forego. The intelligence community ought to retain the ability and reserve resources to provide information and analysis in areas that it believes are or should be- or could be important to policymakers even when the latter have yet to articulate such a need.

It is important that intelligence officers involved in articulating requirements represent both analysts and collectors, including those from the clandestine side. In addition, collection should be affected by the needs of policymakers and operators. All of this argues strongly against any organizational reforms that would isolate the collection agencies further or increase their autonomy.

The best way to ensure high-quality analysis is to bring high quality analysts into the process. Here it helps to think of the challenge as one of improving both the stock and the flow of personnel. Certain stock (career personnel) need to be encouraged t o specialize in a geographical area or function and rewarded for excellence. Not everyone need pursue a career with a management component. This is not meant to diminish the value of management skills. To the contrary, the CIA in particular needs to place much more emphasis on formal management and leadership training as well as demonstrated competence as a prerequisite for promotion for those headed for senior levels.

But better analysis will also require reducing the isolation of the intelligence community. A greater flow of talented people into the agency from academia and business is essential. Greater provision ought to be made for lateral and mid-career entry as w ell as for short-term entry (measured in weeks, months, or years) or even for just a single, short-duration project. In this way the intelligence community could attract and exploit some of the best minds from academia and other sections of society that w ould otherwise not be available.

Working to improve the quality of analysts, however, is not enough; it is also necessary to change the relationship between intelligence producers and consumers. Intelligence professionals must understand the needs of policymakers and vice versa. One way to do so is through regular rotation of career intelligence officers into positions in the policymaking departments (State, Defense, Treasury, etc.) and the NSC. Temporary assignment to the relevant congressional staffs should also be an option. Sabbatica ls in academia or business would be similarly useful; indeed, such rotations should be required for promotion to senior levels. The same logic argues for assigning careerists normally in the policymaking realm to periodic tours inside the intelligence com munity.

The danger of politicization-the potential for the intelligence community to distort information or judgment in order to please political authorities-is real. Moreover, the danger can never be eliminated if intelligence analysts are involved, as they must be, in the policy process. The challenge is to develop reasonable safeguards while permitting intelligence producers and policymaking consumers to interact.

The need to protect intelligence from political pressure and parochialism is a powerful argument for maintaining a strong, centralized capability and not leaving decisions affecting important intelligence-related questions solely to the policymaking depar tments. (Centralization raises the risk of politicization stemming from the DCI. Only the president, senior officials involved in national security, and Congress can help guard against politicization-though they too can try to politicize intelligence.) Un like business, the customer is not always right. Decentralization of analysis should be limited to questions with little or no impact beyond the agency in question.

The intelligence community can protect itself from political pressure through competitive analysis of controversial questions. Guarding against politicization is also a useful function for Congress and the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board. (One option to consider in this regard would be to reconstitute the PFIAB to make it selected by and responsible to Congress as well as the president, as was the Aspin-Brown Commission.) Perhaps most important, the leadership of the intelligence community should reinforce the ethic that speaking the truth to those in power is required-and defend anyone who comes under criticism for doing so.

Irrelevance is a related and arguably bigger problem for analysts than politicization. Intelligence analysis rarely impresses itself upon policymakers, who are inevitably busy and inundated with more demands on their time and attention than they can possi bly meet. Intelligence officials must draw attention to their product and market their ideas. This is especially true in the case of any early-warning or intelligence-related development that has potentially significant consequences for important interest s. A phone call, a personalized memorandum, a meeting-any and all are required if the situation is sufficiently serious. Involving relevant policymakers and other consumers in the regular personnel evaluations of the analysts who serve them would underlin e the importance of such an effort and provide an incentive to individual analysts.

Another serious problem to be avoided is mindset or "groupthink." Any organization, and the CIA or any intelligence agency is no exception, can fall into the trap of not questioning basic assumptions that affect much subsequent analysis. It is essential t hat competitive or redundant analysis be encouraged. Currently and historically, less than a tenth of what the United States spends on intelligence is devoted to analysis; it is the least expensive dimension of intelligence. Not all duplication is wastefu l. This country could surely afford to spend more in those areas of analysis where being wrong can have major adverse consequences.

One other aspect of analysis merits mention, namely, the balance between current intelligence and long-term estimates. For years the culture of the intelligence community, in particular that of the CIA, has favored the latter. But it is precisely in long- term analysis of familiar subjects and broad trends where secret information tends to be less critical and government analysts are for the most part no better and often not as good as their counterparts in academia and the private sector. Also, many estim ates are likely to be less relevant to busy policymakers, who must focus on the immediate. All this suggests that the emphasis placed on such estimates should be reduced. To the extent long-term estimates are produced, they ought to be concise, written by individuals, and sources justifying conclusions ought to be shown as they would in any academic work. If the project is a group effort, differences among participants ought to be sharpened and prominently acknowledged. While it is valuable to point out a reas of consensus, it is more important that areas of dispute be highlighted than that all agencies be pressured to reach a conclusion that represents little more than a lowest common denominator.

Collection of secret economic information can be by several means-mostly SIGINT and HUMINT, in rare cases through imagery-and involve such questions as trade policy, foreign exchange reserves, the availability of natural resources and agricultural commodi ties, money laundering, and virtually any aspect of another country's economic policy and practices and those of its major corporations. Analysis can be used to support specific negotiations and to understand better what might be termed strategic or polit ical-economic trends involving emerging technologies, markets, or the policies of major economic actors.

There is no need for the intelligence community to replicate what is already done by the private sector or other government agencies in the accumulation of statistics and other forms of basic information. Such collection (in effect, collation) can be bett er carried out by one of the relevant agencies, particularly Commerce and Treasury. In some instances, the information or expertise can simply be purchased.

Economic intelligence should not be used offensively, that is, to help a particular U.S. firm with a narrow commercial purpose, such as winning a contract against foreign competition. This is not a proper use of public resources, especially for a market-o riented country like the United States. Such activity could seriously strain relations with our principal trading partners, and it would be difficult, if not impossible, to implement if more than one U.S. firm were involved. There is another consideration , namely, the question of what constitutes an American firm nowadays. But it is appropriate for intelligence to be used defensively so that policymakers can act if bribes or other unfair practices are being used against an American firm. Leveling the pl aying field is acceptable; tilting it is not. Counterintelligence assets should also be used to help protect U.S. firms from the espionage efforts of foreign firms and governments.

Most Task Force members agreed with the points just noted. Consensus proved elusive over the priority to accord economic intelligence and over the degree of risk and the amount of resources its collection and analysis warranted. Several members believed t hat collection of intelligence for economic purposes can easily cause more problems with America's major trading partners (including Canada, Mexico, Japan, and Germany) than it purports to solve. In their view, this suggests the need for caution in collec ting intelligence, especially HUMINT, for economic purposes. Many members of the Task Force, however, believed that such collection is accepted practice among states and the political costs of being discovered are worth bearing given the importance of eco nomic issues and the potential value of the information for policymakers.

A second area of disagreement concerned both collection and analysis and the degree to which the intelligence community should focus on long-term or strategic issues. Many members of the Task Force felt strongly that this was a priority. Examples cited we re the economic health of a country such as Mexico, where economic failure would not only have major financial consequences for the United States but also could trigger a wave of emigration; the economic situation in Russia or China; and the long-term eco nomic direction of such major partners and competitors as Japan, the Republic of Korea, India, and the European Union. Other members of the Task Force argued that while those were important questions, the U.S. government would do better to rely mostly on open sources in the academic world and the private sector. In their view, the intelligence community has little or no comparative advantage in undertaking such assessments and should focus its collection and analysis on making unique and needed contributi ons.

A second task for the clandestine services is covert action, that is, the carrying out of operations to influence events in another country in which it is deemed important to hide the hand of the U.S. government. Historically, covert action has included s uch activities as channeling funds to selected individuals, movements or political parties, media placements, broadcasting, and paramilitary support. Such operations can be designed to bolster the capabilities of friendly governments in dealing with chall enges to them and their societies. Covert measures can also have the opposite purpose, to weaken a hostile government. The capability to undertake these and other tasks-be it to frustrate a terrorist action, intercept some technology or equipment that wou ld help a rogue state or group build a nuclear device, or assist some group trying to overthrow a leadership whose actions threaten U.S. interests-constitutes an important national security tool, one that can provide policymakers a valuable alternative or complement to other policies, including diplomacy, sanctions, and military intervention.

Clandestine operations, whether for collection of foreign intelligence, counterintelligence, or covert action, will often require associating with individuals of unsavory reputations who in some instances may have committed crimes. This differs little fro m the tradition in law enforcement of using criminals to catch criminals and should be acceptable so long as the likely benefits outweigh the certain moral and potential political costs of the association-a calculation that should not be made solely by th e person in the field. The only other word of caution the Task Force noted (in addition to ensuring legality, sufficient control, and adequate oversight) is that any covert action must appear consistent with established U.S. policy so that, if discovered, the purposes behind the effort would be understood.

Clandestine operations for whatever purpose currently are circumscribed by a number of legal and policy constraints. These deserve review to avoid diminishing the potential contribution of this instrument. At a minimum, the Task Force recommended that a f resh look be taken at limits on the use of nonofficial "covers" for hiding and protecting those involved in clandestine activities. In addition, rules that can prohibit preemptive attacks on terrorists or support for individuals hoping to bring about a re gime change in a hostile country need to be assessed periodically.

Maintaining and enhancing clandestine capabilities takes time and resources; creating and nurturing such capabilities ought to be a high priority of the intelligence community given the importance of targets that otherwise cannot be reached. Individuals m ust not only learn the craft but also develop language skills, deep knowledge of a society, and covers to shield their intelligence-related activity. They will also benefit from having available an adequate official U.S. presence; the closing of U.S. emba ssies and other missions abroad reduces the capacity to collect intelligence and undertake clandestine operations.

On the other hand, one cannot ignore the Directorate of Operations' record of operating with questionable legality and judgment. Constant vigilance inside the CIA is needed to ensure that the DO is doing quality work consistent with policy priorities, sen ior officials inside and outside the CIA are kept fully informed, officer's actions are consistent with existing regulations and laws, senior DO personnel are treating their employees responsibly, and analysts outside the directorate have full access to i ts product. In return, those in the operations directorate should know that risk-taking will be supported and they will be politically protected so long as what they do is authorized and legal under U.S. law at the time. Such support is crucial; contrary to widespread impressions, one problem with the clandestine services has been a lack of initiative brought about by a fear of retroactive discipline and a lack of high-level support. This must be rectified if the intelligence community is to continue to p roduce the human intelligence that will surely be needed in the future.

The relationship between the DCI and the heads of the various intelligence agencies (NSA, DIA, and so on) is a critical issue. At stake are not simply questions of organization and procedure but the control of resources, personnel, and policy. Currently, priorities are largely determined by component agencies. Overall or national priorities are set mostly by the Defense Department. Not only does the military receive the lion's share of intelligence resources, but the military services and the leadership o f the Defense Department programs, which include the large and expensive technological collection efforts, are the most powerful voices when it comes to deciding what systems are to be built. Not surprisingly, this biases both how and where resources are spent and what the resulting infrastructure is used for.

One approach to reform would further decentralize U.S. intelligence by reducing the already constrained ability of the DCI to determine where resources are spent and influence the heads of the component intelligence agencies. Even more significant would b e a decision to decentralize intelligence analysis and leave each policymaking department to conduct its own analysis. There is some appeal to this because it could strengthen the ties between intelligence producers and consumers. This would be acceptable and even desirable in narrow, often technical, matters of concern only to the agency in question, such as is the case when the intelligence organizations of the military services assess a potential adversary's new equipment or tactics. But on matters that involve more than one agency, are national, or involve choices in collection assets or targets for coverage or analys is, decentralization is normally a liability. What is required is a national perspective that in turn requires either a large central agency or an individual (the DCI or another figure) with the ability to make decisions affecting all community members. D ecentralization (and full-time pairing of intelligence and policymaker) in these areas could easily lead to politicized assessments and decisions that reflect parochial concerns. Busy policymakers who depend on coordinated views and who do not normally ha ve time to deal with multiple assessments of the same problem would encounter more difficulty.

This conclusion argues for change in the current design of intelligence but a change that would bring about greater centralization. There are two paths to strengthening the center at the expense of the periphery. One would be to create an intelligence cza r or Director of National Intelligence (DNI). This person would have clear authority over the heads of the other intelligence agencies, making him first among unequals. In so doing, it would be necessary to separate the two functions now carried out by th e DCI and create a separate Director of the CIA.

The advantage of this approach, which was supported by several members of the Task Force, is that it would create one person with a community-wide perspective and the ability to determine which systems and issues received priority. The intelligence commun ity would, at least in principle, be more responsive to change. But such a change would work only if the DNI were given complete authority over the entire intelligence program, a large staff to oversee the components, and the power to control budgets. Oth erwise, he would be a general with no troops, too weak to rein in the large agencies supposedly under his control. (The unsuccessful experience of the so-called drug czar comes to mind here.) Also, such a reform would certainly trigger great political and bureaucratic resistance; any president would have to think hard before setting off on such a course and dealing with resistance from the CIA and Congress. This reform could also bring about regular clashes between the DNI and the national security advise r, whose role already includes elements of the proposed DNI's mission.

A second alternative would be to bolster the strength of the DCI in the current context, that is, with his two hats. The DCI could be given the right to nominate and reject nominations to head the other agencies and/or he could be given authority to deter mine budgets and be able to move people and resources to respond to changing circumstances. The result, in practice, would be a DCI similar to what was planned a half-century ago.

In some ways, this reform would be analogous to reforms introduced several years ago in the defense area. There, the Goldwater-Nichols Act strengthened the hand of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff at the expense of the secretaries of the military services. The result has been to make it less difficult to plan and execute joint (multiservice) operations. The advantage of this approach (besides those already presented in making the case for a DNI) is that it involves little structural change and would give one person greater control over the community. The DCI already has in place many of the resources needed to take on this larger burden.

But this option, too, is not without drawbacks, many of which mimic the potential problems with establishing a DNI. Any centralization of authority brings with it the danger of making bigger mistakes. Moreover, power over the appointment of top personnel could easily result in a forced consensus and politicization. Also, it asks a great deal of one person to be both a player and a referee, and there is the danger that the DCI will inevitably favor the interests of the CIA if he remains responsible for it as well.

Despite these potential drawbacks, a majority of the Task Force favored creating a stronger DCI. Such centralization promises to be the best way to bring about high-quality, coordinated analysis, to reduce redundancies, and to make resource decisions that reflect national priorities-and resist pressures from those who oversee the technical collection programs or who are concerned with military programs alone. The Task Force believed that the dangers of such a reform could be offset by establishing an appe als mechanism involving senior officials that could review serious disagreements over budget and policy. Moreover, the Task Force believed that the danger of a stronger DCI politicizing analysis could be reduced by the NSC carrying out the oversight respo nsibility it already holds in this realm.

There are a number of lesser but still important organizational issues worth raising. The first is the tenure of the DCI. There is an argument for appointing the head of the CIA for a fixed and arguably lengthy term to increase the odds he will be able to provide independent and knowledgeable advice. On balance, though, the need for a president to respect and feel comfortable on a personal basis with his principal intelligence adviser is even more important. Without that, there is a risk that intelligence will be ignored. The head of intelligence ought to serve at the pleasure of the president. (This is not intended as a call for new presidents to replace the incumbent DCI, only as a note that the option exists.) Accountability will be promoted by congres sional oversight and public estimates of competence. The Task Force did not believe questions of rank or formal membership in the NSC system to be important; what matters is access to the president and the other principals involved in national security.

Nevertheless, the Task Force was concerned about the influence over intelligence policy exerted by the Defense Department and defense-related concerns. There is a danger that spending on intelligence to support military operations will take priority over other important or even vital national security ends in which intelligence is needed. There is the related concern that the voice of the Defense Department will grow too strong, something which reflects the organizational reality that the Defense Departme nt manages the large collection programs that consume a significant share of the resources dedicated to intelligence. It is one thing for the bulk of intelligence effort to be dedicated to supporting military operations; it is quite another for the Depart ment of Defense to have a dominant voice in determining that allocation. For this reason, while the Task Force was inclined for reasons of efficiency to support the consolidation of imagery and mapping functions in a single agency, it questioned the desir ability of locating this new organization within the Defense Department.

The Task Force also questioned the way the intelligence operations of the Defense Department are organized. Currently, no one directs all military intelligence. As a result, some people favored creating a Director of Military Intelligence (DMI), who if pr operly staffed would assign missions among the armed services, various commands, the JCS, and the Defense Intelligence Agency. One way to bring this about would be to give the director of DIA a second hat, which could help him determine a better division of labor between existing and planned national intelligence assets managed by the Department of Defense and defense programs that provide intelligence, such as unmanned vehicles. Such defense systems hold the potential to provide intelligence directly to commanders, thereby relieving national intelligence assets of this requirement.

There are, however, risks in consolidating further control over defense intelligence. Concentrating authority in DIA would conflict with the Goldwater-Nichols reforms that increased the role of the intelligence arm of the JCS and the commanders in the fie ld. An alternative that takes this last consideration into account would make the intelligence chief of the Joint Chiefs of Staff-the J-2-the head of military intelligence. But such a reform might bring too much centralization for such a far-flung organiz ation. Moreover, any centralization of defense intelligence and power would make it easier for the Defense Department to promote its own interests and further frustrate the efforts of the DCI to make national decisions.

The Task Force did not have a strong preference on the utility of establishing a DMI. More pressing in its view is the need for a clear division of labor so that redundancies in the Department of Defense are avoided. The Task Force questioned the necessit y and desirability of maintaining large service intelligence capabilities. The services are charged with equipping and training their personnel, and any intelligence not tied to specific service missions ought to be eliminated or located elsewhere. Ration alizing defense-related intelligence and the roles of the military services, the JCS, DIA, field commanders, and the office of the secretary of Defense is a task that a stronger DCI or the secretary of Defense should undertake as an urgent priority.

A number of other non-organizational changes also seem desirable. Defense intelligence should focus on more narrow questions of defense capabilities and targets and leave more political questions (as well as the collection of human intelligence) to others . Greater use could be made of reserves for crises in low priority areas. Last, the Defense Department needs to continue to place greater emphasis on dissemination of intelligence to the operators of weapons systems. All the collection and analysis in the world helps little if it is not in the hands of those who need it, on time and in a useful form.

As a rule of thumb, foreign policy ought to take precedence over law enforcement when it comes to overseas operations. The bulk of U.S. intelligence efforts overseas is devoted to traditional national security concerns; as a result, law enforcement must o rdinarily be a secondary concern. FBI and DEA agents operating abroad should not be allowed to act independently of either the ambassador or the CIA lest pursuit of evidence or individuals for prosecution cause major foreign policy problems or complicate ongoing intelligence and diplomatic activities. (The same should hold for any Defense Department personnel involved in intelligence activity overseas.) There are likely to be exceptions, and a degree of case-by-case decision-making will be inevitable. Wha t is needed most is a Washington-based interagency mechanism involving officials from intelligence, law enforcement, and foreign policy to sort out individual cases. One now exists; the challenge is to make it work.

At home, law enforcement should have priority and the intelligence community should continue to face restraints in what it can do vis-a-vis American citizens. Certain rules that are in effect to protect civil liberties continue to make sense. The prohibit ion against the CIA deliberately collecting information inside the United States or overseas on U.S. citizens for law enforcement purposes should be maintained except where there is a formal requirement-in cases of counterintelligence or drug trafficking- or a court order. Regardless, the ability of intelligence agencies to give law enforcement incidentally acquired information on U.S. citizens at home or overseas ought to be continued. There should be no prohibition (other than those based on policy) on t he intelligence community collecting information against foreign persons or entities. The question of what to do with the information, however, should be put before policymakers if it raises foreign policy concerns. More generally, the complex subject of relations between intelligence and law enforcement agencies is a good candidate for additional review and reform.

At the same time, congressional oversight is costly in several ways. It often places a cumbersome demand on senior intelligence officials and requires a great deal of time spent testifying and briefing. Although formal oversight is restricted to the House and Senate select committees, both appropriations committees are involved in budgetary review, and several other committees, including both foreign affairs and defense committees, regularly request and receive briefings. The Task Force suggested that Con gress consider merging the select committees and others for selected briefings and hearings. A single, joint oversight committee would not be advisable as it would place too much power in the hands of one small body. The Task Force also suggested that the limits on how long an individual member is allowed to serve on an intelligence committee be removed so as to increase congressional expertise. One way to accomplish this would be to convert the Senate and House select committees into permanent committees with non-rotating membership.

Current practice on covert action appears sound. As things now stand, the executive branch must inform the oversight committees or, in special cases, a smaller circle of congressional leaders of any such action in advance or in a timely fashion and in wri ting. Such consultations provide the Congress with an opportunity to discourage (but not prevent) the administration from undertaking a proposed course of action. The Task Force believed that such an informal consultative approach, rather than a requireme nt for a formal authorization or a formal constraint, works best. The initiative should remain with the executive in this area.

One particular question that requires consideration is the openness of the intelligence community's budget. The annual request for intelligence is hidden in various accounts, largely defense. Moreover, the overall size of the budget is classified. In the view of the Task Force, this number could be made available, as could basic elements of the intelligence program. A problem will come with the degree of detail provided. As is the case with the defense budget, large areas of spending will need to remain c lassified to protect sensitive undertakings and so as not to discourage other intelligence services from working with the United States.

The current opportunity for reform of the intelligence community must not be squandered or distorted. As this report makes clear, the intelligence community does much that is good; there is also much it can and should do better. The president, working wit h the bipartisan leadership of Congress, ought to create a steering group chaired by the vice president and comprised of senior administration officials-say, the DCI, the national security adviser, and the deputy secretaries of State and Defense-the chair men and ranking members of the two select committees, and representatives of both the Aspin-Brown Commission and the PFIAB to oversee necessary reforms and new legislation. If this report has one overriding message, it is that intelligence is a critical r esource and tool and its maintenance and improvement ought to be a national priority.

Regarding estimates, it is all too true that many of them appear useless to policymakers, and much can and should be done to improve them. But the solution is not to downgrade them further, as the report recommends; the priority of estimates relative to c urrent intelligence analysis has already declined since the first 30 years of the Cold War. Even when they do not seem to offer new information, formally coordinated estimates perform important functions that would be undermined by the report's recommenda tion.

Bureaucratization of the estimating process is the source of its problems, but also of its value. In contrast to single agency analyses, estimates compel disparate elements of the intelligence community to confront each others' arguments and sharpen the d etermination of what judgments are based on evidence as opposed to tradition, intuition, or ideological bias. This discipline does not always work, but at least occasionally it can force questions to the surface and challenge unexamined assumptions. Witho ut such exercises it would be much easier for the secretary of State to rely uncritically on his own INR, the secretary of Defense on DIA, the White House on CIA, or for policymakers anywhere to pick and choose among whichever analyses echoed their prejud ices. If the problem is that coordinated estimates tend to reduce analysis to mushy common denominators that waste policymakers' time, the solution is not to reduce estimates but to reconfigure them (for example, highlighting key disagreements and unknown s as much as agreed conclusions).

In forcing a collective judgment about evidence, estimates establish a baseline for the burden of proof in policymaking. If assumptions of a policy contradict conclusions of an estimate, policymakers should at least have an explicit rationale for why. Int elligence professionals see too often how policymakers ignore estimates they consider unhelpful, only to find later how much they should have heeded them. The most tragic example is the long record of estimates on Vietnam, most of which pointed to why U.S . strategy would not succeed, and which were ignored by the administrations that moved deeper into the disaster.

When the report notes that estimates may be irrelevant to policymakers who must focus on immediate problems, it notes a problem in policy more than analysis. Policymakers' inability to think seriously beyond pressing current problems is chronic, for under standable reasons, but it leaves them vulnerable to bigger problems that grow while they are preoccupied. It does not hurt to "waste" a few resources on estimates that tug at their sleeves and remind them that tomorrow's potential crisis may make today's actual crisis seem trivial. One of the most important functions of intelligence is not to ease the job of policymakers but to complicate it, to tell them things they do not want to hear.

On congressional oversight, the report's language implies that it is a burden except when the committees collaborate supportively with the executive. This is a common view among technocrats but it misses the essence of American government: the priority of checks and balances enshrined in the constitution. James Madison was not out to design a system to make policymaking efficient, but to create one that would constrain power. If this was a mistake, it bears on intelligence no more than on any other matter of public policy. There is no obvious reason that the executive should be less constrained on intelligence than on other aspects of foreign affairs or government administration, especially when safeguards for secrecy have been as carefully cultivated as they have been with the intelligence committees. (These committees have proved far more responsible about protecting classified information than have White House staff, the policy departments of the executive branch, or other committees of Congress.)

Indeed, the centrality of secrecy is an obvious reason why oversight of intelligence should be even more thorough than on other subjects. On most normal matters of public policy, voters, the press, and Congress as a whole can debate and second-guess admin

istration policy in a reasonably informed way. As long as official secrecy holds, this is not possible on intelligence. If checks on intelligence policy are not to depend on rumors, myths, or leaks, the public and Congress as a whole must in effect deputi

ze the intelligence committees to do the job for them. When the executive resists or subverts the oversight of the intelligence committees (as happened on matters like the mining of Nicaraguan harbors and the sale of arms to Iran), it damages public suppo

rt for official secrecy and thus undermines intelligence. If a political consensus for maintaining strong intelligence capabilities is to be preserved, cooperation between Congress and the executive is indeed important, but not simply on terms that are co

nvenient for one of the two branches.

Richard K. Betts

In prescribing organizational remedies for what ails our intelligence apparatus, we should draw a distinction between further consolidation and further centralization. More consolidation-determining who will do what and eliminating duplication of effort-i s probably worthwhile. Some evidence for this view can be found in the Task Force report. The case for more centralization-including the shift of responsibility and authority toward the center and up-is harder to make. We ought to be skeptical about this approach, in part because we have so much experience with failure of highly centralized organizations. The collapse of the Soviet Union, for instance, provides lots of nearly contemporaneous evidence. But there is no shortage of confirmation in the recent track record of American industry. Notwithstanding this testimony, the Task Force report recommends that greatly increased clout be given to the DCI, including "hire and fire" authority over intelligence officers and substantially greater say in intellig ence budgets.

The common sense approach is to strengthen, where possible, the tie between authority over resources ("inputs") and responsibility for results ("outputs"). Accordingly, increased centralization may be appropriate in those cases where intelligence is itsel f the desired output or where ensuing action takes place inside the intelligence context, e.g., covert action. At least in theory, there can be the requirement simply to possess information in order to better understand the situation, without any subseque nt action. Intelligence is already centralized enough to take care of such cases.

However, the more usual rationale for acquiring intelligence is that it forms the basis for action. The illustrative case is military operations, where intelligence-information about present and potential threats-is understandably critical in determining battle outcomes.

We rightly hold the secretary of Defense and his subordinate field commanders responsible for the success or failure of military operations. It follows that they should be given very great authority over factors determining success or failure. Such author

ity will never be absolute, given our system of government and its distribution of power. But the "mistake" we want to make is to give those who have bottom line responsibility a shade too much authority.

General Merrill A. McPeak

Although the Task Force report discusses the growing influence of defense officials in shaping U.S. intelligence policy, we believe the report does not sufficiently highlight how far this trend has gone. That this is even an issue is ironic. During the Co ld War, when U.S. military forces were engaged in matters of national survival, there was a reasonable balance between civilian and military players both in the intelligence and policy arenas. Threats from the Soviet military arsenal were assessed by stro ng scientific and technical centers at the national laboratories and at the CIA as well as by the military services and DIA. The National Reconnaissance Office was under strong civilian influence and many of the national strategic intelligence programs we re developed and operated by civilians. The policy process that addressed the Soviet military threat and crises anywhere in the world was led by the State Department and the NSC. The JCS and the office of the secretary of Defense were strong but not domin ant players. Most important, the civilian side of U.S. intelligence had a major role in allocating resources for national intelligence. Parochialism was for the most part contained.

Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. military has increasingly dominated the intelligence process. The watchword today in the intelligence community is support to military operations. The emphasis is on current crises and the short term, in part becaus e military intervention has become a more frequently used tool of foreign policy. For all practical purposes, the control of technical intelligence collection has been passed to the Department of Defense. A weakened CIA-the major civilian player-plays a l esser role in the national security process and spends more and more of its resources to support military operations in a world where political, economic, and social issues present an increasingly important challenge but get much less attention. Because s o much authority for national intelligence programs is moving toward Defense, the control of resources and the determination of collection and analytic priorities has moved in that direction as well. While much lip service is paid to the needs of top fore ign policy and national security officials there has been less attention and fewer resources devoted to meeting their needs. The national intelligence budget process has been subsumed by Defense. We believe this trend needs to be checked and a better bala nce struck between civilian and military participation and in how intelligence funds are spent.

Morton I. Abramowitz

Richard Kerr

From time to time, the Council will select a topic of critical importance to U.S. policy to be the subject of close study by an independent, nonpartisan Task Force. The Council then will appoint a chairman and with the chairman choose a Task Force represe nting diverse views and backgrounds and including generalists as well as experts. Most, but not all, Task Force members are also members of the Council, and the Council provides the group with staff support.

The Council on Foreign Relations takes no position on issues. The Task Force takes responsibility for the content of its report. The report reflects the general policy thrust and judgments reached by the group, although not all members of the group necess arily subscribe to every finding and recommendation in the report. Institutional affiliations listed in the Members of the Task Force are for identification purposes only.

For further information about the Council or this Task Force, please contact the Public Affairs Office, Council on Foreign Relations, 58 East 68th Street. New York, NY 10021.

Copyright 1996 by the Council on Foreign Relations, Inc. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. The report may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Special thanks are due to Mary E. Richards, who served as rapporteur for the meetings of the Task Force and oversaw all administrative arrangements.

The chairman and director of the Task Force wish to acknowledge the John M. Olin Foundation, Inc., whose support of the national security program at the Council on Foreign Relations helped underwrite this effort.

RICHARD K. BETTS: Mr. Betts is Professor of Political Science and Director of the International Security Policy Program in the School of International and Public Affairs at Columbia University.

PAUL BRACKEN: Mr. Bracken is Professor of Management and of Political Science at Yale University. He also serves on the Chief of Naval Operations Executive Panel and on the Army Science Board.

CHESTER A. CROCKER: Mr. Crockeris Research Professorof Diplomacy at Georgetown University. He also serves as Chairman of the Board of the United States Institute of Peace and was formerly Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs.

JAMES H. EVANS: Mr. Evans is former Chairman and CEO of Union Pacific Corporation. He has also served as President and a Director of Union Pacific and as President and Chair man of the Seamen's Bank for Saving.

LESLIE H. GELB: Mr. Gelb is President of the Council on Foreign Relations. He was a foreign affairs columnist and Editor of the Op-Ed page for The New York Times. He also served as Director of the State Department's Bureau of Politico-Military Affairs.

PAUL E. GRAY: Mr.GrayisChairmanoftheCorporationfor Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Previously, he served as MIT's President and as Chancellor of the Institute.

MAURICE R. GREENBERG: Mr. Greenberg is Chairman and CEO of American International Group, Inc.

HENRY A. GRUNWALD: Mr. Grunwald is former Editor-in Chief of Time, Inc.

RICHARD N. HAASS: Mr. Haass is Director of National Security Programs and Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations. He served as Special Assistant to President George Bush and Senior Director for Near East and South Asian Affairs of the National Security Council.

WILLIAM HOOD: Mr. Hood is a former Executive Off1cer of the Counterintelligence Staff of the CIA.

CORDELL HULL: Mr. Hull is Executive Vice Chairman of Bechtel Enterprises, Inc.

RICHARD KERR: Mr. Kerr is former Deputy Director of the CIA and Deputy Director of Central Intelligence. He also served as Acting Director of Central Intelligence.

JOSHUA LEDERBERG: Mr. Lederberg is University Professor and President Emeritus as well as Sackler Foundation Scholar at The Rockefeller University.

JESSICA T. MATHEWS: Ms. Mathews is Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations and a columnist for The Washington Post. She served as Deputy to the Under Secretary of State for Global Affairs and was Vice President of the World Resources Institute.

MERRILL A. MCPEAK: General McPeak (U.S. Air Force, retired) is President of McPeak and Associates. He was formerly Chief of Staff of the U.S. Air Force.

LIONEL OLMER: Mr. Olmer is a partner in the law firm of Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison. He was formerly Under Secretary of Commerce for International Trade.

EDWIN J. PECHOUS: Mr. Pechous is an independent consul tant and recently retired senior U.S. government official who spent much of his career with the CIA.

JAMES D. ROBINSON III: Mr. Robinson is President of J. D. Robinson, Inc. He was formerly Chairman and CEO of American Express.

BRENT SCOWCROFT: General Scowcroft (U.S. Air Force, retired) is President of the Forum for International Policy and the Scowcroft Group. He was National Security Adviser for Presidents George Bush and Gerald Ford.

ANGELA E. STENT: Ms. Stent is Professor of Government at Georgetown University.

GORDON RUSSELL SULLIVAN: General Sullivan (U.S. Army, retired is Corporate Vice President of Coleman Research Corporation. He was formerly Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army.

ROBERT C. WAGGONER: Mr. Waggoner is President of Burrelle's Information Services. He is also Chairman of Video Monitoring Services of America, Inc.

JOHN L. WEINBERG: Mr. Weinberg is Senior Chairman of Goldman Sachs & Company.

FRANK G. ZARB: Mr.Zarbis President and CEO of Alexander and Alexander Services, Inc. He has served as Vice Chairman and Group Chief Executive of the Travelers Inc. and as Chairman and CEO of Smith Barney.

CHARLES BATTAGLIA: Mr. Battaglia is Majority Staff Director for the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence. He worked for the CIA in the early 1980S.

MARK LOWENTHAL: Mr. Lowenthal is Staff Director for the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence. He has served as a senior analyst at the Congressional Research Service and in the State Department's Bureau of Intelligence and Research.

BRITT SNIDER: Mr. Snider is Staff Director of the Commission on the Roles and Capabilities of the United States Intelligence Community.